In the world of distillation, there are a number of spirits that have a reputation for being rustic, unrefined and raw. Examples include crude fruit or cane spirits often known generically as aguardiente or aguardente in Spain, Portugal and their former colonies, fruit brandies called rakia in the Balkan lands and an agave spirit called raicilla from the Puerto Vallarta area of Mexico.

While these ungenteel spirits may or may not be illicitly produced, they are usually considered to be the alcoholic drink of the common folk. They are often produced using traditional, artisanal methods, though not always. Many such spirits have complicated histories in which consumption distinguishes social boundaries and classes and fosters local pride, where production is a source of economic empowerment for the disenfranchised and where their use in religious ritual causes the arbitrary border between the sacred and profane to become temporarily blurred. Perhaps no spirit exemplifies these traits more than clairin, the native rustic cane spirit of Haiti.

On a hot, sticky morning last November, I flew to Port-au-Prince, Haiti, to work with a new client to help him formulate a spiced rum and to lay down some non-spiced rum for long-term maturation in ex-bourbon barrels. When he and his father picked me up from the airport, we began a harrowing, three-hour journey north via a pockmarked highway to the small town of Liancourt, where his distillery is located. Once there, the plan was to use a locally produced clairin as the base for the two products. Little did I know that this would be a consulting job unlike any other that I have ever experienced. I would soon be delving into the deep world of clairin, as it is a symbol for the myriad social complexities of Haitian culture.

The history of clairin, and its accompanying social implications, has its roots in the three-tiered social structure that was imposed by the French during Haiti’s colonial period. The top of the social ladder was the white elite, followed by freedmen, who were the descendants of slave owners and black African slaves, with slaves constituting the bottom layer. With the slave rebellion of 1791, that social structure changed. Gone was the white French ruling class and its plantation system, with the mulatto freedmen taking their place in the new upper classes. The source of their power came through turning away from agriculture—as land had been distributed to former slaves—to more urbane pursuits in politics, business and professions such as law or medicine. Over time, the military also became a way that disadvantaged dark-skinned Haitians could move up in the world. These two upper-middle-to-upper-class societies have held an uneasy alliance for many generations.

Even as a middle class arose during the 20th century, the urban elite continued to promote French norms and culture—such as French language and the practice of Roman Catholicism—and light skin helped guarantee a favored place in Haitian society. In contradistinction to this was the peasant class, many of whom practiced Vodou, or “Voodoo,” a syncretic religion based upon traditional West African belief systems brought with the slaves, Roman Catholicism and the Taino religion of the native Haitians.

Even as a middle class arose during the 20th century, the urban elite continued to promote French norms and culture—such as French language and the practice of Roman Catholicism—and light skin helped guarantee a favored place in Haitian society. In contradistinction to this was the peasant class, many of whom practiced Vodou, or “Voodoo,” a syncretic religion based upon traditional West African belief systems brought with the slaves, Roman Catholicism and the Taino religion of the native Haitians.

More often than not, Vodou practitioners hail from peasant classes, speak Creole rather than French, are darker-skinned and tend to reside in the countryside. They also frequently use clairin as a spiritual libation in religious rituals.

Thus, as my client Jerel Registre, an American whose father’s family has deep roots in Haiti, explains, these traditional, rigid social structures and norms are still very much in place today although the boundaries are sometimes blurred. And among the middle class and the affluent French-speaking people in Haiti, consumption of clairin is frowned upon, as it is an indicator of the poor and disenfranchised. Registre observes that it is considered a “farmer’s drink,” as it is often consumed at a low-alcohol strength of 22% ABV and served with sugar cane as a rural breakfast. It also has strong associations with Vodou, which many traditional Roman Catholics and Protestants see as a diabolical form of spirituality. Rather, the upper classes prefer to drink “rhum,” with Rhum Barbancourt being the drink of choice and a source of national pride.

Thus, even though the distillate that is used as the base for Registre’s spiced rum is technically clairin, within this social backdrop it is clear why he refers to it as “rhum” on the labels of the bottle. Generally, rum gains more respect than clairin, as it is automatically assumed to be a high-quality distillate. It is also a more expensive product and will generate greater sales for the distillery than a product under the name of clairin ever could.

Yet, even with such social assumptions that it is an inferior spirit, the quality of clairin can be quite high. Among the rural and farmer classes, Registre explains, clairin production is a source of pride as well as a means of economic empowerment. It is also used in non-Vodou rituals and ceremonies, such as family reunions, where a small portion is poured onto the ground as a way to thank the sacred ground of Mother Haiti for tying a family together. In light of these things, its contradictory social and cultural meanings clearly are much

more complicated than a cursory view might show.

But if Rhum Civil, Registre’s spiced sugar cane spirit, can be called rum, then is there really a difference between clairin and rum in the production process?

This is also where things get tricky, although there do appear to be some clear differences.

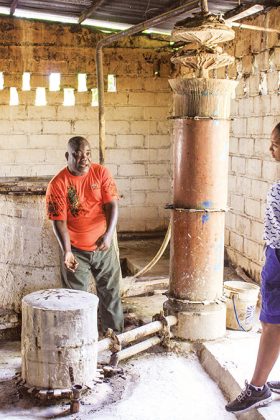

During my visit, Registre took me to a rustic clairin distillery deep in the interior of northern Haiti. Although he is not currently sourcing his distillate from “Lapia’s house” (the distillery has no formal name), he assured me that the production set-up is very much like most other traditional clairin distilleries, including the one where he is currently sourcing his distillate. In the future, he wishes to source some of his spirit at Lapia’s house.

In a distillery such as this, raw cane juice is first dehydrated over a fire that uses bagasse, or fibrous matter that remains after the juice is pressed from the cane stalks. This will help give the clairin a characteristic smoky flavor and aroma. When the distiller is ready to use the juice, it is rehydrated and will spend the next couple of weeks fermenting with only ambient native yeasts.

Once fermentation is complete, it undergoes a single distillation on a pot still with a crude column, capturing the distillate roughly around 55 to 58% ABV. The pot and column still at Lapia’s house is over 80 years old and before coming to this particular location, has been used to make clairin for several generations. There are some unique aspects of such a still. First, the fermented cane juice is poured into a long trough or pipe, where the fermented cane “wine” will seep through a basket and into a wooden chauffe de vin. This acts as a preheater before being released into the pot, which is directly heated using bagasse as fuel. This is another part in the production system where the characteristic smoky aromas of clairin are captured.

After vapor migrates from the pot to the column, it then travels in liquid form through coils in the chauffe de vin, which now acts as a condenser. After it exits from there, it will go through a second condenser contained in a concrete base, before it makes its appearance on the other end as newly formed clairin. The final distillate is smoky, with intense vegetal and herbal aromas of grass, mint, tarragon and tropical fruit.

Registre tells me that he ultimately would like for his spirit to be more refined through double distillation, capturing it at around 65% ABV. However, the local clairin producers do not seem to understand this concept, and it is unclear whether the miscommunication is one of language or a genuine lack of knowledge of how to produce a spirit of higher alcohol concentration. It seems, he tells me, that they also are afraid to produce a higher degree of alcohol off of their stills. However, by doing this, the distillate would now be a true “rhum.”

Even though Registre looks forward to the day when the spirit is a genuine rhum, the clairin distillate he is using now as the base for his spiced rum is a truly remarkable spirit. To me, the clairin is reminiscent of a high-quality artisanal mezcal, in both the care with which it is made and its smoky and earthy character. At roughly 55% ABV, it has the sort of congener, fatty acid content and overall body that lend themselves to long-term maturation. While it is clearly not a “refined” spirit, clairin, with its rustic unruly charm, truly embodies the spirit of Haiti.