“It is a type of alcohol that we in the West know nothing or very little about; and since we don’t know much about it, we don’t really give a shit. But when you begin to know something, it becomes a lot easier to understand and appreciate.”

That’s how Darrell Corti, the eclectic groceryman from Sacramento — ever the provocateur about all things alcohol — summed up the world’s largest-selling spirit from a hospital bed where he was recovering from a nasty tussle with kidney stones.

With nurses interrupting, we were discussing baijiu, a clear spirit, high in proof, drunk usually ceremoniously at banquets and highly collectable by the Chinese. It is mostly consumed in China, in several distinct styles, and has recently gained a foothold — albeit more of a baby bootie-hold — in the states. Thanks in part to Corti, Vinn Distillery near Portland, OR, became the only distillery producing baijiu domestically. Although Corti’s diverse stores, Corti Brothers, carry Vinn’s products, sales of 80- and 106-proof baijiu are miniscule.

“It’s selling slowly, but worldwide, it’s an important product,” Corti explains as the caregivers check to see if he’s still in pain. He continues resolutely, stating that if baijiu is going to catch on here, “It’s a question of time. In 1959, no one knew what Smirnoff Vodka was.”

Corti admits he knew nothing of the white alcohol — the literal translation of baijiu (traditionally pronounced “bye joe”) before it popped up in an article on his computer only last year. It was the drink served in tiny glasses that Chinese premier Zhou Enlai used to toast Nixon when the US president visited China in 1972. Nixon, ever marching to his own drum, drank the stuff in spite of warnings from his advisors, who suggested he only pretend to imbibe.

Baijiu is one of the rare spirits created by parallel fermentation. Most alcohol is produced in two steps: first, a grain is soaked in water and malted, which converts its starches into sugars, and then it is fermented, which is the process by which those sugars become alcohol. For hundreds of years, baijiu manufacturers have carried out both processes at once. The grain for Vinn and many baijiu distilleries in southern China is rice. In Vinn’s case, it’s the Calrose brand from central California. It is cooked and then combined with a fermentation starter, called the qu (pronounced “chew”), a mix of rice flour and a recipe of herbs and spices. The mixture simultaneously converts rice starch into sugars while those sugars ferment, a process that takes six months. The fermented liquid is then transferred to pot stills, distilled and left to age one to three years. It is this parallel fermentation that is responsible for baijiu’s funky aromas and flavors, with which Americans struggle.

The Ly family’s Vinn baijiu, however, seems to have mitigated that fetidness, due mainly to the use solely of rice for fermentation, rather than the more commonly used sorghum. My sampling of Vinn’s 80-proof baijiu ($44 at Corti Brothers) revealed a clean, albeit goodly waft of alcohol with an undertone of rice aroma and flavor, not unlike sake. The Family Reserve ($73), although it’s 53 percent alcohol, was much smoother, with more subtle floral notes on the nose, and there was a scrim of rice on the viscous, full-bodied, velvety mouthfeel.

In China, distillers turn out more than 10 million liters a year. In the US, which currently has only the one baijiu distillery, they’re turning out less than 1,000 cases per annum. Vinn Distillery of Wilsonville, OR, 18 miles south of Portland, has been making rice-based baijiu for 10 years.

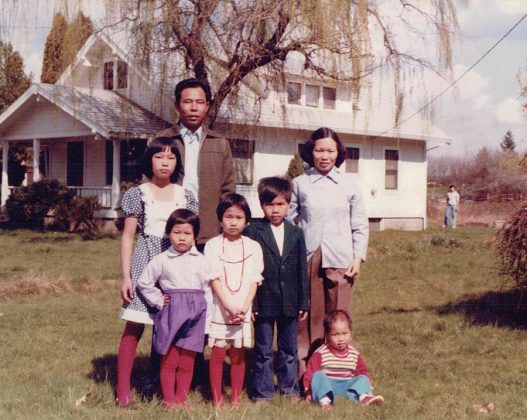

The Ly family — with a quintet of siblings, all with the middle name of Vinn — originates from Vietnam via China. Here in Oregon, they’re making baijiu in a simple pole barn behind their home. Their father’s family had been making baijiu for centuries. The distillery — now run by the ninth generation of baijiu-makers — produces whiskey, vodka, fruit liquors and America’s first baijiu. While companies often import baijiu into the US, none make it, according to a Vinn spokesperson, from scratch, as does the Pacific Northwest distiller.

Every summer, the siblings and their mother make qu. Like a sourdough starter, the qu is filled with yeast and enzymes. Baijiu makers form qu bricks or balls and add them to the cooked grains to start fermentation. It’s usually distilled in pot stills, as are many spirits. (Vinn’s rice-aroma baijius are distilled in continuous stills.) Qu is the combination of yeast, mold and bacteria that breaks down grains and ferments them at the same time.

Most baijius are aged in nonreactive and breathable ceramic vessels, allowing oxygenation. Vinn is looking into utilizing ceramic, but so far hasn’t found any to its liking or ones that fit into its budget.

Vinn’s style of baijiu is more common in southern China, where more rice is grown, than in the north, where wheat-based, brick-like “big qu” is dominant. The rice fragrance is a feature of southern Chinese baijiu. Other styles and fragrances of baijiu are “strong aroma” from Sichuan, made from sorghum; “light aroma” from northern China and Taiwan, from sorghum and rice husks; and “sauce aroma” from southern Sichuan, also produced from sorghum, but with an aroma of soy.

Some of the best Chinese baijiu is made in temperate zones. Michelle Ly, the spokesperson for Vinn, is unsure how much the Pacific Northwest climate influences its baijiu. Vinn’s standard baijiu is 40% ABV, intentionally low for a baijiu so as to “meet the expectations of Americans” used to relatively feebler spirits. But as a tribute to their father, the Lys also sell his preferred baijiu, the potent 106-proof offering.

Why then make baijiu from rice and not sorghum, which possesses more of the idiosyncratic aromas that most Chinese favor?

“If you compare ours to strong aroma, ours is very approachable,” Ly says, while conceding that the conventional preference in China leans toward the funky, potent side, which accounts for 75 percent of all baijiu sales. That said, Kweichow Moutai, the top-selling, most famous and (valuable) baijiu brand, is not strong aroma but sauce aroma. “(Many) think ours is too light,” Ly says. Officially though, there are a dozen styles of baijiu.

Ly explains further her family’s pragmatic use of rice, “We’ve always had rice available (in Vietnam and the US) and not sorghum. You used what you had. Rice paddies are found all over southern China and northern Vietnam. Our parents worked in rice paddies every single day.”

Does Ly believe there is a market for baijiu in the US. In addition to Sacramento, Vinn’s baijius are on shelves in San Diego, San Francisco and Washington State.

“People are now exploring different spirits, and finally baijiu has taken that turn,” she opines. However, she cautions, “The flavor is off-putting if you drink poorly made baijiu. When we explain what to expect, they are more embracing; people appreciate the unique flavor and aromas.”

What does Darrell Corti think about baijiu, which he chose to place in his store and which is selling “very slowly”? Will Americans embrace baijiu?

“There are a lot of different drinks in the world — for instance, from Mexico. Twenty years ago, no one had heard of mezcal. There are a lot of things from around the world we know nothing about, and a lot are worth exploring. (It’s popular) among the Chinese community, and in New York there are at least three baijiu bars.” (Research on baijiu bars revealed liquid results, but there is at least one Manhattan boîte that is devoted exclusively to serving baijiu-based cocktails and several others that have baijiu drinks in their lineups.)

I put the question in an email to Derek Sandhaus, author of Drunk in China: Baijiu and the World’s Oldest Drinking Culture, about the efficacy of baijiu ever gaining market share here. In the message, I wrote that I’m of the opinion that the drink is not for everyone but will appeal to the iconoclasts among us. He responded: “With respect, I disagree with your assessment. Baijiu is the most popular distilled spirit on the planet, and I think it is a mistake to ignore the tastes of the hundreds of millions of people who drink and enjoy it, or to assume that we can’t develop similar tastes ourselves. Many liquor categories that seemed unfathomably alien to American drinkers in recent memory — tequila, mezcal, amaro, etc. — have all found acceptance in the international mainstream. Is it a drink for everyone? Probably not, but it’s certainly not a drink for no one. I believe baijiu will follow a similar trajectory and carve out a loyal following, it’s just currently in the early stages of international understanding and these things take time.”

Why does he believe that?

“First and foremost, baijiu will find an audience in America because it’s a great drink when made well,” he writes. “Moreover, baijiu rewards the curious drinker: It’s in a diverse category of spirits that contains at least a dozen sub-categories, each of which could be considered a unique spirit in its own right. Moreover, many of the combinations of flavors found in many baijiu styles can’t be found in other spirits, so it opens up a lot of food and drink-pairing possibilities to the inventive bartender.”

Has he tried Vinn’s baijius?

“I have had it many times. I use it as part of my tastings whenever I teach classes about baijiu in the United States.”

His assessment?

“I think it’s an excellent example of rice-based baijiu style popular in southeastern China, what they call rice-aroma style (mixiang xing 米香型) in China. It is approachable, mild and easy to drink and mix. It reminds me of the best you get out of a milder sake or soju, where you can taste the cooked grain but also get a few accents that come from the unique fermentation process: light floral and lemony notes.

“In my experience most spirits drinkers accept this style of baijiu much more readily than more pungent varieties, and given its mildness, it is quite easy to mix. In many ways, rice baijiu often surprises people who have reacted negatively to sorghum-based baijius.

“It’s also important to remember,” he continues, “that Chinese food has always been one of the most popular cuisines in the United States, and no drink better complements Chinese food than Chinese alcohol. In China, baijiu is always served alongside food, and both seem to bring out the best in each other. As regional Chinese cuisine becomes better understood and appreciated in America, I think baijiu will also find a home in the dining world.”

What foods should distillers, bartenders and consumers consider that would go well with baijiu?

“The rule of thumb for baijiu pairing is to match the baijiu with the food from the region where that style originates,” Sandhaus says. “Rice baijiu comes from Guangxi and Guangdong provinces, where the cuisine is fairly mild and uses lots of seafood. Think steamed fish, rice vinegar, dumplings and the like. Cantonese barbecue would work as well.

“The Ly family comes from just south of the Chinese border along Guangxi Province, where the food also has a little bit more sourness to it, so I think that vinegar, perhaps quick-pickled vegetables, would also work.”

None other than the Ly family should know what foods have an affinity with baijiu.

Michelle Ly thinks that steamed chicken dipped in ginger, soy or fish sauce with cilantro and mint is a natural pairing, as is steamed or salted fish with sautéed vegetables. Ginger or citrus added to baijiu cocktails are a sterling complement.

The Ly siblings, all of whom have “day jobs” to offset the rather limited revenue they derive from the small Vinn operation, have plans to expand, another indicator that baijiu might be having its moment here. But like most small, family-run businesses, the Lys’ approach is more visceral than technical. They literally follow their noses, making a spirit that often — but not theirs — makes proboscises turn up.

“We approach distilling and making baijiu not from a scientific way, but more of an art form,” is how Michelle Ly characterizes Vinn’s methodology. “We produce it the way we’ve been taught. We were taught by our dad (who died in 2012), who was taught by his dad. We distill based on the smell.”