Thinking big is never a problem for the Sazerac Company — billion-dollar mega-importers with more than 2,000 employees, nine distilleries and 300-plus brands around the world.

Thinking small, however, is a new experience for the Louisiana company based in Metairie.

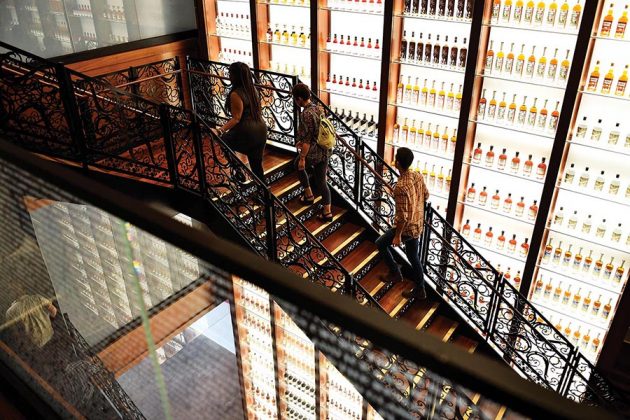

With the October 2019 opening of The Sazerac House, a free-admission, spirited cocktail museum at the corner of Canal and Magazine Streets in New Orleans, that is exactly the challenge for distillery supervisor David Bock. The impressively restored historic 48,000 sq. ft. building welcomes visitors with a series of interactive exhibits and hands-on classes led by drinks historian Elizabeth Pearce, whose Drink & Learn tours raise a high bar for cocktail aficionados. The space is gorgeous, anchored by a three-story back-lit wall showcasing 1,010 bottles and a dramatically curving staircase. Floor two digs deep into the company’s portfolio, with spaces for tastings and detailed information on production. The third floor is reserved for New Orleans drinks history, dating back to the turn of the 20th century.

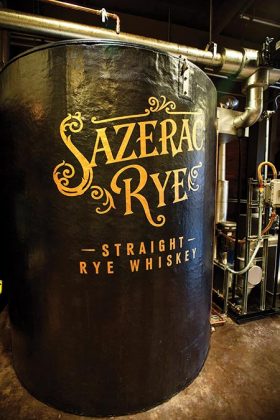

But at the heart of Sazerac House is small-batch production overseen by Bock. Both Sazerac Rye and Peychaud’s Bitters are produced on-site, a small-volume enterprise designed to showcase the process and the brands’ ties to New Orleans. The facility’s four 1,000-gallon cookers and 500-gallon still can produce about a barrel a day (365 barrels a year). Compare that to the 51,000 barrels of Sazerac Rye produced annually at the company’s Buffalo Trace operation in Kentucky. “The little distillery that could” is open for business.

“Our goal is to showcase an authentic production process to guests at The Sazerac House,” said Bock, who came to the job from NOLA Distilling, where he was both head distiller and one of three founding members of the Uptown craft distillery. In his role overseeing the first distillery in the Central Business District, Bock brings his track record for small batch distilling to the table.

The company’s long history in New Orleans gives it credible heft, noted Pearce, whose latest book is Drink Dat New Orleans. “While the Sazerac Company has grown into a big importer making beautiful bourbons in Kentucky, its origin was about as small batch as it gets.”

Peychaud’s was one of the company’s earliest brands, dating back to 1873 when Thomas Handy acquired the rights to the iconic bitters. Handy went on to bottle and market the Sazerac cocktail in the 1890s, along with Herbsaint in the 1930s, evolving the business into what is now the Sazerac Company.

“The Sazerac House does a really good job of taking the visitor by the hand and tracking the history of spirits in New Orleans,” said Pearce. “It’s worth remembering that even a brand like Sazerac Cognac comes from one small house in France. Many brands were named for the people who produced them, which shows the human small-scale elements of many of our favorite spirits.”

The Sazerac House isn’t the company’s first foray into connecting the dots between a brand and a spirit’s regional history. At its Buffalo Trace Distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, bourbon drinkers can take a history tour focused on Prohibition-era production in buildings that have earned National Historic Landmark status.

What he’s really trying to do in New Orleans, said Bock, is show and tell — show the guests the fermentation and distilling process, and with Pearce’s help, tell the spirited stories that created a foundation for an American success story. All that inspiration leads to one place, of course: the building’s gift shop, where visitors can buy spirits crafted on-site and around the world, liquid souvenirs that just might not make it home.