Canadian whisky is one of four recognizable global whisky styles. In all, more than 17.5 million 9-litre cases are sold annually in 160-plus countries, and it is the second best-selling whisky in America. One brand alone — Crown Royal — is the twelfth best-selling whisky of all kinds worldwide. Given what we know about how Irish, Scottish and American whisky making began, it’s natural, though incorrect, to assume a similar story for Canada. To understand Canadian whisky, we should begin by dispelling a few misunderstandings about how it came to be.

First, Canada distinguishes itself from other whisky-producing nations in that whisky making did not arise organically with early settlers and their tiny stills. Instead, it arrived in Canada as a vanguard of an already mature industry, in search of new markets. There was no need to reinvent that wheel. Instead, well-financed entrepreneurs from Europe and the US replicated large profitable distilling enterprises from back home.

Canadian moonshiners operating in the background, as they still do today, did not evolve into commercial distilleries as happened in other nations. No, home-distillers with their “Betty Crocker” operations and “Easy-Bake” stills made no contribution to what became Canadian whisky. Their objective was drinkable alcohol, and they fermented whatever source of sugar was at hand.

Second, it hampers our understanding to assume there is a single “Canadian way” to make whisky. Today, eight legacy distilleries make roughly 99% of all Canadian whisky, and each distillery follows its own practices. While they all make blended whisky, that’s not so different from how blended Scotch, Irish or American whisky is made. In all four countries robust flavoring whiskies are mingled with mass-produced, column distilled whiskies or spirits.

The Pioneer Period

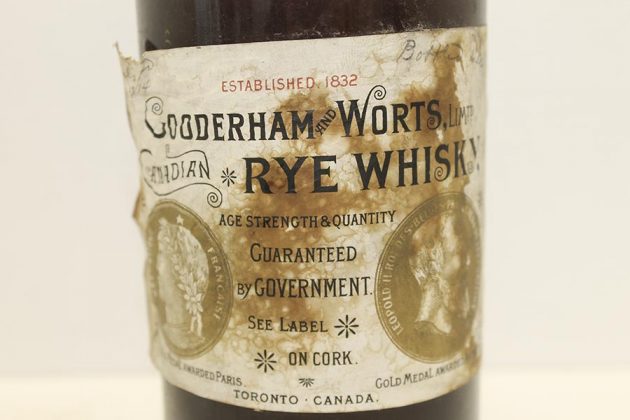

As in hockey, Canada’s whisky game developed across three exciting periods. Events in each period determined where Canadian whisky is today and foreshadow where it may go next. Canadians began distilling in a Pioneer Period, which began in 1786 in Quebec City. There, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, James Grant operated Canada’s first recorded still. Accordingly, many writers have dutifully credited Grant as Canada’s first whisky distiller. But Grant did not make whisky. Instead, he used inexpensive Caribbean molasses to make potable alcohol that was more a proto rum. Whisky making waited until settlers reached Montreal and then moved into Ontario where molasses was costly, but wheat (not rye) was plentiful and cheap. It’s another misconception that early Canadian whisky came primarily from rye grain. Really it was wheat whisky flavored with small amounts of rye.

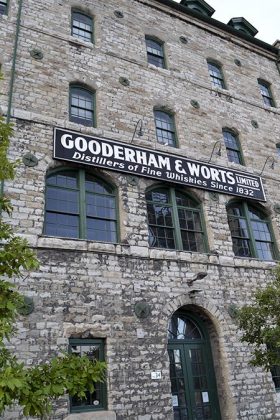

The Pioneer Period was a time of significant colonial expansion as dozens of towns, each with at least one commercial distillery, dotted what would become Ontario. Sadly, most are forgotten. The few names that remain today are simply Pioneer Period brands revived by new distilleries in new locations. When one of these pioneers, Charles Payne, sold his early proto-whisky distillery in Prescott, Ontario, to American cattleman JP Wiser, it was not so much for whisky but to make animal feed, with whisky as a profitable co-product. Wiser’s distillery did not long survive his death, and his brands moved to the Corby Distillery. Of all the Pioneer Period distilleries, the sole survivors are Windsor’s Hiram Walker & Sons, the facades of Toronto’s Gooderham & Worts and shells of Seagram’s in Kitchener.

Neither Canada’s distillers nor its regulators ever established a strategic alliance or plan to develop a distinct Canadian whisky style. However, an unanticipated consequence of a single event set Canada well on its way to distinguishing itself from other whisky-making nations. In 1887, the government introduced a regulation, to be fully implemented by 1890, requiring whisky be aged for a minimum of two years (now increased to three). Any impact this might have on the quality of the whisky was not even a remote consideration. Many commercial distillers already matured their whisky far longer than that.

Instead, the purpose was to put small distillers — those most likely to evade taxation — out of business. It was a successful strategy and one which distillers with stocks of aged whisky seized on. Canny producers quickly spun this as the government certifying that their whisky had been matured naturally. What was a tax grab for the government became a marketing coup and defining moment for Canadian whisky. In 1890, Canada’s was the lone government to require this.

Prohibition and Beyond

The second period, Prohibition and Beyond, began with a great shakeout caused by American Prohibition. Contrary to popular belief, these were tough times for Canadian distillers and just two from this period remain, with only one in its original location. America was Canada’s primary customer, and Prohibition decimated that market. Plummeting whisky sales allowed rum-running entrepreneur Harry Hatch to buy Hiram Walker, Gooderham & Worts and Corby distilleries at fire-sale prices. Eventually, he closed all but Hiram Walker, where he and his heirs consolidated production.

At the same time, Montreal’s Distiller’s Corporation Limited, led by Sam Bronfman, purchased the failing Seagram’s Distillery. It was an auspicious step for Canadian whisky. Mr. Sam, as he was known, was obsessed with quality and many of the innovations we now think of as the Canadian way of making whisky were his ideas.

At one time, it was common practice for Scottish, Irish, American and Canadian whisky makers to use non-whisky flavoring and coloring to make their whiskies more palatable. By the time American Prohibition ended, this practice had pretty much disappeared, though many, often in less overt ways, still do. Although documentary evidence is scant, many fingers (including those of former distillery workers) point to Mr. Sam as the instigator who eventually convinced the Canadian government to allow 9.09% of mature foreign spirits be added to Canadian whisky. This regulation was intended solely to make inexpensive “pipeline” whisky competitive in the lucrative US market. By openly adding American spirits to their whisky, Canadian distillers attracted favorable US tax rates, which kept prices low. Careful blending made any effect on the flavor undetectable, as domestic versions of the same whiskies remained untouched.

When American Prohibition ended in 1933, Canadian whisky became a hot commodity again, and more than a dozen new distilleries sprang up across the country. The euphoria, though, was short-lived. Palates were changing and consumers began favoring liqueurs and lighter spirits, particularly vodka. In 1972, Larry McGuinness Jr. of McGuinness Distillery in Toronto recalled having anticipated the trend to lighter whiskies, based on his success with lighter rums. By the mid-1960s he was producing lighter Canadian whiskies just as Scottish, Irish and American distillers were doing. Other Canadian distillers soon followed suit.

Light whisky helped keep all four nations in production, but it could not stem the tide, and each began losing distilleries as stocks of unsold mature whisky continued to grow. From nearly two dozen sizeable commercial-scale distilleries in the early 1970s, today Canada has eight. Until recently, these distilleries were content to fill the pipeline with light, inexpensive mixing whiskies. This has left many people with the erroneous belief that Canadian whisky has always been lighter than other styles.

As connoisseurs’ attention turned to single malt Scotch in the 1990s, they tended to forget about lighter blended Scotch. Similarly, the bourbon revival of the past two decades caused many to forget that until recently, American blended whisky was that country’s most popular style. Seagram’s 7 still sells over 3 million cases a year. And no one remembered that Canadian whisky could also be richly flavorful until John K. Hall bought the Rieder distillery in 1992 and turned it into Forty Creek, a Canadian whisky phenomenon. In so doing, Hall launched the third period of Canadian whisky, the Craft Period.

The Craft Period

When Still Waters Distillery opened in 2009, Canada officially joined a craft whisky movement that had been growing in America since the late 1990s. A few others preceded Still Waters, most notably Glenora (Glen Breton), founded in 1990 in Nova Scotia, and eau-de-vie distiller, Otto Rieder as far back as 1972. The craft image barely fits Forty Creek now that it has become a Canadian whisky powerhouse attracting the wallet of Italy’s Gruppo Campari, who paid $186 million for the distillery in 2015.

Today’s microdistilling movement was influenced more by events in America than anything happening exclusively in Canada. However, with Forty Creek, Hall put Canadian whisky back on the connoisseur’s radar simply by making its whisky just a little bit bolder than its competitors’ in the same price bracket. In addition, one-off, high-end special releases brought thousands of enthusiasts to the distillery for a celebration each year and to nab their bottle. In short, Hall made Canadian whisky neat again, opening the door for upscale Canadian craft whisky and for legacy distillers to premiumize their brands.

Among Canada’s 250+ microdistilleries, at least 75 now have whisky in bottles or barrels. Canada’s microdistilling industry is just a decade old, and already, at least a dozen new distilleries promise to nudge Canadian whisky towards its big flavorful past. Some of those pushing the flavor envelope include:

Yukon Brewers

Revenue from their brewery allowed Yukon Brewers to wait 7 years before releasing their whisky on the Two Brewers label. It simply bursts with flavour, and as each is blended from malt whisky made with differing mash recipes, each is distinctive. Already, influential enthusiasts speak of Two Brewers in glowing terms.

Shelter Point

Shelter Point started out to make single malt whisky and cracked that code pretty quickly with some very well-received releases. Before long, it also had Irish-style pure pot whisky in barrels, all made from barley grown on its 400-acre farm.

Still Waters

It began, like so many others, with single malt whisky, but Still Waters has made a more lasting impact with 100% rye-grain whisky released on its Stalk & Barrel label. New depths of flavor in the citrus/cereal regions take rye whisky in a scrumptious new direction beyond spices and oak.

Last Mountain

Last Mountain crafts big, soft, succulent whiskies from local Saskatchewan wheat. Of the legacy distilleries, only Highwood has much wheat whisky on hand. Last Mountain’s success will likely push others to try it.

North of 7

With the acclaim given Canada’s blended whiskies, it is a puzzle that the new wave of microdistillers focused on making single malts. Refreshingly, Ottawa’s North of 7 takes the mixed mash bill approach of American bourbon and rye. Its remarkably rich and healthily mature whiskies add new notes to Canada’s whisky flavor palette.

Dillon’s

Remember those aging requirements? Because of them, Dillon’s white rye is not considered whisky in Canada. But with three years in barrels, it joins Stalk & Barrel in exploring new flavor vistas for rye whisky.

Eau Claire

Caitlin Quinn’s Heriot-Watt degree in brewing and distilling is proving its worth as Eau Claire builds a steady following among whisky drinkers in the know — not only with its whiskies, but with novel and seasonal gins.

Central City

The best distiller’s malt, though packed with enzymes, is shrivelled and meager in alcohol output. Instead, Central City uses flavorful, plump, starch-rich brewers malts in an ever-expanding range of top-notch whiskies, each an experiment in flavor.

Sheringham

This distillery founded by an accomplished chef employs heritage grains in its search for balance and flavor. Its spin on Red Fife wheat already has whisky lovers taking notice.

Fils du Roy

Fils du Roy distillery raises terroir to a new level. Smoking barley malt and rye with peat from its own property, Fils du Roy creates whisky in a style that is decidedly not Scotch single malt.

Small, 19th-century distillers were less than a footnote to Canada’s whisky story, making the Craft Period – now – the first-time small distillers have a real opportunity to influence Canada’s whisky palate. Finally, in the third period, these rookies have a breakaway chance to take Canada’s whisky game into overtime.