While recipe preparation is an art, designing a recipe has a method that borders on the scientific

Every successful gin, aquavit, and absinthe must possess a variety of qualities but one that is essential is a unique botanical recipe; one that attracts the drinker and draws them back, sip after sip.

The recipe is not just what botanicals are used, nor their ratios; it involves multiple variables, each of which can make a massive difference to the end product. These variables include, but are not limited to:

- What botanicals are used and where they’re sourced from?

- What ratios of botanical ingredients are used?

- How are they processed?

- How long are they macerated for (if at all)?

- What strength of spirit is used for the charge or maceration?

- What is the character of base spirit?

- What botanical cuts are used?

- What still is used and how do you use it?

- What are the environmental conditionals of the distillery?

The purpose of this article is to introduce the readers to some of the decisions that they will have to make (although each point could easily be an article in its own right!).

Botanical Selection

It is helpful to think of gin or botanical spirits as being a balance of three elements: water, alcohol, and botanical oils (see Figure 1). All of the permutations discussed above are just different ways of adjusting these.

figure 1

figure 1

If you are making gin, then your selection must include juniper (with aquavit, it’s caraway or dill seed). Depending upon your jurisdiction (such as the EU), this “Juniper” must specifically include juniperus communis (common juniper), but other locations, such as the USA, have a more relaxed approach.

Next up is coriander seed. Some distillers are put off from using this by a dislike of the soapiness of coriander leaf (cilantro) but coriander seed has a more peppery or citrus qualities especially those spruced from Russia or India.

For a classic or London Dry Gin, these two ingredients will make up the majority of the botanical mass of the gin recipe, perhaps up to 70-80%. It is common for many classic gins to have quite similar quantities of juniper and coriander.

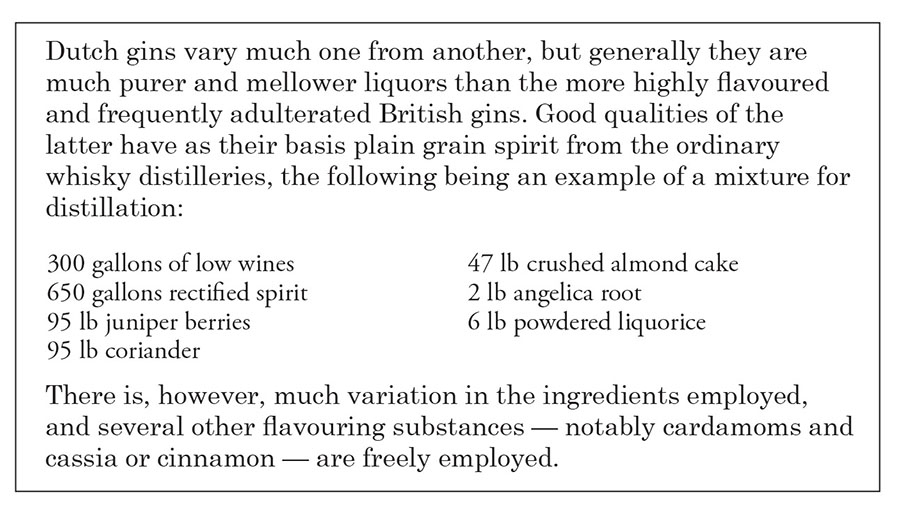

The recipe in Figure 2 first appeared in the 9th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica from 1875. It uses a combination of low wines and rectified (aka neutral) spirit and equal quantities of juniper berries and coriander seed. The “crushed almond cake” is not a confectionary pastry, but rather a way in which almonds were transported, similar to a “cake of soap.” It is interesting that no citrus is mentioned, even though Beefeater (which is made using both lemon and orange) began production fifteen years earlier in 1860. Either way, it seems that citrus was a lot less popular then than it is today.

figure 2

figure 2

Readers could be forgiven for concluding that perhaps what is often thought of as the flavor of “gin” has just as much to do with coriander as it does juniper, and perhaps they would be right.

Other common botanicals include angelica root, which has an earthy flavor and gives gin a distinctive dryness, and liquorice root, which adds sweetness and a smooth mouthfeel.

Beyond this, botanicals mostly fall into five broad categories: citrus, herbal, spice, fruit, and floral. Some of these really “punch above their weight”, botanically speaking, and should be used sparingly. Examples include citrus peel, anise, and cardamom.

This final selection of botanicals typically makes up between 10% and 30% of the mass of the botanical recipe. For example, the following for about 100 litres of charge at 50.0% ABV*:

- 1000g juniper

- 800g coriander

- 200g angelica

- 60g lemon peel

- 60g lime peel

- 15g green cardamom

- 10g orris root

*N.B. This higher charge is not suitable for some stills; always check your still’s manufacturer’s instructions. Recipe for illustration purposes only.

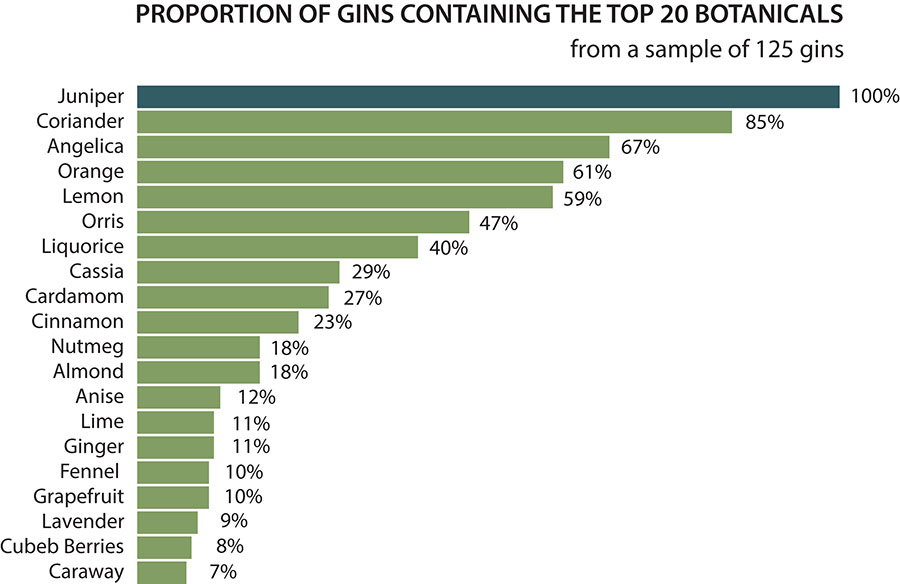

Figure 3 shows the results of a survey of the botanicals used in modern gins; the graph shows the most commonly used botanicals from a sample of over 120 gins.

A word on the quantity/mass of botanicals in a still: whilst an exact figure depends on individual circumstances, a survey of distillers found that most fit in the range of 8-25g of botanicals (in total) per litre of 50.0% alcohol. This figure relates to single-shot distillation; multi-shot/concentrate methods will be discussed in the next article.

figure 3

Sourcing & Processing Botanicals

The sourcing and processing of botanicals are just as important as the ratios that they’re used in. Botanicals from different locations will have different flavor profiles, as previously mentioned with coriander. It is important to find a reliable source for your botanicals that can accommodate your orders as demand increases.

When it comes to processing, there are advocates for the use of both fresh and dry botanicals. Some praise the intensity and consistency of dried botanicals, whilst others feel that using fresh botanicals gives them more choice and a brighter flavor. Which to use is a decision that a distiller needs to make for themselves, ideally after experimentation.

A good way to gain some insight into what flavor profiles are produced by a range of botanicals is to distill them individually. Although this can provide a lot of information independent distilling consultant, Julia Nourney has a word of caution:

“One of the biggest mistakes that I see is people creating their recipe on a small still and then simply multiplying it up to make it on a larger still; it just won’t taste the same.”

This is because the scaling up process is non-linear, and botanicals that are very oily and “punch above their weight” are particularly problematic. Instead, once a distiller has a general idea of their gin recipe, it is best to finalise it on the production still.

Another common process for botanicals is crushing, grinding, or milling them before maceration and/or distillation. These processes increase the surface area of the botanicals and, thus, the rate of oil extraction. This is quite commonly performed on cardamom or juniper, although some experts caution against it, citing the risk of a stewed flavor profile.

Maceration — the soaking of the botanicals in alcohol prior to distillation — can help to extract more botanical oils and can be used for all either a proportion or all of the botanicals in your recipe. In this step, the variables available to the distiller are:

- duration (time)

- whether the botanicals are crushed or not,

- the strength (% ABV) of the maceration alcohol.

Occasionally, distillers will also heat their maceration vessel (which may just be their pot still) to aid with the extraction process known as digestion.

The choice of ABV for your maceration spirit will depend largely on your choice of botanicals and what kinds of flavors you want to extract. If a distiller is just using juniper and coriander, then their flavor compounds are soluble in alcohol, but not water, so a maceration spirit of 50-60% ABV might be used. For more delicate flavors where the compounds are soluble in water, such as those from flowers or lemongrass, a lower ABV spirit can be used, e.g. 30-45% ABV.

Some distillers macerate flowers in water alone, making a floral botanical “tea” that can then be added to the alcohol in the still to reduce the ABV of the charge prior to distillation.

Even if distillers are not macerating prior to distillation, careful consideration needs to be given to the alcoholic strength of the charge. It is generally considered safest to reduce the ABV of the charge by adding the required amount of water to the still before adding the spirit. This is because the air displaced from the still when alcohol is added can sometimes carry some of the alcohol as fumes.

Once again, the ABV of the charge will depend upon the water/alcohol solubility of the flavor compounds that you want to extract. Typical charges range from 40-60% ABV.

Taking Botanical Cuts

When distilling, it is important to consider botanical cuts. This has nothing to do with methanol, as in the distillation of whisky, brandy, rum etc. Instead it is about finessing the desired character of your gin. Different flavor and aroma compounds come over the still at different points in the run. The first liquid that comes over has the highest ABV and is known as the “heads”, the tasty middle bit (the bit that you want to keep) is the “hearts”, and the last portion that comes across the still is the “tails”.

A good way to understand cuts is to run a distillation and take samples throughout and nose them in a glass. On a smaller scale, you can also collect the spirit in fractions; so for a 1 litre run this might be every 50-100ml. Set out the samples in separate containers in the order that they came off of the still. Start sampling from the middle; if you like the character, add it to a larger container that will become your gin. Work your way through the other samples, from the middle out. When you get to the outer samples, don’t add any with undesirable notes to your larger container.

Depending upon the botanicals used in the recipe, the samples collected earlier in the distillation will contain the more volatile flavor and aroma compounds, as they distill first. This can express itself as an intense citrus flavor, but can also quickly change to a slightly acrid, fishy, salty note, which is far less appealing.

After the hearts, the heavier compounds come over the still and the ABV of the distillate will drop, too. Green, leafy, piney notes tend to be included in this section, but also as the run continues there are more stewed, dirty, funky, vegetal flavors that are considerably less pleasant.

When you are satisfied with the character of your distillate, water needs to be added to proof the spirit to bottling strength. In some cases, a distiller may find that their gin heats up slightly during proofing, so may need to be left for an hour or two before being tasted or appraised further.

Next Steps

The information and steps noted above will take you one step closer to finalising a botanical recipe, but there are additional factors to consider. In the next article on botanical recipes:

- Equipment, including the impact of using vacuum and vapour baskets

- Fixatives

- Making the most out of your still: the multi-shot method

- Environmental conditions and their impact upon distillation

- Basic troubleshooting