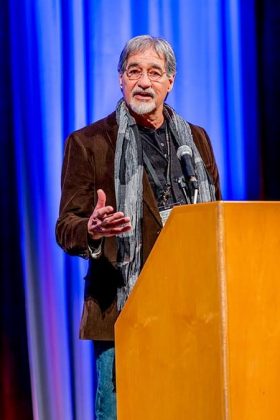

Duncan Holaday is pretty sure he’s diagnosed what ails many ADI members. It’s an affliction whose symp-toms include the conscription of every household vase and pot as a fermenta-tion vessel and spouses hollering down the cellar stairs to ask why their pressure cooker now has a hole it. Holaday has seen this affliction arise and spread, but he holds back on the impulse to inter-vene. He calls it “Distiller-itis.”

“I watch and I let it happen,” he said. “These people are trying to solve an impos-sible problem—like writing a great opera or solving a Rubik’s Cube in 10 dimen-sions. I watch because this is the source of what we are now calling craft distilling.”

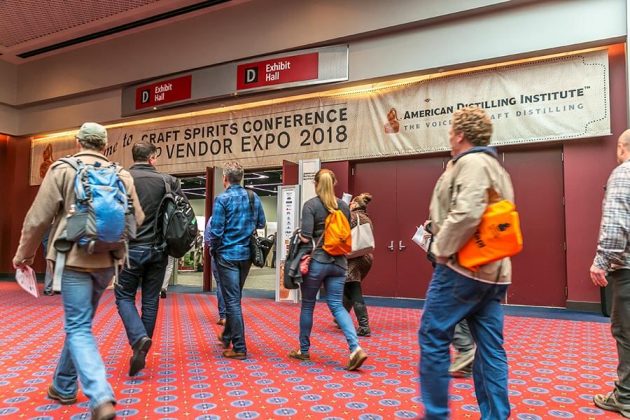

Holaday, a co-founder of Vermont Spirits and Dunc’s Idea Mill, was one of several to offer opening remarks at the 15th annual American Distilling Institute conference, held March 27–28 in Portland, Oregon. Nearly 2,000 attendees came to Portland to learn about the state of distilling from a host of speakers and 180 vendors offering up everything from bottling lines to turnkey still operations.

In his keynote, Tad Seestedt of Ransom Spirits in Oregon, hailed the successes of the industry and noted some of the advantages that have surfaced since he launched his distillery in 1997. Among them, the reduction on the federal excise tax that passed last year and, more broadly, the rise of social media, which offers a low-cost platform that allows distillers to be as creative with their messages as they are with their spirits and the ability to reach thousands of potential customers at a fraction of the cost of paid advertising.

But Seestedt added that the changing economic (and social) landscape for spirits was a consistent challenge. “That mentality of Prohibition still exists,” and spirits tend to be demonized more than wine and beer, manifesting in far more paperwork for producers of the former than the latter. (Ransom Spirits also has a winery, so Seestedt knows from paperwork.)

Liquor distribution is increasingly cen-tralized, meaning that it’s harder for the smaller distributors—who tend to be more attuned to the needs of craft dis-tillers—to raise their voices above the big-marketing thunder. And more com-mon pay-to-play stipulations (sellers of liquor illegally requesting payments or goods in order to stock products) have presented another hurdle for small pro-ducers, Seestedt said.

“Craft spirits as an industry is here to stay,” he said. But he urged the industry to continue to work together to ensure that legislation and market structures championed by the larger, legacy brands don’t steamroll craft. “If we don’t advo-cate for the change that we want, it is likely that we will get the change we do not want,” he said.

Among other themes explored over the course of two days were passion vs. prac-ticality, and tradition vs. innovation. And all this was set against the background of a booming industry fueled partly by entrepreneurs looking to hop on a train that’s picking up speed as it continues to leave the station.

In the opening session, Michael Kinstlick, CEO of Coppersea Distilling, also provided a snapshot of craft dis-tilling today, as he has done every year since 2011. The upshot: New DSPs are now registering at a pace of two for every working day, suggesting a crowded field that shows little sign of thinning. While not all DSPs will go on to produce spir-its—some are reserving their options forpossible future operations that don’t come to fruition—Kinstlick’s analysis of data from the federal government and the listings in the ADI directory concluded that 1,400 distilleries are now producing spirits in the United States—up from 234 seven years ago.

While that’s clearly significant growth, Kinstlick provided some intriguing context: the larger, legacy distilleries have also grown rapidly in recently years, with many expand-ing to meet demand. The capacity they have added is more than three times the produc-tion of all current craft distilleries combined.

So are distillers facing a “Craftpocalypse?” Kinstlick thinks not. He estimates that craft spirits now account for merely 1.75 percent of the spirits market, far below the 12–15 percent market share captured by craft beer, another industry that has seen stunning expansion. There’s still room to grow.

How distillers walk the line between tra-dition and innovation was another topic frequently touched upon in conference ses-sions. Spirits producers don’t want to stray too far from hallowed traditions, which could confound consumers. But major pro-ducers also claim tradition, often with a bet-ter argument, as many have been distilling for decades if not centuries. Legacy produc-ers also have the advantage of vast econo-mies of scale, outsized marketing budgets and virtual control of distribution channels.

How can the Davids of craft compete with the Goliaths of industry? A number of distillers argued that innovation and nim-bleness—of advancing deftly into the future without losing sight of the past—may help the small producers succeed in the long run.

In her “Sweet Talk: Sugar in Spirits” session, Lauren Patz of Spirit Works in Sebastopol, CA., laid out the hows and whys of TTB regulations involving alcohol content and sugar. But she also encouraged more experimentation in liqueurs in partic-ular. (“Anybody else making anything with honey?”) It’s a category that’s been hide-bound and perceived by consumers as being overly syrupy and sweet. “We can make something special and revitalize liqueurs,” she said.

Chip Tate of Tate & Co. Distillery in Waco, Texas, encouraged attendees at his session, “Stills & Whisky, Ways & Means,” to pay closer attention to the past when designing stills for tomorrow. Tate, who constructs and hand-hammers his own copper stills, could have been addressing an 18th-cen-tury distillers guild as he explored the subtle differences that result from varying the angles of lyne arms and how the shape of onion heads can determine how much flavor is captured and created. “Batch dis-tillation produces a significantly different spirit character compared to continuous still because of the turbulence effect,” he noted. Embracing these technologies of the past can help position craft producers to compete with big-industry distillers.

Another panel that touched on the issue of innovation looked at the newly expanding category of American single malt whiskey—at least 80 distillers are now producing whiskey from barley and many are faced with retailers confused about how to categorize it. Christian Krogstad of House Spirits, makers of Westward Single Malt, noted that Total Wine & More has recently agreed to pro-vide single malts with their own shelves, and not mix it in among Scotches and bourbons as many sellers have done in the past. The panel also looked at recent efforts to create an official TTB category to help better define American single malts in the minds of consumers and retailers.

The panel where traditional and modern butted heads most directly was no doubt the panel on accelerated aging, with six panelists looking at new technologies—such as high-intensity light and ultrason-ics applied to a combination of wood and spirits—that have been increasingly used to create more mature spirits in a shorter amount of time. Several panelists seemed a bit uncomfortable with the term “rapid aging”—Earl Hewlette, CEO of South Carolina-based Terressentia Corp., pre-ferred “fast filtration”; Gary Spedding, of Brewing and Distilling Analytical Services in Kentucky, leaned toward “fast maturation.”

But most panelists concurred that the craft industry would likely benefit from welcoming innovations such as these, even if it meant a break with tradition. After all, it was noted, the column still was once a radical and controversial advance in distillation. After two centu-ries, it’s now tradition.

Bryan Davis, founder of Lost Spirits in Los Angeles and a pioneer in manipulat-ing spirits aging through heat and light, likened traditional distillation to French cooking—just because molecular gas-tronomists came along a decade ago and took a traditional cuisine in new direc-tions didn’t mean that consumers aban-doned traditional French cooking. It was just adding a new approach to the canon.

Not all were buying the French cook-ing analogy. “I think it’s more like McDonald’s—which I happen to think is delicious,” said audience member and alembic distiller Dan Farber of Osocalis Distilling in California.

Another in the audience asked if new terminology was now needed to distin-guish speed-aged from traditionally aged, especially if the flavor profiles contin-ued to narrow. Little consensus emerged on this point, but John Foster of West Virginia’s Smooth Ambler noted that “the problem with a perfect forgery is that it is still a forgery.” He went on to add that someone could learn to copy a John Coltrane song note for note. “But: You haven’t learned to play like Coltrane. You’ve learned to sound like Coltrane.”

If there was one underlying theme across the panels and workshops, it was passion for the craft. “What we have is passion and drive and that can be harnessed to do incredible things,” Seestedt said.

Holaday also hailed that “affliction” that drove distillers to continually tin-ker and tweak. “Most of the time these inventions don’t work,” he said. “But it’s at these moments of exuberance, of trying anything and everything, that the seed is planted, the germ gets in and grows and spreads. And sometimes the result is beautiful.”

“The real reward for sufferers comes when friends, family, significant others, customers, bartenders and other distill-ers become fans of your work,” he added. “Fans—not brands—are what drive the craft-distilling industry.”