Distiller interviews Goat Rodeo Capital venture capitalist Carlton Fowler, the beverage industry’s poster boy for the one investing ratio that really matters: LTV/CAC

Distiller interviews Goat Rodeo Capital venture capitalist Carlton Fowler, the beverage industry’s poster boy for the one investing ratio that really matters: LTV/CAC

Are craft spirits really a hot investment category? Or do venture capitalists just want something good to drink? After all, it’s worth remembering that America’s original distilling VC went belly up.

After prohibition ended in 1933, Joseph L. Beam, “Mr. Joe” to his friends and family, invested $9,000 (about $165,000 in today’s money) to relaunch Louisville’s A. Ph. Distillery, renamed Heaven Hill. Then Mr. Joe promptly ran out of capital, and unwittingly became distilling’s first failed VC. While Mr. Joe went down in flames, the story had a happier ending for the opportunistic Shapira Brothers. They jumped in with $20,000 and became the big winners in the Beam fortune.

Big beverage players know how to invest capital to build spirit brands because they understand one super-important formula: LTV/CAC. LTV is the Long Term Value of a customer. And CAC is Cost to Acquire a Customer. The reason why this formula is so critical is simple: If you can acquire the long-term brand loyalty of a repeat customer at relatively low cost, you have made a marvelously good investment. The rule of thumb in technology investing is that if your brand’s LTV/CAC is over 4:1, you’re golden, and in some cases even 2:1 is ok. In spirits, a good brand can hit 10:1, and a great brand, 40:1. That means that you’re investing $1 and getting $30 back over the next few years. That’s catnip for capitalists.

No wonder the big boys are investing heavily in new brands. Constellation Brands has their $100 million fund, especially interested in female and minority-led spirits ventures to address new markets. Diageo’s UK-based Distill Ventures has backed ten spirits projects since 2013, and bought George Clooney-backed Casamigos Tequila for a $700 million in 2017, and Ryan Reynolds-backed Aviation Gin for $610 million in August, 2020. Gallo invested nine figures in its New Amsterdam Gin and Vodka, which quickly became the fastest-ever zero to hero brand. Then Gallo did it again with High Noon, which surpassed even New Amsterdam’s extraordinary results. Big money guys like Chris Hollod, actor Ashton Kutcher, First Beverage Group (Drizly) and Winklevoss Capital (Partender and Minibar) are also in the spirits and RTD game, all seeking giant-sized LTV/CAC.

And while the big guys are investing, and hardy souls such as Alumni Ventures are backing celebrity brands such as Bob Dylan’s Heaven’s Door Whiskey, spirit-focused VCs are a rare breed. The reasons why are easy to understand. Many VC funds have “vice” clauses in their limited partner investment agreements which keep them away from cannabis, booze, tobacco, guns, prostitution, and porn. And the other is the perceived super-riskiness of spirits businesses. Crunchbase reports that for two-thirds of a sample of 1,100 VC-backed technology companies raised a seed round and then flamed out — complete failure. And only 2% reached valuations of $500 million or more. For spirit and beverage ventures, the numbers are even worse.

That’s why Distiller is really interested in why Carlton Fowler and Goat Rodeo Capital are so gung-ho. After graduating from UC Berkeley in Political Science, Fowler started in booze-themed real estate with the Rum Point Club residences in the Cayman Islands, then got an MBA from the University of Michigan. Armed with his Ross School sheepskin, he went from developing buildings to five years building brands at E. & J. Gallo Winery, reporting directly to CEO Ernest Gallo himself.

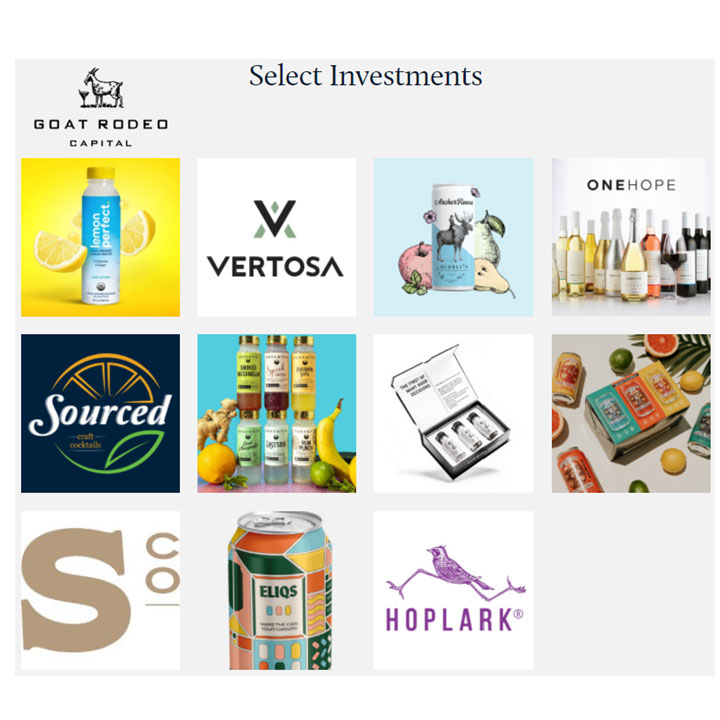

Then, as so often happens in Silicon Valley, Fowler caught the startup bug, founding student loan repayment innovator Pickpocket, and beverage startups Granter Drinks and sPacific Gravity. By 2019, Fowler decided it was time to try his hand at venture capital with Goat Rodeo Capital.

The firm’s name comes from Fowler’s observation that “any promising early stage company has one or two things that they do really well, a strong vision, and the rest is usually a goat rodeo.” After being introduced by Industry Collective super-connector Taylor Foxman (Taylor@IndustryCollective.org), Distiller caught up with Fowler via Zoom.

Distiller: That’s the origin of your focus on beverage brands?

Fowler: Sometimes is better to be lucky than good, and my first day at Gallo they handed me a plane ticket and said “Since you’re the new innovation guy, today you’re flying with Ernest {Gallo, the wine giant CEO] to Chicago,” I made a good first impression apparently. Ernest knows that Gallo is the largest winery in the world, and thought why can’t we also be among the biggest spirits guys? The results of that focus are mega-brands New Amsterdam, New Haven, and High Noon. RTD is a megatrend, something real, something new, and High Noon is an allusion to the sun at its apex.

Distiller: So what’s Goat Rodeo’s sweet spot investment?

Fowler: I left Gallo to start the fund based on what I had learned about how brands go out and make their way in the world. I’m trying to share these lessons to new brands. We focus on seed and Series A, before the mistakes are made so they can benefit for what I’ve done wrong. We are not only a spirits VC, we also touch traditional bev and cannabis. Alcohol as an investment category keeps lots of VCs with vice clauses out. It’s also wonderfully expressive. For example, I’ve never tapped anyone on the shoulder and told them what toothpaste or software I use, but I have with alcohol. It’s so evangelistic, and expressive of personal attributes, that I love it.

Distiller: Who are your competitors?

Fowler: It’s more collaborative in VC than competitive. We are often joined by other VCs in our investments. Corporate investors have a different orientation from VCs. They want to acquire brands and bring them into their ecosystem, and have rights of first refusal clauses [ROFRs] which often destroy value for companies. By contrast, I’m trying to get return for my investors and have a great time. There are no ROFRs in Goat Rodeo money. Our limited partners have invested low eight figures in our fund. When we invest, we can go from Seed to Series B. We start to get real conviction behind an investment when we hit $2 million in. Seed are usually smaller than that, and we allocate for later follow-on investment [for when the company gets consumer traction]. Most VC returns come from a small number of investments. Big VC funds like Sequoia have a lot of investing generalists. I’m a specific interest guy. I know one thing really well. That means I can often get into a deal with a smaller number of dollars because of the access I offer to beverage-specific resources.

Distiller: What about this trend of celebrity-backed spirits brands, like Clooney and Reynolds and Dylan?

Fowler: Even though [Hunger Games and 30 Rock actress] Elizabeth Banks is an investor, I’m not a believer in pure celebrity. I’m a believer in awareness to build brands. Today’s brands are not all just built on a premise. Brand-building is being re-thought. I’m doing a [Building the Next Alcohol Brand] panel at the Consumer Goods Summit [November 16-18, 2021]. And some of these brands are being built in completely new and previously unpredictable ways. At ADI conference I first met Joe Heron, and he’s the perfect example of someone who’s thinking about the consumer. He got great exits in cider [Crispin Cider], Nutrisoda and Copper & Kings American Brandy. I’ve got a friend in spirits who is super-disdainful of marketing to consumers. He’s stuck in the idea of being an artist, which is going to doom him to remaining undiscovered and poor. Without the consumer, there’s nobody to evangelize for it. I invest in things that are unique, and have consumers. And that’s the major difference. Consumer is not a bad word.

Distiller: What are forces that are going to drive the spirits business going forward?

Fowler: Remember that alcohol is 20-to-30 years behind all other consumer packaged goods [CPG]. What I mean is that the average penetration rate of ecommerce in CPG is 30%. For alcohol, it was 1% pre-COVID, now it’s 2%. Alcohol’s real problem is regulatory. Let me ask you, what is harder, getting a head of rapid-rotting lettuce from farm to store to your house for $4, or shipping an $85 shelf-stable bottle of WhistlePig Rye to your house, it’s the latter. That’s baffling. We’re a big fan of delivery services like ReserveBar, Speakeasy, Drizly, I love them. Remember the “attention-intention split.” Google is an example of intention, because you have to intentionally input a search, while Facebook is attention-based or passive because you get stuff fed to you. Intention means I want my specific brand and I’m willing to do what’s necessary to get it. Ecommerce is based on intention, and over time, intention always beats regulation. [Alcohol’s] 3-tiered system has a lot going for it, but ecommerce will smooth it out. That’s because anything that is convenient and new, can scale much faster. Scale is not a bad word. WhistlePig [which recently received a minority investment from luxury brand giant LVMH] started small and is now big. They are good entrepreneurs, who bought lots of Canadian rye before it got popular, and cultivated rye drinkers. At High West, they have proved that in grabbing consumer tastes, blending matters, and marketing good blending is a winning strategy [High West was bought by Constellation Brands].

Distiller: What are the success signals that you see in alcohol entrepreneurs today?

Fowler: The success standouts are Ryan Reynolds at Aviation Gin and George Clooney’s team at Casamigos. Very few understand why those buyout prices were so high. They get SaaS [the acronym for software-as-a-service, such as Salesforce, Adobe, Microsoft, Dropbox] valuations because of how high their customer loyalty is. Customer loyalty translates into high lifetime value [aka LTV]. LTV matters. When you focus on the consumer and product quality, you too can be a standout success, because that focus lowers your cost to acquire and keep a customer [aka CAC]. And it’s that ratio between LTV and CAC that really matter when it comes to valuation.

Distiller: And how about the worst mistakes?

Fowler: Recently I watched an entrepreneur pitching investment who only sold himself, and didn’t focus on pleasing the consumer. Needless to say, he got no money. Another mistake entrepreneurs make is focusing on valuation rather than how an investor can help, and how much you really need to get to the next level. Also, a high valuation can easily turn into a down round [a down round is investor-speak for when a company raises money at a high pre-money valuation, then has to raise more funds later at a lower valuation, resulting in giant dilution of founder equity value]. Remember, you can’t eat paper gains, the only thing that matters is the exit, or getting to be a healthy self-sustaining business.

Distiller: What are your two big pieces of advice for craft spirits entrepreneurs?

Fowler: I have a partner who has a saying “always be fundraising.” But my version is always make sure you’re leading with your passion. For craft brands, the [investor] check sizes that move the needle are smaller than you think. Don’t be afraid to share your passion on a plane when you’re sitting next to someone. Recently I witnessed someone describing their distillery to me at a restaurant, and a guy at an adjacent table overhead us, and came over and said he wants to invest. The second piece of advice is never stop thinking about your distribution. This is what dictates growth, always talk to your distributors and retailers and bars, from small to big. Keep in mind that most distributors think of themselves as a hammer that just pounds the big brands. And when you’re a hammer, everything looks like a nail. The only way to get them to focus on your customer value is to be very collaborative and understand what makes you unique and keeps you top of mind, and sell that. And sell it hard, because that’s what we’re here to do.

— Jay Whitehead is the editor of Distiller Magazine.