Introduction

Over the past several decades, waves of change have swept through U.S. consumer behavior and attitudes towards food and drink. The trend towards fresh, “handmade” products made with real, and less-processed, ingredients has affected all segments, as consumers increasingly want assurances that their food and drink are safe, healthy and made with integrity. Knowledgeable and adventurous consumers also began seeking unusual and strongly-flavored products, instead of those designed for the mass market. Those tastemakers broadened the appeal of once unique and hard-to-find items.

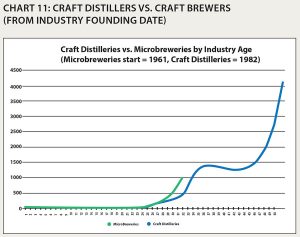

These waves affect drinking habits and norms. First came the “wine revolution” that began in the 1960s and continues to this day. Once, more than 95% of U.S. wine consumption was “jug wine.” Today, the amount is closer to 70%. And the number of winemakers has climbed from the mid-hundreds to more than 7,000 (more than 9,000 including virtual producers). Craft beer took up the baton next and has transformed the U.S. beer landscape since the mid-1980s. Once hard-to-find specialty items, one in every six beers enjoyed in the United States today is from one of more than 4,000 craft brewers.

Right on cue, 20 years later, America is in the thick of the craft spirits renaissance. Given the additional technical and regulatory challenges in distilling, it is not surprising that spirits came last. The craft beer renaissance began in earnest with the 1978 legalization of home beer making, but it is still a federal offense to distill spirit alcohol in any quantity without a TTB permit. Over the past several years there has been a measurable shift in U.S. adult beverage drinking habits from beer towards spirits. While overall per capita (over 21) alcohol consumption is essentially flat, spirits have been gaining “adult beverage share” (Distilled Spirits Council). And the craft-distilling boom is right at the heart of it.

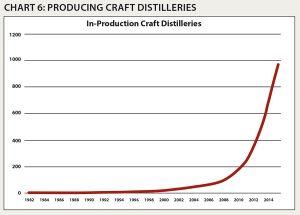

In “The U.S. Craft Distilling Market: 2011 and Beyond,” published in April 2012, 234 in-production craft distilleries were identified as of year-end 2011. I predicted, based on exponential growth that showed no signs of slowing, that the number of craft distilleries would be more than 1,000 within 10 years. To put it simply, the number of entrants started doubling every three years in the early aughts. With more than 250 entrants in 2012, it would take two more “three-year-doublings” to cross 1,000 six years later in 2018. So a 10-year prediction was quite conservative and left room for a slowdown.

In fact, the rate of new entrants has accelerated since then…

There are now more than 1,000 operating craft distilleries in the United States!

New Research: Analysis of DSP Listings

ADI seeks to provide the most thorough review of the craft distilling landscape available and have always expanded our efforts. Beginning in 2013, in addition to the ADI Directory listings, state guilds and Distilled Spirits Council affiliate members were taken into account to find new craft distilleries. This year, insights from the Alcohol and Tobacco Trade and Tax Bureau’s (TTB) Distilled Spirit Plant (DSP) listings have been added.

All “manufacturers” of beverage spirit alcohol (distillers, infusers, and bottlers/blenders) require a DSP, and the TTB publishes the list of current permit holders here: www.ttb.gov/foia/xls/frl-spirits-producers-and-bottlers.htm. What the TTB does not provide are past versions of the file or lists of new permits. Fortunately, I have been saving occasional snapshots of the file and now have enough history to analyze trends in new DSP listings and compare identified craft distillers from existing ADI Directory listings with the DSP files.

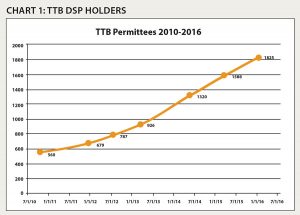

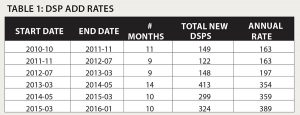

The saved files were collected at somewhat irregular intervals, but it is evident that the number of new DSPs issued goes from about 160 in 2011 to almost 400 in 2015. Table 1 shows the dramatic increase in new DSP rate, starting in 2013 and continuing to today.

A full analysis was undertaken of all new listings from the files dated November 2011; July 2012; and March 2013; and of a representative sample of new listings from the remaining three files. [ Table 1 ].

Nearly all (more than 95%) of the operating craft distilleries from the November 2011 and July 2012 files are listed and identified in the ADI Directory by 2015, demonstrating a lag time between market entry and identification for some entrants. And those who have not yet been listed are very few.

As Chart 2 shows, there appears to be a well-established “seasoning” process for new DSPs to become identified in the ADI Directory or guild listings. Recent years have followed right along with the pattern for prior years.

There is also an observable lag time between the issuance of a new license and the distillery ultimately releasing a product. Some registered DSPs never make it into production and vanish. Others, including many wineries and breweries, may add a DSP and maintain the permit for years without actually manufacturing spirits.

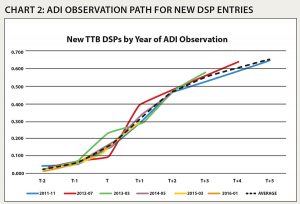

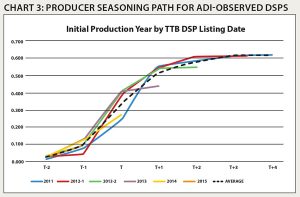

Chart 3 shows initial production date relative to DSP issuance date for those observed entries with ADI Directory or state guild listings. Here there is a measurable drop-off in the percentage of observed producers, particularly in those added in May 2014 and March 2015.

The reason is that a much larger percentage of the recent ADI listings represents actual producing distilleries—those that have a product on the market—rather than those just starting up or the “hopers and dreamers,” who may never get closer to market than their “under construction” listing in the Directory.

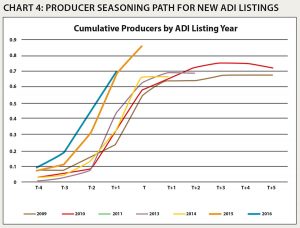

Chart 4 shows 70% of new ADI listings over the past two years are already producing in the year prior to listing. That is, 70% of the new listings in the 2016 Directory have already started producing by year-end 2015—more than double the average of prior Directories. This could be the result of greater outreach on the part of ADI to identify true entrants and include them in the Directory, or it could indicate a change in the “path to market” for newcomers as the craft spirits boom enters its next phase.

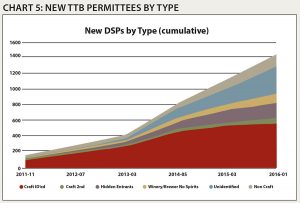

Chart 5 segments all new DSP holders by type:

“Craft ID’ed” are those observed in an ADI Directory or guild listing;

“Craft 2nd” are new DSPs from existing craft distilleries (change of location, etc.);

“Hidden Entrants” are craft distillers known or estimated to be producing;

“Winery/Brewery-No Spirits” are operating wineries and brewers with a DSP;

“NonCraft” are packagers, majors, and the like; and

“Unidentified” are those who have no footprint beyond their DSP listing.

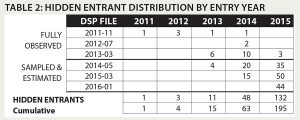

By taking a sample of DSP holders that were unobserved in May 2014, March 2015 and January 2016 to arrive at estimated frequencies of these types, the full set was extrapolated, and reasonable assumptions were made regarding entry dates of the hidden entrants based on known trends. Table 2 details the distribution, by DSP date and entry date, of those hidden entrants. Note that the estimate of 195 current hidden entrants does not include the 342 remaining “unidentified” DSPs, many of which will become producers in the coming years. [ Table 2 ].

Market Growth & Trends

With these estimates of hidden entrants, we arrive at a more robust view of the landscape of U.S. craft distillers, as shown in Chart 6. Note that although recent growth looks outrageous numerically, the growth rate follows a normal exponential path. [ Chart 6 ].

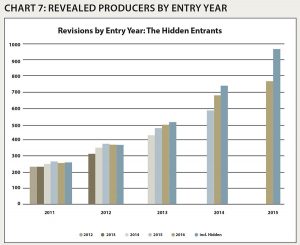

Searching more deeply for hidden entrants reveals that revisions of prior years uncovered significant numbers of existing, but unseen, producers. As Chart 7 shows, our count of 2011 entrants rose from 234 in 2012 to 262 in 2015. More recent years have naturally been subject to larger revisions, as newer entrants may not yet be in the ADI Directory or a state guild in their early days. Thus, our count of 2013 entrants rises from 425, in the 2014 paper, to 492 entries now (and to 507 including previously hidden entrants), while the 2014 entry cohort goes from 588 observed last year to 675 this year (and 738 including an estimated 68 hidden).

Time tends to reveal those in production. With four or five years of seasoning, most entrants in a given annual entry cohort are visible. Thus, in some sense, including these hidden entrants is simply front-loading the discovery process. Many of those now hidden will be revealed in coming years. Many of those labeled unidentified will ultimately enter the market, even if they are still in the formative phases. [ Chart 7 ].

However, there is another side to this tremendous growth story. Not all who put plans in motion to open a craft distillery end up doing so. There are the “hopers and dreamers” with an “under construction” listing in an ADI Directory, and maybe even a license, but who never get any further in the process. We call these “pre-producers.”

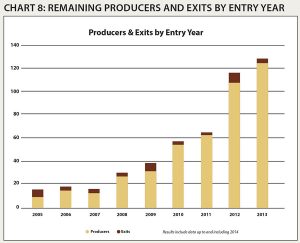

And there are those who actually make it into production, release a spirit for sale, and then exit the market, either through an acquisition, a wind-down, or direct bankruptcy. Those are called “exits,” and enough have now been observed to share some data. The first observation is that it is very rare for a producer to start and exit in the same year, or even only a year later (although this may change). That is, there is usually a lag between entry and ultimate exit.

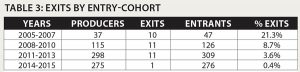

Chart 8 shows the numbers of exits and remaining producers by entry year. Just as the unidentified DSPs are potential entrants, all current producers are potential exits. Table 3 demonstrates that exit rates generally increase with time. The next several years should reveal hundreds of exits as the craft distilling market matures.

A natural question is whether there are any characteristics of the exits that might be instructive for those now producing or considering entry. One element that seems to be highly correlated to exit likelihood is the number of product categories. “Monoline” producers–—those releasing only one class of spirit—are much more likely to exit than those producing in more than one category, and there appears to be a linear effect (more data will help confirm these findings).

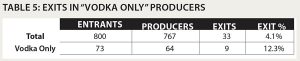

[ Table 4 ] This effect could also be masking a “hidden factor,” that of actual distillation versus sourcing and bottling. Most self-described craft distilleries are actually distilling. Some are also sourcing externally (to bring a product to market now) while distilling other products for later release. And some are not distilling at all, but are exclusively sourcing external spirit to blend and bottle. It can be difficult to tell these “manufacturers” from actual distillers, but the practice is most prevalent in the vodka market, where GNS plus water plus a nice label becomes a “Hand-Crafted, 6x-Distilled Premium Vodka.”

[ Table 5 ] Looking strictly at those monoline producers making vodka there is a significantly higher likelihood of exit. With a large number of existing brands, challenges to differentiate on taste profiles, and low existing pricing expectations, a true craft distiller making only vodka faces squeezed margins, while those simply watering down GNS have no barrier-to-exit in the form of capital equipment.

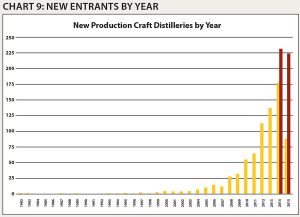

The increase in exits will inevitably start to put the brakes on the number of net new entrants each year. But the number of new entrants continues to climb. In fact, the entry rate itself seems to be doubling every two years from about 30 in 2008–2009 to about 60 in 2010–2011 to 110 in 2012–2013 to 220 in 2014–2015. Chart 9 shows the progress of new entrants, with 2014 and 2015 including both the identified (gold) and total, including estimated hidden entrants (red). The “decline” from 2014–2015 is likely due to our conservative estimate of the hidden entrants for 2015. Recent years are still likely to be revised upward, although hopefully by less.

Craft Distilleries by Product Type

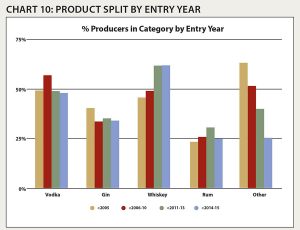

Chart 10 illustrates that the trend toward whiskey continues, and it is likely that recent whiskey-focused producers could remain hidden while aging their initial releases. As noted in previous editions of this paper, the drop in “other” reflects the composition of early entrants, which was more heavily weighted towards wineries and orchards producing brandies. Vodka, gin and rum have all held reasonably steady in their respective popularity. Because distilleries can be producing in multiple categories, these numbers sum to more than 100%.

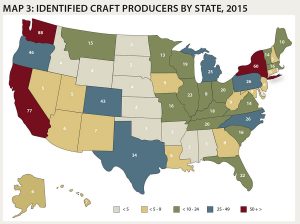

Craft Distilleries by State

We can now safely say that there is a producing craft distillery in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

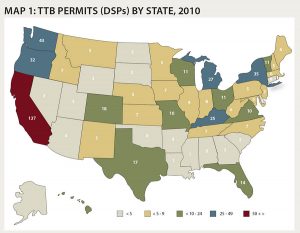

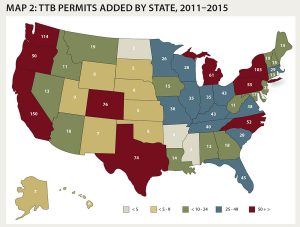

Maps 1 and 2 below detail, respectively, the number of total DSPs outstanding as of year-end 2010, and the number added since then by state. Growth is nationwide and extraordinary over the period, particularly in the Appalachians and Deep South with their long history of small-scale distilling and recently-loosened state licensing laws. The Carolinas go from 10 DSPs to 80, and Georgia-Alabama-Mississippi-Louisiana from 5 to 46. Meanwhile, the top states like California, New York, Washington, Colorado, and Texas each added from about 75 (CO, TX) up to 150 (CA).

Map 1: TTB Permits (DSPs) by State, 2010

[ Map 2 & 3 ] Looking only at identified producers shows broad agreement with the growth in DSPs.

Comparison with Craft Brewing Market

As noted above, in addition to the extraordinary number of new entrants, distilleries have been exiting the market. Currently the number of entrants overwhelms the number of exits, but as the market matures, that won’t always be the case. The dip in the brewers curve represents the time from the late ’90s to the mid-’00s, when the number of exits exceeded entrants.

Since 2006, craft brewers have resumed the exponential growth that appeared finished. Their numbers have tripled in the 10 years since then, driven this time by microbreweries rather than brewpubs. The “distillery-bar” phenomenon is beginning to catch on in craft distilling, but Prohibition-era tied-house laws still need reform in many places to turn this into a viable trend.

Meanwhile, the craft distilling market appears to be ahead of the craft brewers at the same point in their development. This is likely not an anomaly but the result of the more rapid spread of information in the Internet age.

Conclusion

The craft distilling market is no longer in its infancy. The pioneers of the ’90s and ’00s yielded to the explosion in new entrants over the past few years. And now we are seeing some of those entrants departing. The next phase of the market will see increasing numbers of exits, even as the number of new entrants continues to grow.

The dynamics of consumer demand and the prior examples of farm wineries and craft brewers suggest that the craft distilling market is far from saturation. However, the days of bottling GNS-based vodka and calling yourself “The First Distillery in Which-Where County Since Prohibition” may be over. Knowledgeable consumers are seeking truly local products with panache and differentiation.

The next milestone, 2,000 craft distillers, will not take nearly as long as the 33 years for the first 1,000. But it will take longer than three years for the next doubling to that level. ADI predicts another 1,000 net entrants over the next five years, and that number of craft distilleries will ultimately match the number of craft breweries. z

[ Note ] Sincere thanks to Glenn Carroll at the Graduate School of Business, Stanford University; Anand Swaminathan at the Goizueta Business School, Emory University; Bill Owens, Andrew Faulkner, Gail Sands and Christy Howery at the American Distilling Institute; and Bart Watson of the Brewers Association.

This brief is an update to the White Paper I released in April, 2012, “The U.S. Craft Distilling Market: 2011 and Beyond.” The original paper is available at: http://bit.ly/HxUwj1.