Sales need to grow, right? But first, whiskey needs to age. Those distillers that have been making whiskey for a while now have probably dealt with this firsthand. Those of you just entering this space may not have dealt with this yet, but you probably will. It’s inevitable. Anytime you make products several years before you can release them, you’re going to run into problems. At least with whiskey, you’ll probably have some options. So how do we organize and manage this dilemma?

Let’s set up this hypothetical scenario:

ABC Distillery was created to produce and sell primarily three types of whiskey: bourbon, rye and single malt.

They will only release their three core products after 3 years of aging in barrels.

They have been in business for a number of years now and have been releasing spirits.

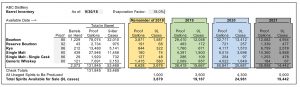

Chart A shows the summary from their current barrel records:

Observations related to this scenario:

Aside from its three core products, you can see the company has added a few more, including a special reserve bourbon and a single-cask single malt whiskey (both as a means of creating some interesting, high-margin releases), a “generic” whiskey (carrying a lower price point than their core products and making use of “second fills” on their emptied barrels) and some unaged spirits (such as white dog, vodka and/or gin used to create some current cash flow and satisfy all buyer categories for their on-site visitors). We’ll discuss some of these further below.

Company management knows “proof gallons in” to barrel do not equal “proof gallons out” when the barrels get emptied and, based on their historical experience, they’re using an 18% loss factor to the angel’s share. This helps them more accurately forecast what will actually be available for sales after three years in barrel.

For the remainder of 2018 (3 more months, in this scenario), you can see they only have about 2,679 cases of adequately aged whiskey left to release. Based on what they’ve allocated for 2019 and 2020, it would appear they don’t have as much fully aged whiskey as they would like to get them through what is normally the biggest quarter of the year.

For 2019, it appears that, in a best-case scenario where every drop of whiskey they have allocated for next year gets sold, they would release 38,419 proof gallons from their barrel inventory, equating to about 15,667 9-liter cases after factoring in the angel’s share. If they sell each 9-liter case at wholesale for $200 (putting their products in the $34–$37 price range on the shelf), their expected revenues next year would be a little over $3.1 million.

For 2020, they have stashed away 20,000–25,000 cases, allowing for double-digit growth. And they can always make more unaged spirits, if market demand allows it, to provide for even more growth.

As for 2021, they still have some work yet to do if they are going to forecast growth into that year. In fact, at their historical pace of producing 50,000 proof gallons of whiskey annually, they may not be able to produce enough whiskey to get that proof gallon number for 2021 up into the 60,000 proof-gallon range in the next couple of months. (Remember, they won’t release any whiskey until it’s aged at least 3 years, so they only have until about the end of November 2018 to affect their 2021 sales). They may have to back down their 2020 forecasted whiskey sales in order to slide some of this inventory into 2021 if they wish to create a nice continuous growth ramp.

Now let’s take a look at their current projected product mix over the next several years.

As you can see, bourbon appears to be their flagship spirit. But availability of it spikes significantly in 2019 and then flattens in 2020. This may be the result of management believing rye and single malt sales are going to increase more significantly in the future, or it may just be that they didn’t make enough bourbon back in 2017 to keep themselves properly supplied. Regardless, it looks like they will need to spend the balance of 2018 making almost entirely bourbon if they want to avoid empty bourbon shelves in 2021.

And, again, if they wish to keep their growth in the 20%+ range, they only have about two more months to get 11,000–13,000 more cases (28,000–31,000 proof gallons) put away for 2021. Assuming they have the production capacity to do this, it will surely put a strain on cash as they invest heavily in grain and labor hours to make this happen.

Now, more thoughts on how best to manage the perils of producing whiskey 3–5 years ahead of the related sales cycle:

First of all, you’ll need access to a lot of cash. In the above scenario, the distillery had 131,845 proof gallons put away and was going to need to rush to make another 30,000 proof gallons yet this year in order to keep its sales ramp intact for 2021. At $8/PG, that’s about $1.3 million tied up in inventory, excluding barrel costs (2,500 barrels at $200 = another $500,000) and warehousing space. And with a small craft distillery, it may cost more than $8 to make a proof gallon. If this company is turning a nice profit, it may be able to finance this inventory expansion by borrowing the needed funds from a bank. If not, most of this cash may come in the form of equity from investors. In either case, it can take months to obtain this financing.

Just from this simple example, you can see this company has done a number of things to assist with cash flow and “evening out the bumps” in its sales forecast. For one, they’ve introduced some unaged spirits to allow for immediate cash flow — they can produce it one week and sell it the next. Secondly, they’ve added a couple of high-margin products (an older reserve bourbon and a single-cask single malt) to pique the interest of their customer base and make incremental sales. Thirdly, they’ve added a generic or value whiskey to their portfolio, as a means of both (a) getting a second use out of their barrels and (b) blending some of their otherwise unsold barrels into a new, lower-priced offering to convert these barrels to cash.

Aside from what is apparent in this example, there are other ways of managing shortages or excess inventory as production and sales plans change over time. With shortages (such as the small amount of remaining bourbon the distillery has for 2018 in Chart A above), you could:

Raise the price of the product (or at least end any incentives and promotions).

Increase emphasis on other products (through incentives and advertising/promotion).

Tap some of your more valuable reserve barrels (simply as a means of keeping your shelf presence intact for your flagship spirits).

Reduce the package size and emphasize this new, smaller product.

Buy some whiskey to supplement your own (if you can meet the legal and packaging requirements and aren’t concerned with distilling your own product).

Allocate this product by requiring purchase of other of your products along with it (if demand for this spirit is strong enough to pull this off).

Managing excess inventory is probably easier to deal with, as long as you don’t find yourself in a cash crunch as your money stays tied up in this extra inventory. With excess inventory, you could:

Provide discounts or increase sales incentives to get the spirit moving.

Create a new “reserve” or 5-year-old category as a premium-priced release in a couple of years.

Sell off some of the 3-year-old barrels via transfer in bond on the open market to other distilleries for cash.

Transfer a portion of the related barrels into the “generic” or value whiskey category.

Simply stop making so much of that product and devote more production time to other spirits, allowing this problem to correct itself over time.

Where scarcity of cash is not a problem, it seems easier to deal with excess inventory than a shortage of inventory. After all, making whiskey is probably easier than selling whiskey, at least on a larger scale. And whiskey seems to get better with age, likely increasing in value at a faster rate than it evaporates. So the last thing you want to do is lose momentum on the sales side by running short on spirit, as the value of a company can be largely impacted by its sales ramp.

That said, if you’re not prepared to spend $50–$100/case (or more!) selling your first cases in a given new market, then don’t make the whiskey with the intent to later sell it by the case. You can spend all your money making whiskey, but if you don’t have the money to sell it, it will slowly evaporate like the cash you once had.

Another observation to point out regarding the relationship between the production and sales of whiskey or, for that matter, any barrel-aged spirit, is that there can be an “accordion effect.” When sales outpace production, the whiskey gets younger, causing lower consumer interest in the spirit. This, then, causes sales to slow. As sales decelerate, production begins to, once again, outpace sales, causing the whiskey to get older, where sales begin to climb again. If your cash holds out during these cycles, they have a way of correcting themselves, as long as you are in touch with what is happening and manage what you can.

Reviewing this simple example above helps us understand a lot about what has happened in our larger industry over the course of many decades. A company may start out making only one kind of premium whiskey and later find itself releasing a cheaper version of the same product (i.e., indicating overly aggressive sales plans that couldn’t be met, over-performing production output or a lower quality spirit than was intended), or it may find itself buying aged whiskey from others or raising its prices (indicating more demand for the product than was originally projected a few years prior).

In any event, you can see the value in projecting and regularly monitoring each of your aged spirits into future years, barrel by barrel. By setting up a process as simple as the one shown above and monitoring it monthly, you will have more time to react to the changes that are inevitable in your business and make the best possible choices after weighing your many alternatives.

Click for a larger image.

Click for a larger image.