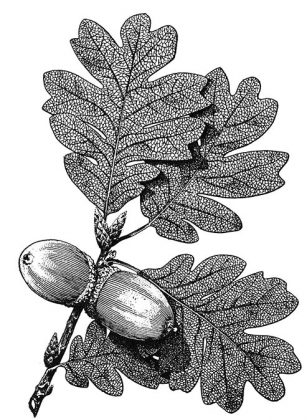

Oak first appeared on earth a little over 65 million years ago. Today, oak trees grow to maturity in the temperate zones, but many of the species are shrubs and quite unsuited to barrel production. There are more than 500 species of Quercus in the Northern Hemisphere alone, plus another 86 natural hybrids in the United States.

In the USA, two regions are the principal source of oak: the Ozarks and the Appalachian mountain chain, which has a history of depletion, then re-establishment, due to the level of rainfall during climate changes. These two regions represent a rich source of flavorful extractives and high oxidation potential. Quercus alba, commonly known as American oak, is the dominant white oak throughout the country. Other subspecies occur more frequently in other regions. For example, subspecies such as Quercus macrocarpa—the bur oak—is found in valley bottoms, and Quercus muehlenbergii—the chinkapin oak—occurs on well-drained slopes.

In France, the situation is quite different. French forests are managed by the Office National des Forêts (ONF). Two species, Quercus robur and Quercus petrae, are found in nearly equal proportions, although the former is becoming the more abundant. Since the beginning of the 20th century, forest inventories have been thriving

and expanding.

French production of oak has increased to 325,000 cubic yards, producing about 500,000 barrels of different sizes per year. Half of that is for export to different parts of the world.

Origins of the Oak Trees

The essence and the terroir of the oak are crucial for the aging of spirits. The grain tightness depends mainly on soil moisture retention, available soil nutrients and the density of the forests.

Quercus robur grows mainly in the rich soil of the Limousin forest, located in the center of France, and in parts of Russia. Being of large diameter, these trees offer large grain, which is more porous, resulting in faster extraction of wood compounds during the maturation process, and yielding complex structure and ample tannins.

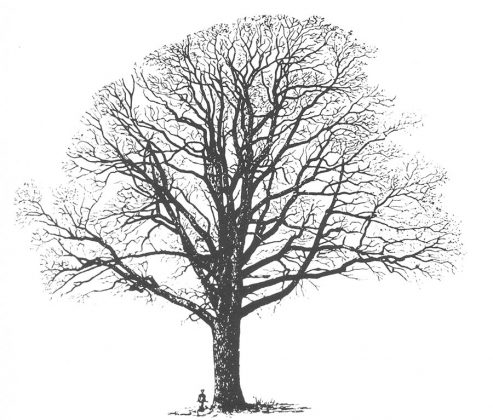

Quercus robur prefers deep fertile soils, deep loam and chalk. Full sunlight is crucial to its full development.

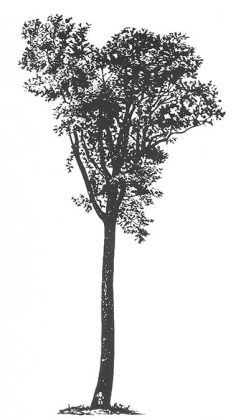

Quercus petraea, or sessile oak, grows in light, sandy, loamy and rocky soils. They tend to be lean and tall, with tight grain, so there is a slower extraction during the maturation of a spirit. The trees are taller, straighter and older due to close planting and the shadowy light of the forests. They take between 100 to 150 years to reach maturity and can be found in forests such as the Tronçais, Allier, Vosges, and in Eastern Europe.

Quercus alba tends to be less tannic than the European species and is quite rich in vanillins and lactones. They offer characteristic aromas of coconut and vanilla, bringing softness to distillates. Sometimes, an aroma of green olive is present when the staves are not air-dried long enough and the toastage is too light. New barrels are used primarily for bourbon and other American whiskeys, with the used barrels finding a secondary market for the aging of other brown spirits, such as Scotch, rum and tequila.

Tree growth is faster than its European counterparts, maturing in 60 to 80 years. Although the eastern two-thirds of the United States possesses Quercus alba, the best trees are grown in the Ozarks, where the growing conditions have rocky soils and thick undergrowth, producing more extracts compared to trees grown in northern climates or in the Deep South.

Oregon oak can be found from southern California to southwestern British Columbia. It does have a beautiful grain similar to European oak, but needs to be well seasoned, and attention should be paid to the straightness of the grain. Irregular grain can cause splitting and leaking; consequently, the staves should be thicker than with other American white oaks. Typical characteristics include savory spices and smoke.

French Forests

The oak forests of France are quite diversified in terms of soil conditions, microclimates, density of trees and locations in which they are found. Below is a partial list in alphabetic order, either by departments, regions or cities: Allier, Bercé, Bertrange, Bitche, Bretagne, Citeaux, Darney, Dordogne, Fontainebleau and Blois, Gers, Jupille, Jura, Montlezun and Monguilhem (Armagnac), Limousin, Nevers, Pyrenees, Troncais and Vosges forests.

The principal source for spirits with its wide-grained wood of around eight grains per inch.

Color—dark yellow

Growth—large, slow, with wide grains

Color—clear yellow

Growth—high, fast, with fine grain

Color—off white/cream

Growth—faster growth, fine grain

Armagnac

Two hundred years ago, the Armagnac region had 155 barrel makers; now, there are only three. Only 10% of the oak used in the Armagnac region comes from the local forests of Montlezun and Monguilhem, which grow black oak (Quercus silicus). The Limousin forests provide 85% of the oak, while 5% comes from other parts of France and Europe.

Cognac

About 70% of the staves used in Cognac barrels are wide-grained oak from the Limousin forests; the remaining 30% are fine-grained oak from the center of France—the Allier and Tronçais forests.

Barrels in America

A century ago, there were thousands of coopers in America. Now, only 25 barrel makers are in operation. However, there are now more than 1,000 craft distillers in the USA, compared to the early 1980s, when there were only five in production.

American whiskeys, with the exception of corn, have to be aged in new charred oak casks, resulting in a deficit of barrels for their production. There is even a shortage of barrels in the secondary market for used barrels.

The charring process for barrels imparts strong caramelized flavors from the wood sugar with an intense smoky character, creating powerful masking flavors. The other effect of charring is the disappearance of the terroir, or character coming from microclimates, air quality and minerals, which reduces complexity and upsets the balance.

These states and regions are the main sources of oak for barrels: Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, the Ozark Mountains, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Oregon and Wisconsin.

The American cooperage industry produces about 1 million barrels of 55-gallon capacity per year, most of which are destined for aging bourbon.

Japanese Oak (Quercus mongolica)

Mizunara oak has been used for the Japanese whiskey industry since the 1930s. The casks are highly prone to leaking and damage, since the oak is soft and very porous. As a consequence, the aging process has been modified; therefore, bourbon and sherry casks are now being used for maturation. The whiskeys are then transferred to mizunara barrels to gain their unique profile of flavors, such as vanilla, honey, flower blossoms, pear, apple, clove, nutmeg and spices, plus sandalwood and coconut aromas. In comparison with American oak, Japanese oak has slightly more “cis-oak” lactones, which are responsible for coconut aromas, and much more “trans-oak” lactones, resulting in stronger and more persistent aromas which are complementary to grain spirits.

Other Oak Regions

Russia Quercus sessilis is from the region of Adyghe near the Black Sea on the 45th parallel. It is very similar to the oak from the French forests of Allier and Tronçais in that it grows very tall with tight-grained oak. They also have Quercus robur, similar to the Limousin forests but the tannins are more intense than the French, with elegant and sweet aromas.

Poland Quercus sessilis has cardamom aromas.

Serbia & Hungary Quercus sessilis produces a wide variety of spice notes.

Italy Quercus frainetto, which is fine-grained with light tannins and lots of finesse

Bulgaria Quercus sessilis: The forests of the Southern Balkans produce mostly slow-growth sessile oak.

Spain Sessile oak from the northern region of Galicia

Czech/Moravian/Carpatian/Romanian Sessile oak