When it comes to the law of unintended consequences, there is now the case of a law, originally intended to encourage the use of Michigan farm products within the state’s distilleries and brewpubs, unexpectedly transforming the Wolverine State into a creative epicenter for liquors.

Pride, determination and a desire to create something unique are a few of the things to be found in craft cocktail culture in Michigan. If you happen to be sipping the likes of a Bijou, Admiral, Rusty Nail or any other cocktail at a Michigan distillery, the components of your libation may likely be made entirely from in-house ingredients. In accordance with Michigan state law, if a distillery operating a tasting room chooses to serve cocktails, all mixers (except the non-alcoholic ones and bitters) must be made on premise using in-house spirits.

Whereas, this level of regulation may seem draconian, most craft distillers in the state take a positive approach and choose to see the law not as a barrier, but as an opportunity to create a superior cocktail experience.

“It was very difficult early on,” said Rich Blair, National Accounts Manager for New Holland Brewing and Distilling. “But now we control, to a very high degree, everything that goes into the glass. We’re not leaning on anyone else. We have embraced it.”

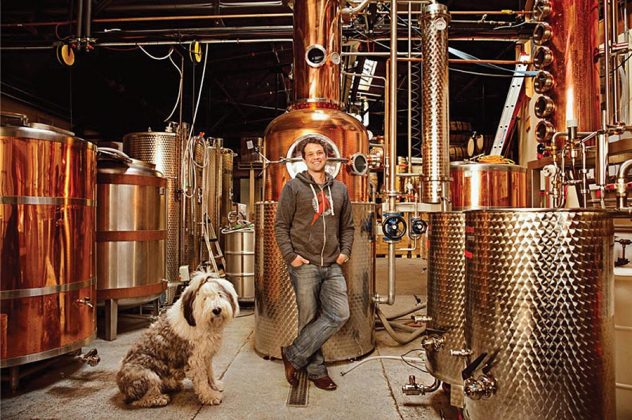

New Holland, located in the college town of Holland, on Michigan’s west coast, is known around the Great Lakes region as a pioneer of Midwestern spirits. Originally opened in 1996 as a brewpub, the company was instrumental in lobbying the state to change distilling law to allow the use grains and canes to make spirits.

“Until 2008, everything had to be distilled from fruits, so everything had to be a brandy or eau de vie. When that law was struck down, we could begin distilling rum from molasses and cane sugar, and whiskey from grain,” Blair said.

The impulse behind the effort to push this change was spurred in part by co-founder Brett VanderKamp’s desire to begin distilling, following a life-changing surfing trip. “Brett tells a story,” said Blair. “He was surfing and fell into some amazing rum. He didn’t know that rum pot-distilled and barrel-aged could be so amazing. He was introduced to that and immediately wanted to extend our brewing into distilling,”

VanderKamp’s passion and successful lobbying forged a path for craft spirits. But it also created a do-it-yourself attitude that emanates from Michigan distilleries, guiding both their cocktail menus and spirit production.

In addition to lobbying efforts to allow the production of whiskey, gin, vodka and other spirits, New Holland was a vocal advocate for a price reduction of state-level distilling permits. In 2005, nine years after New Holland opened its beer operation, the Michigan Liquor Commission dropped the price of a distilling license from $1,000 to $100. This allowed more entrepreneurs to participate in the dawn of Michigan’s craft distilling movement.

Already operating a full brewery and restaurant, New Holland was eager to put its recently acquired distilling abilities to use in cocktails for its dining patrons. However, to do so, New Holland’s distillers were compelled to learn an entirely new skill set: creating mixers and liqueurs.

“We designed our liquors simply with our bartenders in mind and to develop our cocktail program at our pub,” Blair said.

The idea of starting from scratch, as opposed to creating spirits from a simple list of accepted recipes, is the ironic result of a law that otherwise could have been a monumental impediment to a now thriving industry. With a recent regulatory history as prohibitive as the one in Michigan, distillers are willing now to work within a law that, if anything, forces creativity.

The result was a unique line of mixing spirits which included: First up, Clockwork Orange—A spiced orange liqueur made with orange peel, cinnamon, coriander and cardamom.

At first, the New Holland crew wasn’t sure how well Michigan craft spirits would be received, let alone if any of the niche products they created would catch on. But success was at hand.

“We didn’t realize that there was such a demand for a craft domestic orange liqueur,” Blair said. “We had bartenders from Chicago, specifically, that couldn’t comprehend why we weren’t putting that in a bottle so they could take it home and use it at their bars. After telling people ‘no’ for almost four years, we decided to give it a go and put it in a bottle.”

“We also make our own vermouth and we have a small bitters program. We play around with some interesting flavors,” Blair said.

Even though New Holland makes a line of bitters, this botanical-based creation is not a regulated item on the controlled liquor list. That means outside, third-party bitters can be used in their cocktails. However, many distillers would rather create their own infusions than work with standardized flavors.

Across the state, in the Detroit suburb of Ferndale, Valentine Distilling has garnered many medals and awards, including a Best of Class Gin from ADI’s 7th Annual Judging. But cocktails are the true passion behind Valentine’s craft.

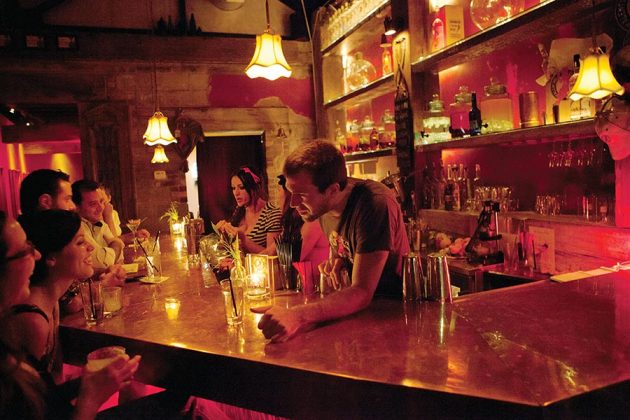

“I look at it this way,” owner Rifino Valentine said. “In Michigan, we were one of the first craft cocktail lounges. When we started, our focus was on making cocktails. Our in-house mixologist, Nick Brancaleone—I call him a liquid chef—he just focuses on flavors that work together, flavors that work with our spirits.”

Valentine Spirits, however, chooses to forego the use of liqueurs, and instead grows many of their own herbs and botanicals.

“We focus on the spirits. We don’t make liqueurs. The only mixers we make are non alcoholic,” said Valentino. Getting a little tongue in cheek, he adds “We use a lot of shrubs from local companies, and we grow our own shrubs as well. We use fresh ingredients and blend those flavors with our spirits. We use a lot of fresh herbs. We grow a lot of the fresh herbs that we use on site.”

Not limiting themselves to just herbs, Valentine makes use of berries, fruits and others grown by Valentine or procured seasonally at local farmers markets. “It’s a different approach, like a chef taking on a cocktail list,” Valentine said. “We keep with our staples, but we’re also always running special cocktails. We have a mulberry tree. When the berries are ready, sometime in August, we run a fresh mulberry cocktail.”

Both Valentine and New Holland have been at it for a while, and have found ways to work within the law to create cocktails that represent their values, and more importantly, enhance their spirits with class and distinction. But, startup distillers might find it more difficult to learn their craft while creating a full cocktail menu.

“Our primary focus right now is our spirits,” said Josh Cook, co-owner of the soon-to-open Revival Distilling in Kalamazoo. “Our primary focus is to get those spirits to local retailers and restaurants. We’re not spending as much time learning the cordials, making the mixers. We know its something we need to spend time on in the next few months when we get up and running.”

Revival’s aim is to produce spirits that pay homage to the pre-Prohibition style and spirit of the Kalamazoo area. Cook and his partner, Jon Good, have plans to oversee a full distillery/restaurant/tasting room, where customers can also enjoy well-made spirits and cocktails.

“We’re going to be leveraging the mixologists who are professionals in their trade, having people partner with us so that we don’t have to be experts in everything. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel. Jon and I are identifying things we need to spend time on, but we’re not concerned; we’re going to find a way to make it happen and make sure it’s done right,” Cook said.

Their anticipation aligns with new Holland’s experience.

“Going back to when we first started distilling, it was difficult to learn to do so many things so quickly. It takes a while to get your feet underneath you and to know how to make something, and to test it. You want it to be as good as possible. It takes a while to get that experience and get to a level that you’re comfortable with,” Blair said.