As most distillers know well, Uncle Sam makes a pretty penny on each bottle of alcohol manufactured in the United States. Federal excise taxes on distilled spirits are higher than those imposed on almost any other consumer good. When you add in state and local excise and sales taxes, domestic taxes can account for as much as one-half of a bottle’s sales price. And since these taxes are passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices, it’s no wonder distillers are looking to foreign markets for their products. This is because the federal excise tax is waived when alcohol is exported.

While distillers can catch a break by shipping their products abroad, they should be sure to investigate whether the receiving countries impose importation or other taxes. Indeed, deciding whether to export American-made spirits can be a balancing act. Shipping costs and taxes in other countries may offset the tax-savings realized by exporting. Nevertheless, as domestic taxes continue to remain high, it is certainly worthwhile for distillers to explore exportation as a path to financial savings.

The Federal Excise Tax

The federal government imposes excise taxes on various goods, services and activities. Unlike state sales taxes, which are imposed on nearly all goods as a percentage of the sales price, excise taxes are paid when purchases are made on a specific good. Federal excise taxes apply to a wide variety of products and services, ranging from alcohol and tobacco to indoor tanning, ozone-depleting chemicals, airline tickets and gasoline, and are generally perceived as an indirect tax levied on the producer or merchant who is then expected to pass on the cost to the consumer.

The United States began taxing distilled spirits not long after the nation was founded; federal excise taxes on alcohol have their origin in the Distilled Spirits Tax Act of 1791. Since that time, these taxes have served as a significant source of revenue for the federal government. A 2015 report by the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that alcoholic beverage excise taxes would result in approximately $10.2 billion of revenue in 2016. This is greater than the revenue projected from nearly all other excise taxes, with the exception of those on gasoline, airline tickets, tobacco and health insurance providers.

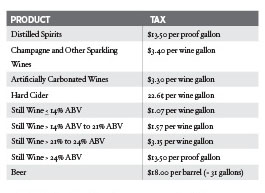

When it comes to the federal excise tax, not all drinks are created equal. Compared to wine and beer, the greatest tax by far is on distilled spirits, imposed at a rate of $13.50 per proof gallon. A proof gallon is a gallon of liquid that is 100 proof, or 50% alcohol by volume, at 60°F. By comparison, the highest tax on wine is $3.40 per wine gallon (defined as a gallon of liquid equivalent to the volume of 231 cubic inches), imposed on champagne and other sparkling wines. Artificially carbonated wines are taxed at a rate of $3.30 per wine gallon, while hard cider is taxed at the comparatively low rate of 22.6 cents per wine gallon [1]. All other “still” wines, or wines containing not more than 0.392 grams of carbon dioxide per hundred milliliters of wine, are taxed according to alcohol content. Still wines containing not more than 14% alcohol by volume are taxed at a rate of $1.07 per wine gallon; while those containing more than 14% but not more than 21% alcohol by volume are taxed at $1.57 per wine gallon. For wines containing more than 21% and not exceeding 24% alcohol by volume, the rate jumps to $3.15 per wine gallon. Wines containing more than 24% alcohol by volume are classified and taxed as distilled spirits.

Beer is taxed at a rate of $18 per barrel (the equivalent of 31 gallons). To put this into perspective, the federal excise tax on a 750-ml. bottle of distilled spirits (at 80 proof) is $2.14. The tax on the equivalent amount of beer would be slightly over 10 cents. It’s unclear why the tax on distilled spirits at both the federal and state level is so high compared to other alcohol, but a common hypothesis is that it is due to the higher alcohol content per drop, or unit, of distilled spirits. In response, some commentators have argued that taxes should be adjusted to reflect the respective contribution of each type of alcohol to overall societal costs. Under this analysis, they argue beer would bear the highest share of excise taxes because research suggests beer is most often linked with negative outcomes related to excessive drinking, likely because of its lower price relative to other types of alcohol.

Liability for the federal excise tax on distilled spirits arises when the alcohol is produced, but the tax is not determined and payable until bottled distilled spirits are removed from the bonded premises of the production plant. Likewise, liability for the federal excise tax on wine and beer accrues upon production, but it is not payable until the wine is removed from the bonded wine cellar or winery or the beer is removed from the brewery for consumption or sale. Generally, bulk distilled spirits and wine may be transported in bond between bonded premises and beer may be transported between commonly owned breweries without paying the tax. However, the tax liability follows these products and becomes due when the alcohol is consumed or sold.

In addition to federal excise taxes, states also impose significant excise taxes on alcohol, particularly distilled spirits. As of January 1, 2016, the highest excise taxes on distilled spirits were imposed by Washington, Oregon, Virginia, Alabama and Alaska. Wyoming and New Hampshire have some of the lowest excise taxes on liquor, followed by West Virginia, Missouri, Colorado and Texas.

Finally, the great majority of states impose sales tax on distilled spirits on top of state and federal excise taxes, and some states impose even more taxes! For example, Kentucky—the touted bourbon capital of the world—imposes an excise tax, wholesale sales tax, and retail sales tax on distilled spirits. Wholesalers in Kentucky are also required to pay a “case tax” on each case of distilled spirits sold in the state. In addition, unlike any other state in the nation, Kentucky imposes a property tax on distilled spirits located in a bonded warehouse. Thus, in addition to high federal excise taxes, distilled spirits may be subject to a variety of state and local excise, sales and even property taxes, all resulting in a bigger price tag for the ultimate consumer.

PATH Act

One recent piece of legislation with ramifications for the alcohol industry is the Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes of 2015 (PATH Act). The PATH Act was signed into law at the end of last year, but its provisions related to alcoholic beverages do not go into effect until 2017. The PATH Act removes the bond requirements and extends the filing due dates for certain taxpayers with limited excise tax liability. Starting with the calendar quarter beginning on January 1, 2017, taxpayers who reasonably expect to be liable for not more than $1,000 in excise taxes on distilled spirits, wine, and beer for the calendar year, and who were liable for not more than $1,000 in such taxes for the preceding year can pay these taxes annually, rather than quarterly. In addition, taxpayers eligible to pay alcohol excise taxes annually under these new provisions, as well as taxpayers currently eligible for quarterly filing under the law (i.e., taxpayers who anticipate being liable for no more than $50,000 in alcohol excise taxes and who were liable for no more than $50,000 in excise taxes the preceding year) are exempt from the requirement of furnishing a bond covering operations or withdrawals of distilled spirits or wine for nonindustrial use or of beer for any purpose.

Waiver of the Federal Excise Tax upon Exportation

The good news for distillers is that the high federal excise tax is waived if the spirits are exported from the United States. Federal law permits a proprietor to withdraw spirits from the bonded premises of the distilled spirits plant for exportation without payment of the federal excise tax. Exportation includes both shipments to a foreign country and shipments to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, the territories of the Virgin Islands, American Samoa and Guam and the Panama Canal Zone.

Distillers seeking to withdraw distilled spirits without payment of tax must complete TTB Form 5100.11, Withdrawal of Spirits, Specially Denatured Spirits, or Wines for Exportation. If the exporter is not the proprietor of the bonded premises of the distilled spirits plant (DSP) from which the spirits are to be withdrawn, the exporter must prepare TTB Form 5100.11 as an application; if the exporter is the proprietor of the bonded premises of the DSP from which the spirits are withdrawn, the exporter must prepare the form as a notice. In accordance with the instructions, the exporter must list the country of importation and describe the spirits to be exported.

Each package of spirits withdrawn without payment of tax must be marked with the word “Export” prior to its removal from the bonded premises. In addition, the proprietor must mark the word “Export” on the government side of each case or government head of each container before removal from the bonded premises for exportation. To be relieved of liability for the tax, the proprietor exporting the distilled spirits must maintain and submit proof of exportation, which may include a copy of the export bill of lading, a copy of the railway express receipt, a copy of the air express receipt, a copy of the through bill of lading where exportation is to a contiguous foreign country (i.e., Canada or Mexico) or a certificate by the export carrier. Further, the operations or unit bond required to be given by the distilled spirits proprietor to the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) in order to operate a DSP must cover the withdrawal of distilled spirits without payment of tax.

If TTB Form 5100.11 is filed as an application (as opposed to a notice), the appropriate TTB officer must approve the application if it has been properly executed and the required bond has been filed in a sufficient amount. The officer must send copies of the form to the proprietor of the bonded premises from which the spirits will be withdrawn.

Distillers can also submit a request to TTB to use an alternative export documentation procedure. The alternative procedure allows distillers to maintain copies of export documents, including Form 5100.11 and appropriate proof of exportation, at their premises as opposed to sending these documents to TTB. Distillers utilizing the alternative procedure must submit a monthly report of goods exported to TTB in an electronic spreadsheet and obtain acceptable proof of export within 90 days after the spirits are removed from the premises. Export documents must be retained for six years after the date of exportation. All proprietors of distilled spirits plants may request to use this alternative procedure by submitting a letterhead request to TTB. Distillers interested in this alternative procedure should review TTB Industry Circular 2004-3, available on TTB’s website at TTB.gov.

After spirits are removed from the bonded premises for exportation, they may be stopped for repacking purposes prior to being laden on board the export carrier if the following conditions are met:

- The foreign destination is established prior to removal of the goods from the bonded premises, and this is clearly reflected in the distiller’s commercial records;

- The goods are consistently moving, in accordance with good commercial practice, to the ultimate consignee and the shipping documents show a foreign country as the final destination; and

- The repacking is accomplished for reasons of economy or efficiency, with the goods consigned directly to the foreign customer/ultimate consignee.

Export certificates (such as Certificates of Origin, Certificates of Health/Sanitation, and Certificates of Authenticity/Free Sale, among others) may be required for alcoholic beverages to be imported into a foreign market [2]. These certificates can be requested from the TTB’s International Affairs Division [3] by mail or email using the TTB’s export certificate template, available on its website.

Another tool that should be available to distillers in the near future is the International Trade Data System (ITDS). ITDS is an interagency program that seeks to establish an electronic “single window,” operated by Customs and Border Protection (CBP), through which importers and exporters can electronically submit the data required by federal agencies for clearing imports and exports. Executive Order 13659, issued on February 19, 2014, requires agencies to be able to utilize ITDS by the end of this year. On June 21, 2016, TTB published a notice of proposed rulemaking proposing amendments to its regulations governing the importation of distilled spirits, wine, beer and malt beverages that will allow importers to file TTB-required data electronically through ITDS as an alternative to the current rules that require importers to submit paper documents to CBP upon importation. [4] The deadline for public comments was August 22, 2016. Currently, TTB is hosting a pilot program that allows participating importers to utilize ITDS to file their TTB-required data. Although a similar program is not yet available to exporters, TTB should be amending its export regulations in the near future to make them compatible with ITDS and allow exporters to take advantage of this streamlined procedure.

Distillers should also check the laws in their state of operation to determine whether alcohol produced for shipment out-of-state is exempt from state and local excise and sales taxes. Many states contain an exemption from tax for property that will be permanently shipped out-of-state (often referred to as the interstate or foreign commerce exemption).

A Note of Caution on Taxes Abroad

Although distillers can avoid domestic taxes by shipping their products abroad, they should be aware that foreign countries may impose their own taxes when spirits are imported. Two popular destinations for American-made liquor are Canada (because of its proximity) and China (because of the popularity of U.S. spirits there). Countries in Europe, including the United Kingdom (UK), France and Germany, are also popular destinations for U.S. distillers. Each of these countries imposes its own set of taxes on alcoholic beverages.

In Canada, imported spirits are subject to a customs duty, an excise tax, a “goods and services” tax and a provincial sales tax collected on behalf of the Canadian provinces; however, because the North American Free Trade Agreement created duty-free access for most beverage alcohol products imported into Canada from the United States, the customs duty does not apply. The excise tax on spirits is imposed at a rate of $11.696 per liter of pure alcohol, although spirits containing not more than 7% absolute ethyl alcohol by volume are taxed at a rate of $0.295 per liter of spirits. The goods and services tax is levied at 5% of the retail price of the goods. The provincial sales tax varies depending upon the province. For example, the provincial sales tax on liquor in British Columbia is imposed at a rate of 10% of the purchase price. In China, distilled spirits are subject to three separate taxes: an import tax, a value added tax (VAT) and a consumption tax. The rates for each of these taxes vary depending upon the product and are compiled into a formula used to determine the effective tax rate.

France, Germany and—at least for now—the UK are member states of the European Union (EU). The UK voted to leave the EU earlier this year, but it will be at least a couple of years before “Brexit” takes effect and the UK officially exits the EU. When that happens, it may impact the taxes imposed by the UK on goods and services, including imported spirits, since the UK is currently subject to certain minimum rates set by the EU with respect to the VAT and excise duties.

All countries in the EU must impose the VAT on goods and services bought and sold for use or consumption, including imports. The VAT is charged as a percentage of the sales price. EU law sets a minimum standard VAT of at least 15%, but member states are free to impose higher rates. Spirits, wine and beer are subject to the standard VAT of 20% in France and the UK and the standard VAT of 19% in Germany.

EU law also requires member states to impose excise duties on certain goods, including alcohol. The rate varies depending upon the type of product—i.e., beer, wine, spirits or “intermediate products,” such as port and sherry. With respect to spirits, EU legislation sets a minimum excise duty of 550 euros (the equivalent of $613.89) per hectoliter of pure alcohol. Most member states, however, impose much higher rates. Germany imposes an excise duty of 1,303.00 euros per hectoliter of pure alcohol, France imposes an excise duty of 1,737.56 euros per hectoliter of pure alcohol and the UK imposes a high excise duty of 3,754.58 euros per hectoliter of pure alcohol. In the UK, for example, this is the equivalent of approximately 37.55 euros, or $41.91, per liter of pure alcohol. In addition to the VAT and excise duties, customs duties, which are calculated based upon the value of the goods, will apply to spirits imported into

the EU.

Like Canada, China and member states of the EU, many foreign countries do impose their own taxes on imports, including spirits. Therefore, it is important to do your homework before deciding whether exportation is the best course of action. However, exportation is certainly a viable option to explore, particularly given today’s global marketplace and the popularity of U.S.-made liquor abroad. After all, Americans aren’t the only ones who enjoy American-made spirits—and for good reason!

Footnotes:

1 The PATH Act modifies the definition of wine eligible for the comparatively low tax rate applicable to “hard cider.” See TTB.gov, “TTB Announcement – IRC Amendments Affecting Excise Tax Due Dates and Bond Requirements for Eligible Taxpayers and Revision of Hard Cider Tax Class – Effective in 2017” (Jan. 14, 2016), available at https://www.ttb.gov/announcements/ttb-announcement-cider-statutory-changes.pdf; see also Protecting Americans from Tax Hikes Act of 2015, Division Q of Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2016, Pub. L. No. 114-113 § 335. The Act increases the allowable alcohol content for hard cider from less than 7% to less than 8.5% alcohol by volume, increases the allowable carbonation level from 0.392 to 0.64 gram of carbon dioxide per hundred milliliters of wine, and authorizes the use of pears, pear juice concentrate, and pear products and flavorings. Id. These changes apply to hard cider removed after December 31, 2016. Id. This is a favorable change for the alcohol industry, as it increases the allowable alcohol content of wines that qualify for the favorable tax rates applicable to hard cider.

2 See TTB.gov, International Affairs Division, “Exporting Alcohol Beverages from the U.S.”, available at https://www.ttb.gov/itd/exporting_documents.shtml.

3 The TTB’s website at https://www.ttb.gov/itd/interre1.shtml provides a guide compiled by the International Affairs Division summarizing information about many countries’ import and export requirements, including licensing, labeling and taxation considerations. It is a good starting point for distillers but it is not necessarily comprehensive or updated and does not cover all countries.

4 See TTB Press Release, “Proposed Amendments to Streamline Importation of Distilled Spirits, Wine, Beer, Malt Beverages, Tobacco Products, Processed Tobacco, and Cigarette Papers and Tubes and Facilitate Use of the International Trade Data System” (Jun. 20, 2016), available at https://www.ttb.gov/press/fy16/press_release_fy-16-14_notice_no_159-itds_nprm.pdf.

Stacy C. Kula, Esq. is an alcohol beverage, hospitality and corporate law attorney, practicing out of the Lexington and Louisville law offices of Stoll Keenon Ogden PLLC. She is the Chair of the Alcohol and Hospitality Practice Group. Kula works closely with distilleries, breweries and retailers, helping them navigate through the difficulties of federal and state licensing, enforcement, corporate and contractual issues. Despite practicing in the Bourbon epicenter, Stacy’s favorite alcohols are spiced rum, gin and limoncello, but she’s always willing to sample the newest product on the market! She can be reached at (859) 231-3054.

Madonna (“Maddie”) Schueler is a tax attorney, practicing out of the Lexington office of Stoll Keenon Ogden PLLC. Her practice covers a wide variety of tax matters, including state and federal excise taxes on distilled spirits. She frequently assists clients with complex matters of taxation and litigates tax disputes. Schueler enjoys being a member of the firm’s Bourbon Chase team each year—a 200-mile relay race through Kentucky’s beautiful distilleries!