Craft distilling is the heart and soul of the alcohol movement. Many craft distillers began as hobbyists, keeping their day jobs while focusing night and weekend efforts on perfecting their spirits. And those efforts paid off: the industry is booming and many of those distilleries have grown beyond their expected capacity, forcing the owners to quit their day jobs and focus on the business of distilling.

Even though the alcohol beverage industry is one of the most heavily regulated industries, most craft distilleries operate on a shoestring and legal advice is often considered an unnecessary expense. While the immediate benefit can be difficult to measure, there are key concepts particular to the alcohol industry that every distiller should know, and it is important to consult with an attorney who practices in the areas of both corporate law and alcohol law. Documents drafted for distillers need to be written by attorneys who understand distillers.

Increasingly, distillers are getting into business with multiple investors and owners, organized as such to raise capital and limit financing. It is important to remember that these investors must be eligible to hold an ownership interest in a distillery. To protect the distillery and its owners from running afoul of these legal nuances, special attention should be paid to the following when operating a distillery: (1) preformation activities, (2) governing documents and, (3) employment agreements.

Preformation Activities

Regardless of the number of investors, screen them prior to giving them an ownership interest in the distillery to make sure they are eligible to hold the necessary licensure under both federal law and state law.

Under federal law, a distiller applying for an operating permit:

- Cannot have been convicted of a felony in the past five years.

- Cannot have been convicted of a misdemeanor under Federal law related to liquor (including the taxation thereof) in the past three years.

- In the case of an entity, any of its officers, directors, or principal owners cannot have been convicted of those crimes.

- Such person must be able to establish that he or she has the business experience, financial standing or trade connections to be able to commence business as a distiller within a reasonable amount of time and in conformity with federal law.

- The proposed distillery operations are not in violation of state law.

State laws vary, but most states typically impose far more requirements on a prospective owner of a distillery than does federal law. Generally, state law will address the following: - Minimum age requirements—Most states will not allow an investor to hold an interest in a manufacturer unless they are 21 years of age or older.

- Criminal conviction requirements that may be different than federal law.

- Revocation of other alcohol licenses—A revocation of one type of alcohol license may prevent you from obtaining another within a certain timeframe.

- Holding licenses considered incompatible with the one for which you are applying—if the distillery is located in a state that adheres to the three-tier system, the owners of the distillery typically cannot hold licenses at more than one tier unless a specific statutory exception exists.

- Whether activities at other tiers (e.g., wholesale or retail tiers) by family members affect your license. In some states, if your wife, child, or parent owns above a certain percentage of a retailer, you cannot have an interest in a manufacturing operation.

Also remember that the granting of a state distillery license is usually within the state’s reasonable discretion, so there may be considerations other than those specified by statute that could prohibit you from obtaining the license.

When determining whether the potential investors can become owners, record their answers in writing. TTB and ABC applications are filed under penalties of perjury, and having done your due diligence by asking the proper questions—which you can prove in writing—can be a defense to a perjury charge.

In addition to making sure the investors can meet the statutory requirements, also collect from the investors all of the information needed to complete the distillery’s federal and state applications. Once the potential owners actually become owners, they are notoriously unresponsive to additional requests for information.

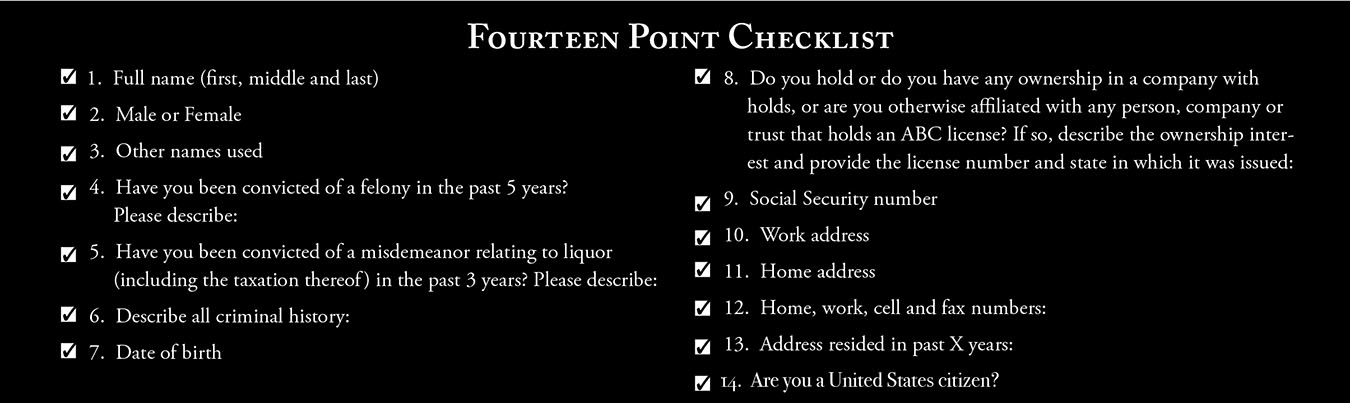

Below is a general checklist that can be easily conformed to each state’s specific requirements to determine whether someone is eligible to own an interest

in distillery.

Governing Documents

Every distillery that has two or more owners should be established as a limited liability company (LLC), a corporation, or a limited partnership to shield the owners personally from certain liabilities, assuming that state law allows that type of entity to hold a distiller’s license. For an LLC, the document governing the rights and responsibilities of the owners is called an operating agreement; for a corporation, it is called a shareholder’s agreement; and for a limited partnership, it is called a limited partnership agreement. These governing documents must be specifically tailored to take into account the alcohol laws.

After the business is formed, and your once potential investors have become owners, what happens if a previously eligible owner now does something and becomes ineligible? What happens if an owner gets a DUI, or purchases an investment in a retail establishment? What happens if your partner dies and his 19 year-old son inherits the business? If you cannot rectify the situation quickly (i.e., before the TTB or ABC knows about it), your distillery could have its license revoked.

Buy/Sell Provisions

To avoid or to have the ability to rectify these situations, you will need the ability to divorce yourself from your partner. If you cannot force an ineligible owner out of the company, that person may cause the loss of the distillery’s licenses. And here’s the kicker: Under most state laws, you cannot force them out unless you specifically include a provision in your governing documents that says you can.

Such provisions are called “buy/sell provisions,” and they are invoked upon the occurrence of an event that forces an owner to sell his or her interest or gives the company or the remaining owners the option to purchase the interest.

Forced Buy/Sell

In a forced buy/sell provision, the occurrence would be the owner becoming an ineligible owner, which could threaten the distillery’s license. Generally, the distillery or the remaining owners would buy out the ineligible owner and pay the purchase price over a period of time. A five-year payout, with or without interest, is not unusual. Remember, it is the ineligible owner’s bad acts that caused the need to buy them out, so the agreement should aim to protect both the distillery and the remaining owners from suddenly finding themselves in a precarious financial position. As such, the buyout period should give the purchaser enough time to raise the funds to pay the purchase price without severe economic impact. (Purchase price can be determined several ways, but that’s a topic beyond the scope of this article.)

Although not necessarily tied to alcohol operations, there are other possible transfer provisions important to consider in a distillery’s governing documents. The laws of some states allow an owner to freely transfer his or her interest unless the governing documents prohibit such transferability.

Right of First Refusal

If you have agreed to invest all of your savings into a business with your life-long best friend, or with a master distiller with proven experience, you do not want that person to be able to sell their interest to someone with whom you do not want to do business without first offering it to the other owners. This provision is called a “right of first refusal.”

Involuntary Transfer Provisions

You should also consider incorporating involuntary transfer provisions into your governing documents. These provisions are invoked upon an occurrence that can cause an interruption in your business. For example, your partner gets divorced (and you do not want to work with the former spouse, who could receive the interest in the company in a divorce settlement), or your partner goes bankrupt (and the new owner may be whomever the interest is sold to in the bankruptcy proceeding).

Deadlock Provisions

There are also “deadlock provisions,” invoked when the owners either cannot agree on a major business decision or just no longer get along. Under these provisions, one owner names the price and terms, and the other owner decides whether he wants to buy the first owner’s interest or sell his interest to the first owner. In practice, if the parties have disparate financial conditions, such provisions can be easily manipulated.

While these general types of buy/sell provisions are commonly found in governing documents, consult with a corporate attorney to ensure that these provisions are enforceable in your state.

Reporting Requirements

In addition to the buy/sell provisions, your governing documents should include representations or promises from owners that they will immediately report, or take, certain actions, and if they do not, there are penalties. Any change in information reported on the federal or state application usually necessitates that an amendment be filed with the TTB and ABC. If the distillery fails to report the changes, the business could be cited. This includes not only changes that make an owner ineligible, but also any change in information reported on past applications, such as an address or phone number change. The penalties an owner may face for failing to comply with reporting requirements can range from paying the distillery’s attorney fees to forfeiting their interest in the distillery.

Consider also incorporating a provision that requires all owners to promptly sign documents. A distillery must renew its state licenses and may have reporting requirements where one or more owners’ signatures are required. An unresponsive owner could cost the distillery its license. Again, silent investors can be difficult to reach.

In addition, consider getting an express consent to obtain—or have the owner agree to obtain—criminal background checks. Many states require verification of an owner’s criminal history, and without that owner’s cooperation, they can be difficult or impossible to obtain.

Powers of Attorney

If an owner is unresponsive, or if there is a falling out between owners and one owner refuses to cooperate, the distillery’s governing documents should include, to the extent allowed by state law, an irrevocable power of attorney that allows other owners or officers to sign documents on behalf of the uncooperative owner in limited circumstances.

If the distillery has already been formed but there are no governing documents, or the governing documents do not contain the proper buy/sell provisions, it is not too late. Talk to the other owners and put an agreement in place now before an issue arises.

Employees

Very high-level employees who are not owners, like officers or the master distiller, are often required to be reported on the applications. If these employees engage in certain bad acts, they can also cause the loss of the distillery’s license.

I am not necessarily suggesting that you enter into an employment agreement with these people, but if you do, you need to make it clear that any activity on their part that endangers the distillery’s license is grounds for immediate termination.

In today’s competitive marketplace, distillers cannot just make good hooch anymore. They need to make good business decisions as well. Proper corporate governance will protect not only the owners, but the distillery’s business, too.

The author would like to thank Hannah Simms, a Summer Associate at Stoll Keenon Ogden, PLLC, for her help in researching the materials used in this article. 7