Big drops of rain hit the sidewalk along the path from the gate to the main door of Leopold Bros. distillery in Denver. The smell of spring rain fills the air. Todd Leopold greets me outside the building in his trademark Carhart overalls and invites me into the tasting room.

The distillery’s latest accolade sits on the counter behind the bar, the Bubble Cap award for Distillery of the Year. “I thought I was going to be a teacher way the hell back in high school. That’s what I thought my calling was. Then I thought brewing was my calling until I got my hands on a still and that was the end of that,” Leopold says.

Consumers love their products. Distillers respect them and to top it off they have a gorgeous new facility filled with stills, fermenters, a malthouse and barrels of whiskey. It all looks effortless. That is the epitome of talent. But Leopold Bros.’ success is anything but effortless. Leopold explains what he and his brother Scott have been through, “For the first 8–10 years we weren’t making any money. It’s not so bad now. He put his faith that his younger brother could make palatable beer and then palatable spirits. He’s been nice enough to tell me that he hasn’t regretted coming into business with his dumb brother. What a gamble. And for many years it was a bad bet.”

A doorway opens into the large production room. Eric, one of the brothers’ long time employees, stands on a ladder, cleaning the mash cooler. The aroma of fermenting mash hangs in the air. “It’s a tough business,” Leopold says. “It’s very physical; you’re cleaning most of the time. If you’re not the person that gets to do the creative side, it’s a tough way to make a living. The people who work for us are family. Eric is family. Our goal is to make sure they never leave. For us that’s the best part of this, yes it’s because I love making spirits, but the more important thing is the people.”

Leopold pulls a step up to one of the open top fermenters for me to stand on. Sixteen of them sit in rows near windows leading to the garden outside. Bourbon mash ferments away, thousands of tiny bubbles erupting on the surface. “I’m always reading and trying to get better. I make sure Scott is proud of what we’re putting in the bottle.”

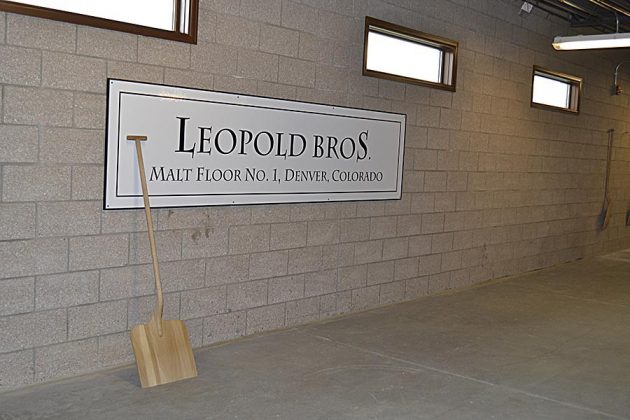

We head into the malting room. It’s clean and stark. A malt grubber and a few malt shiels lean against the walls. Leopold explains floor malting and the importance of quality barley; and again, he makes it sound easy. “Most of the work has already been done,” he says. “You get it wet, you keep it cool. You make sure it doesn’t get tangled, you try to make sure you designed the kiln well so the heat is nice and even.”

Stepping outside reveals the malt kiln; a small white stucco structure capped with a traditional copper pagoda. He opens the door and reaches down, scooping up some barley. It tastes familiar and sweet. The texture is tender and flaky. “For me consistency is one thing and really just not screwing up what the Colorado farmers did. I know that is going to make nice flavorful malt.”

A few raindrops begin to fall again as we walk towards the rickhouse. It’s a non-descript warehouse: white walls, no windows. Inside it becomes clear it’s not like most warehouses. Concrete paths traverse the building but bare earth lies beneath our feet. Half of the rickhouse is lined with barrels, mostly American whiskey barrels with a dozen or so used sherry barrels. The other half houses the less-romantic supplies a distiller needs: boxes, barrel racks waiting to be assembled, a forklift. The chatter of rain on the metal roof begins to drown out his voice and the air feels cool.

We head back to the tasting room and he pours me a sample of their latest release, Aperitivo. The tasting room is simplistic at first glance but there are elegant details all around. I can’t help but wonder what Leopold Bros. brewery was like back in Ann Arbor, MI.

“Running a bar is a young person’s game,” he says. “I really enjoyed that. It was fun, the hustle and bustle of a bar, but that’s a tough business. I cannot imagine running a bar right now, the midnight phone calls and the ice machine breaking down on Friday night. But we met some really wonderful people; had some great regulars, so many people coming in and out that were doing great things because it was a college town.”

The conversation shifts to the inevitable topic of the increase in number of distilleries. “They don’t understand you can either not do well and that’s what keeps you from getting paid, or you can DO well and that’s what keeps you from getting paid because you’re taking that money and buying new equipment and adding new people. I ask them ‘How do you feel about not making money for 10 years?’ It’s a tough business to get into.”

Then there are the consumers.

“This whole plant is designed around education,” says Leopold. “We designed it on trying to get people to understand how these things are made. What’s helping the brewers so much is they have a deep bench. They have hundreds of thousands of people in Colorado who can name a couple hop varieties, which is kind of crazy, if you think about it. How the hell do you know what Simcoe or Cascade hops are? It’s quite a detail. I’m jealous of them. I wish consumers were as educated about spirits as they are about beer because if they were, they could easily support the 60 plus distilleries in the state of Colorado. It’s our job to play catch up. That’s why we do so many tours here. Education is where it’s at.”

Maybe Leopold’s first calling wasn’t so far off after all. The best teachers are always passionate about what they’re teaching.