Alan Bishop and his family have some history in distilling, and he has grown into someone who embodies the designation “master distiller,” even though he shies away from the tag. I’ve known Alan for over five years, and we always have a good time when we’re together. So when I took the trip up north to see him at the Spirits of French Lick distillery in West Baden Springs, Indiana, I knew I was in for a treat. My wife and I had been to visit him once before in 2016, right after the distillery first opened. It was just getting up and running then, and I was looking forward to seeing just how much the place had grown in over two years. What I found was a humble man with an uncommon passion for the history and craft of making alcohol.

Alan started working at age 15, trying to become a gentleman farmer on his family’s property. Back then his dad was friends with some folks who were on a moonshining reality TV show. Alan was never in the series, but he spent some time occasionally around the show’s stars off camera. He even traveled with a couple of them for a while to meet-and-greet sessions around the country after they became celebrities.

The story I got from his wife, Kimberly, is that he still watches it on occasion when he wants to exercise his lungs. Screaming at the television when they’re doing something wrong or dangerous simply for the reality of it “is a little cathartic,” he’ll tell you. The two of us were invited to work at George Washington’s Mount Vernon historic distillery in March of 2018, and even after the amount of time that he’s been distilling commercially, it became obvious to me that he knew how to craft new-make using a wood-fired pot still.

It was this talent that landed him a distilling job in Louisville, Kentucky, where we met. He said that “farming wasn’t going to pay the rent as I had hoped, so in 2013 I started sending out random résumés,” offering his services as a distiller. Two that he recalled responding were Peerless and Copper & Kings distilleries. It was the latter that hired him in 2014 in Butchertown, an area east of downtown Louisville. Vendome Copper and Brass Works was installing the original two stills at that time, and owner Joe Heron introduced us as I was doing some work on the nameplates. Alan stayed at Copper & Kings for 18 months and helped them develop several different brandies and gins. The absinthe he created was a real standout.

In November of 2015, John Doty of French Lick Winery in Indiana called and asked him if he would like to be their head distiller. The winery started in 1995 in the old Ballard Mansion but moved to the empty Kimball Piano factory in 2001. Spirits of French Lick was just getting its equipment in, and the owners offered him complete control over what was being distilled, which is a privilege he had not had at previous jobs. A major bonus was that French Lick is a lot closer to where Alan and his family live in Pekin, Indiana. It didn’t take him long to give his notice at Copper & Kings.

When I arrived, I told the young lady in the gift shop I had an appointment with “Mr. Bishop.” I found out later she had to ask another employee who Mr. Bishop was. Alan, due to his humble nature, wouldn’t want anyone to call him that, so I’m sure he hadn’t told her his last name.

There aren’t many facets of spirit history or pieces of distillery equipment that Alan hasn’t studied, and his familiarity with multiple distillates always amazes me when we talk. His love of researching past distilleries in the counties where he lives and works has led to him become something of an amateur archaeologist, and this in turn has helped a few of the local historical societies map locations that had long been forgotten. He wrote and self-published a 98-page treatise, The Alchemist Cabinet Volume #1, and he runs a website with the same name. (https://alchemistcabinet.wordpress.com/) During the summer, he and his extended family travel on some weekends to perform as a historical troupe at festivals and fairs. “Hell’s Half Acre — Hellbilly Burlesque Show” is a reenactment that teaches some of the history of southern Indiana distilling in a raucous, black-powder-fueled, comedic ad-lib.

Alan and his two stillhands, Stephen McNeely and Tyler Divine, employ equipment manufactured by the Chinese firm DYE. In one room of the distillery, along with a 300-gallon corn cooker and six 1,200-gallon enclosed stainless fermenters is Lilith, a 1,200-gallon hybrid stripping pot still. She has a lamp glass-style helmet next to a four-tray bubble cap column that can be vented into a stainless vertical condenser. In a separate room are the two doubling pot stills: Inanna (600 gallons) and Sophia (350 gallons). Sophia is a hybrid still with a four-tray column atop her onion. Her column is capped by a stainless dephlegmator. There are additionally two stainless steel continuous columns that they incorporate depending on the spirit they’re distilling. For experimental purposes, there’s a one-gallon copper pot still named Dianna with a copper worm tub condenser.

Alan is on the side of distillers who name their pot stills, giving them feminine names because of their beauty and “motherly functions of birthing a spirit.” The honorific of mythical goddesses has always been his preference for their names, paying tribute to the magic and power of those deities. “I wouldn’t sail on a ship with no name and I won’t ever work a pot still with no name,” he says.

Bishop is one of the most accomplished distillers I know, owing in great part to his absolutely fanatical practice of biodynamical distilling, which he believes imparts terroir. He keeps a written record of each day’s temperature, humidity, sun or cloud conditions, season and phase of the moon. He also records his mood during each day, often saying, “My attitude during that run will definitely play a part in the finished product.” It’s not hard to imagine Alan 1,500 years ago, slathered with some warm, fermented mash, chanting around a huge bonfire to some mystical creature under the full moon.

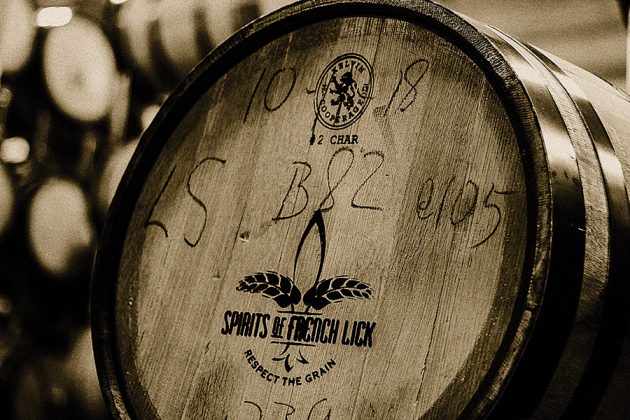

Including heirloom strains of corn in his past and present mashbills is something he has worked on for a long time. Toward the end of the tour of the distillery rickhouse, I noticed a pallet with six five-gallon buckets of dried, hand-picked and cleaned Amanda Palmer corn. This particular strain started out a couple of years ago as an experimental eighth of an acre. It now covers 18 acres and is the grain that’s the backbone of their signature bourbons. “Respect the Grain” isn’t just a slogan or a logo on every bottle: Alan and the crew take it to heart in every step of distilling.

That’s a huge reason for the number of awards they’ve received through the first three years of operation. Some that Alan is most proud of are the ADI 2018 Gold and Best of Category for the Old Tom Gin, the Great American International Spirits Double Gold for the Maple Aquavit, along with numerous medals in 2017 and 2018 for the Spirits of French Lick Absinthe. It won’t be long now, since the bourbons are being bottled, before they’ll need extra space in the trophy cabinet for more “precious metals.” If you see either the four-grain or the wheater, I recommend you don’t pass them up. The last part of my visit and a big sign of his personal dedication is the recent construction of a 3,000-barrel Dunnage-style rickhouse — more than doubling the 1,200 barrels already stored in the distillery. He’ll probably never like being called a master distiller, but if you ever get a chance to visit him in French Lick, please go, because after you meet him you’ll agree that the designation is well deserved.