Blazing New Trails

The goal of Corsair Artisan is to make unique and innovative spirits. The motto is simple: If it has been done before, we don’t want to do it. Corsair also has a lofty vision: to expand the horizons of whiskey making. How can this be done? By making distinctive whiskeys no one else has ever made. Corsair has made a number of alternative whiskeys: ‘alt whiskeys.’ An alt whiskey is any whiskey made outside the norm. The distillery focuses mainly on three types: unusual grains, smoked whiskeys from something other than peat, and hopped whiskeys made from craft beer. With this goal in mind, Corsair began looking at all the smoke flavors that, to our knowledge, have not been used in whiskey making. The distillery has smoked rye whiskey, bourbon, malt whiskey, wheat whiskey, and whiskey made with unusual grains like amaranth. Corsair has even smoked vodka, agave spirit, rum, and gin. Corsair creates about 100 new recipes a year, and pairs them down until only a few actually become production whiskeys.

Why Craft Distillers Should Play with Fire…

When first trying to get Corsiar off the ground, we were obsessed with big smoky and peaty whiskeys from Islay. Corsair did not have access to peat in Tennessee but we had a lot of other great smoking materials. At the time, many craft distilleries were getting beat up because their whiskey was under-aged and tasted too young and hot. Worse still, some faux craft distillers were not even making their spirits but buying someone else’s bulk whiskey and bottling it as their own. Although high quality, this product was not distinctive from the big boys.

Corsair makes our whiskey and rarely gets beat up for it being too young. Why? Early on, the founders noticed an interesting trend in magazines, competitions, and whiskey judging.

In general, the older the whiskey, the higher it scores in reviews, but there is one area that this trend does not hold — Heavily-peated, or smoked, whiskeys score much higher than their age would belie, and they taste great. I personally prefer several of the less-mature, heavily-peated Islay malts to the older, yet minimally-peated, whiskeys. This realization prompted research into smoke and smoked whiskeys. It is an area where craft distilling could contribute to the world of whiskey, even with the hurdle of youth.

Very few craft distilleries are exploring smoked whiskeys. Many craft distillers focus on making Bourbon, which is great whiskey but unfortunately shows easily any flaws in fermentation and especially aging. Bourbon is probably the most difficult style for a new distillery to start with, unless they truly have time to let it mature.

Also, it appears that when consumers do not know specifically what they are looking for in whiskey, they focus on age. However, when presented with a smoked whiskey, consumers focus on the character and quality of the smoke, not the barrel. Corsair’s focus paid off in a big way when Triple Smoke whiskey (made with cherry wood, beechwood, and peat) won Whiskey Advocate’s “Artisan Whiskey of the Year”. I encourage young, aspiring distillers to experiment with smoke whenever possible.

American Whiskeys…where’s the smoke?

I first learned to distill at the Bruichladdich Distilling Academy, in Islay, Scotland, where there was lots of amazing Scotch with incredible smoke character. It begged the question why were there no smoked American whiskeys? I became determined to make an American smoked whiskey upon returning to the states.

Before the 19th Century and the invention of indirect kilning, all malt was smoked. Brewers and distillers burned whatever they had around, like peat, to dry malt for beer and whiskey. Whatever they burned left a smoky character on the final malt. The non-smoked malt was seen as being newer and superior — this, coupled with changing tastes meant there were no smoked American whiskeys. It still shocks me that no one in the South, where smoked meats like BBQ are everywhere, thought to make a smoked whiskey. Despite the abundance of hickory, oak, mesquite, cherry, and apple woods at their disposal, there are still only a handful of smoked whiskeys made by American craft distillers.

Smoke Flavor Goodness

Woods

Corsair has experimented with a number of alt smoked whiskeys using peat alternatives, most being made with wood. The smoked whiskeys are divided into five different categories: woods, barks, roots, herbs and used barrels. Wood flavors are broken up into several sub-categories. Fruit woods like apple, cherry, mulberry, pear, and nectarine have a distinct sweetness and exhibit some of the most pleasant smoke smells. People who generally don’t like smoked whiskeys will often try these. These whiskeys tend to be strong on the nose and body with a weaker finish. They usually gain balance when combined something else, like hickory, oak, alder, birch, ash, or mesquite. These traditional smoking woods create a great base character, but aren’t always the most distinctive on their own.

Nut woods — like almond, macadamia, black walnut, and pecan — stand out with nutty flavor but sometimes exhibit an acidic finish. Citrus woods — like lemon or orange wood — are some of the most unique flavors. They add intense tropical fruit, oily, and citrus smoke character. Citrus woods can dominate a whiskey and often lend gin-like properties, so they are best used in small amounts for blending.

Herbs, Bark and Roots

Native Americans would cut tobacco with herbs for flavor, religious and ceremonial purposes, which led us to experiment with herbs, barks, and roots. Herbs can be incredibly distinctive and full of character. Sage is one of the most distinctive. Barks are similar in flavor to wood, while roots have a very different flavor profile.

Barrel Woods

A distiller once asked if Corsair had ever smoked malt by burning whiskey barrels themselves. We liked this idea and immediately experimented with different types of barrels, naming this the oak category, as they are mostly made from the related wood species: Quercus Alba (American White Oak) and Quercus Robur (European Oak). Oak is a fantastic base smoke for building a whiskey. It boasts a strong body but is weak on the nose and finish. Oak is an amazing sponge, absorbing the flavors of whatever has been stored in it. Wine barrels add great character to the nose of the malt and final whiskey.

Tabasco©, is a Louisiana hot sauce that is oak-barrel aged for two years. Using a Tabasco barrel, the legendary character comes through in a smoked whiskey with a peppery nose and long, spicy finish.

Cabernet barrel French oak barrel, Bourbon barrel Tabasco © barrel

Grain Matters

Different grains pick up smoke character in differing degrees. The base grain has a strong effect on the mouth feel and perception of smoke flavors.

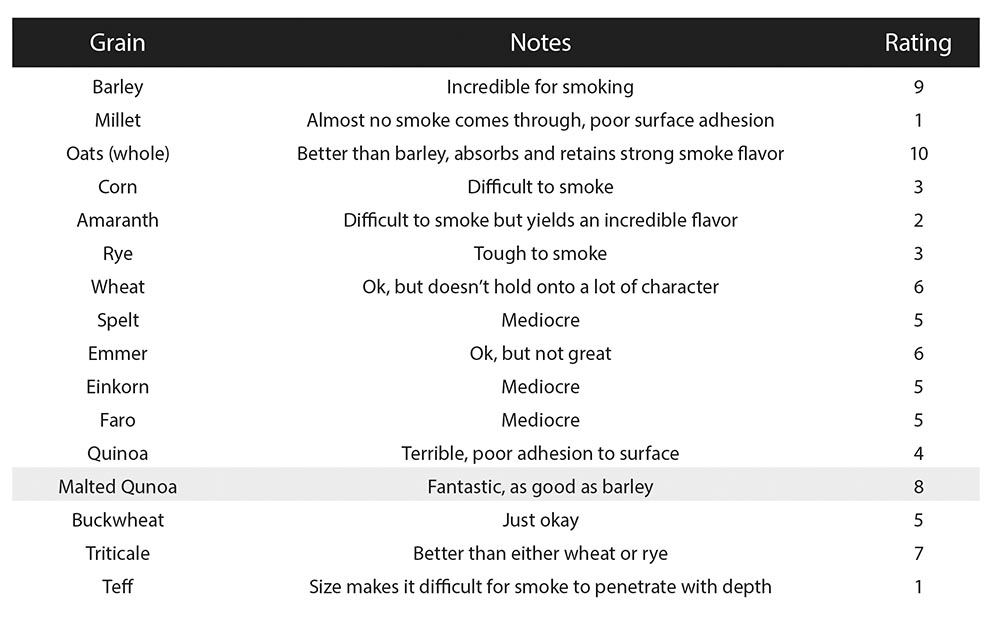

Barley is an amazing grain, especially for whiskey. Oats are as good or even better. Oats change and expand the mouthfeel of a whiskey and can be very useful when designing smoked-whiskey recipes. Malted quinoa (not unmalted) is nearly as good as barley. Similarly, quinoa changes the mouthfeel and finish, also adding nutty and earthy elements. (Chart below shows how different grains accept smoke; on a scale from 1 to 10, 1 being very difficult and 10 being very easily).

Smoking the Malt

Corsair focuses mostly on smoking malt, as this is the simplest and most common process. It can literally be done in a grill. Smoking can be done during malting or malt can be wetted and smoke finished. Chlorine-free water must be used because chlorine combines with smoke and creates nasty, off flavors. The grain must be fairly dry afterward to be milled. If the smoking temperature exceeds 170 degrees, the enzymes necessary for starch conversion will be destroyed and additional un-smoked malt must be added during brewing.

When malt is smoked, then distilled, the smoke flavor comes over in the distillate. This is a great, time-tested process, but labor-intensive and does not give the best yield of smoke flavor for the effort. Ninty nine percent of smoked whiskeys are flavored this way.

It is also easy to take grain that has already been malted and smoke it. The Bairds Malting Company in Scotland has said that rewetting pale malt and then smoking it can yield a very close approximation to standard smoked malt.

Malting from scratch and smoking during the kilning phase is difficult. There is a saying: “There are many homebrewers of beer, but very few home maltsters.” Malting is tricky, time consuming and tough to master — not everyone has the patience for it. But malting is the oldest technique for putting smoke in beer and whiskey, with centuries of tradition behind it. Floor malting doesn’t require specialized equipment, though on a large scale it’s quite complicated. If using a rare fuel source or expensive wood, this might not be the

best route.

Smoking other Spirit Types

In addition to whiskey, Corsair has subjected other types of spirits to smoke experiments, including gin and rum. For the gin, smoked botanicals were placed in the carter head of the still. The carter head makes a lighter and more floral gin with less of the heavy oils. It also lightens the smoke flavor to reveal fewer ashy, creosote, off-flavors. These spirits exhibited a more pleasant, “distant campfire” aroma.

Molasses based rum was matured in barrels that formerly contained a smoked whiskey. When first distilled, the spirit was rather unremarkable. After resting in the smoked barrels, the rum’s sweetness became a wonderful complement to

cherry wood.

Techniques for Smoking Whiskey

Imparting smoke into liquid is an easy and ancient process. We have experimented with a number of techniques for adding smoke to whiskey. These techniques, listed below, range from really simple to incredibly complex.

- Smoking the malt

- Creating liquid smoke and blending it with whiskey

- Smoking the barrels before filling

- Smoke injecting

- Surface transfer

- Surface agitation

- Carter Head

- Spray condensation

- Forced smoke distillation

Other Factors that Effect Smoking

There are many factors that influence smoking: the amount of time smoked, temperature, humidity, fuel source, type of smoker, cold or hot smoked, etc… One of the most counterintuitive is time.

Time

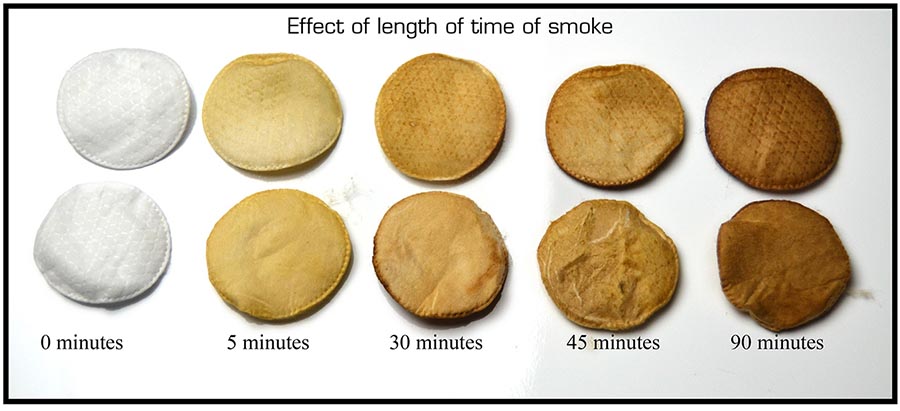

In one experiment, cotton discs were exposed to smoke for varying amounts of time. (See fig. 1.). This test was expected to be fairly linear — diminishing returns the longer the smoke. It was expected that as the discs became darker, there would be less surface on which new smoke could stick and the effect would reduce with time. The contrary is true.

As time increases, the smoking process seems to gain momentum. The difference in smoke build up between 45 and 90 minute is much more dramatic than the difference between five minutes and 45 minutes. It seems the build up creates a tacky surface for more smoke to bond with.

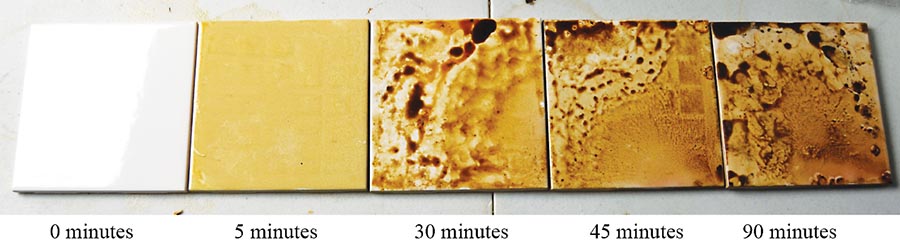

With white tiles, the effect is similar. (See fig. 2.) From zero to five minutes, the smoke creates a fairly even surface, but beyond that, the tiles appear spattered with smoke. After the initial layer forms, they seem to grab an enormous amount of smoke. The photographs may not reveal much difference between 45 and 90 minutes, but when touched, the 90 is far thicker, almost oily. The aroma of the 90-minute sample is the smokiest by far.

Temperature

Smoking temperature has a big effect on how well the smoke sticks. Two cans of soda were smoked. (See figure 3.)The can on the left was frozen solid, the other was smoked at room temperature. Clearly the frozen can absorbed a lot more smoke. However, the room-temperature can retained a cleaner, less-ashy character in the aroma.

Influence of the fuel source

The experiment below demonstrates some of the dramatic effects different fuel sources have on the smoked material. White cotton discs (for applying or removing makeup) were all smoked in the same position for 45 minutes in the same model of smoker, the Emson Electric Indoor 7 Qt Pressure Smoker. Several different types of fuel were used: pecan wood, angelica root, clove as well as fresh peppermint and spearmint. The samples of fuel sources were the same by volume but varied by weight, because of different densities. After smoking, the discs had varying levels of darkness and they also differed in weight.

Compared to other fuel sources, peppermint was by far the lightest, appearing just slightly different than before it went into the smoker. It is interesting to note, despite their similarities, spearmint and peppermint, gave very different results. Although lighter in color, the peppermint disc carried a more pronounced smell than the spearmint.

By far the smokiest disc to nose was the pecan wood. It was the densest and heaviest fuel source in the experiment which translated to a more intense smokiness. Angelica root was the next heaviest by weight and by smoky aroma. The most intense (non-smoke) aroma came from the cloves. Though the clove aroma pre-smoking was minimal, post-smoking it was greatly intensified.

Humidity

Water and humidity play an important role in the smoking process. A disk that was soaked was by far the darkest and without question had the strongest aroma. It had an ashy cigar smell. A disc was moistened with a spray mist but not actually dipped into water. It had the next strongest aroma. The dry disc retained the least amount of smoke, had the weakest aroma and carried a cleaner, “distant campfire” smell.

Fuel Format

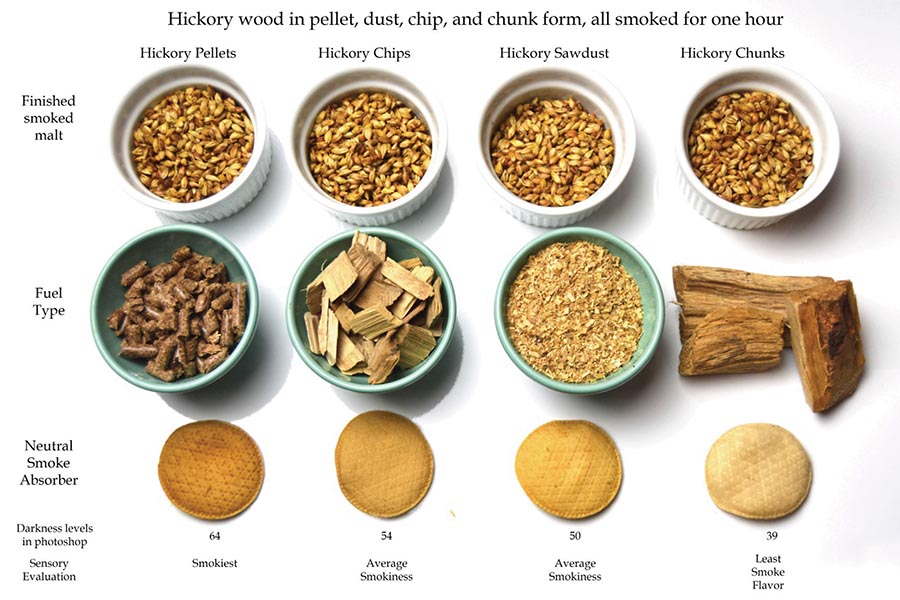

Wood comes in a few forms. When smoking meat on your grill, you might use wood chips. Smoking wood often comes as pellets, sawdust, or in chunks or logs. Pellets used to be controversial in the world of competitive barbecue, due to unnatural binders. Since, these have been eliminated. The cleanest tastes seem to come from using the pellets — another surprise.

The form of wood you burn has as large an influence on the final whiskey as does the way in which it is smoked. (See fig. 4. Smudges on the left are from handling the discs.)

Find your voice

Finally, I hope smoked whiskeys help aspiring distillers to find their own voice and further create distinction for the craft distilling movement. “Imitation is suicide” is one of our sayings around Corsair. When you imitate someone else, you are destroying part of your own personality. Smoked whiskey is a wide-open category with a lot of room for creative experimentation. Creating new smoked whiskeys lets distillers utilize what is local to them and make it their own.

If you live in the Pacific Northwest? Play with woods like Alder. If you live in New England? Try maple wood – it has a fantastic finish.

The point is this: find your voice. Make something new and original that the world has never tasted.

Happy Distilling!