At Montanya Distillers in Crested Butte, CO, Karen Hoskin has assigned names to her trio of rum-producing copper pot stills: Bella, Bellisima and Bellatrix. Each has its own personality, she insists. Bellatrix, for example, has a “spike-heeled attitude” and “puts out more rum than the others, so she’s earned her stripes as the most badass of the three.” Meanwhile, she envisions conversations between Bella and Bellisima: “We joke about how they’re in an ongoing fight, arguing over which one is the most beautiful.”

Some people name their cars or their boats. So perhaps it only makes sense that some distillers, who spend as much time with their beloved hooch-making apparatuses as their loved ones, also name their stills.

“We name pretty much everything we use on a regular basis,” Hoskin notes, from Helga, the workhorse bottle filler, to Prince, the oft-finicky label machine. So why not the stills too?

“It’s just easier and more fun to refer to the equipment as anthropomorphized than just ‘the still on the left’ or ‘still #3.’ That sounds so lifeless,” Hoskin explains. “And these pieces of equipment are so filled with life and have so much personality.”

She’s far from alone in this sentiment.

The vast majority of named stills are named in homage to people, whether real or imagined. For example, at A. Smith Bowman in Fredericksburg, VA, master distiller Brian Prewitt introduces the 30-foot-high still there as “my good friend Mary,” named after Mary Hite Bowman, who was the mother of the Bowman brothers who founded the distillery. A much smaller (eight-foot-high) still was added later, expressly for making gin. It was named for Mary’s husband, George.

Meanwhile, at Privateer in Ipswich, VA, the primary still (used mostly for rum, but also for annual single malt whiskey and gin runs) is named James Baldwin after the legendary writer, poet and civil/gay rights activist.

“I knew right away I was going to buck tradition and not inherently name it after a woman,” recalls Privateer president Maggie Campbell. Lead Distiller Peter Newsom suggested the name Baldwin, “one of our favorite thinkers and artists.”

Baldwin serves as a daily reminder of inspiration, Campbell said. Merely invoking the name “commands our respect, focus and best work.”

At Durham Distillery, president/CEO/co-founder Melissa Green Katrincic dubbed a 230-liter Mueller still as Gertrude, the name of her maternal grandmother, who lived until she was almost 92. “She was a force in her own right,” Katrincic recalls.

“Whenever I was about to get in trouble or was a bit of a hothead with my grandmother when I was little, she would tell me, ‘Don’t have a conniption!’” Today, Durham’s flagship bottling is Conniption Gin, and it’s in Gertrude’s honor, Katrincic said, that the back label of each gin bottle now reads, “Go Ahead. Have a Conniption.”

Meanwhile, at Chicago’s Rhine Hall Distillery, Stanley is the still that makes brandy and fruit eau de vie. The name Stanley has a dual meaning, explains owner Jennifer Solberg Katzman. “Primarily, Stanley is the name of my business partner’s best friend, the originator behind helping make the product we make today,” a man also referred to on all the labels as “Stan the Man.” But the second meaning is for the Stanley Cup, the top award given in NHL hockey; that’s a nod to Solberg’s father, Charlie Solberg, who was a professional hockey player in Austria, where he was first introduced to eau de vie. (Rhine Hall is named for the ice rink where he played.)

Sometimes, stills arrive with names and history already attached. At Royal Foundry Craft Spirits in Minneapolis, MN, Miss Dana, a stripping still purchased from a prior distillery in Virginia, had already been named for the first owner’s wife. “We told the owner we’d keep the name,” said co-founder Nikki McLain.

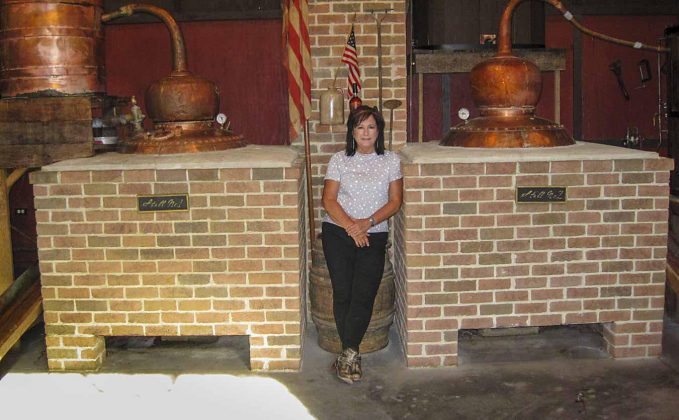

In other cases, the name is a reference to the still’s functionality. That’s the case at Lassiter Distilling in Raleigh, NC, where executive director Rebecca Denison chose the deliberately cheesy name Distill My Heart for a custom-built pot-column hybrid rum still as “a reminder for us to put a little love, a little of ourselves in every bottle.” It also has double meaning, referring to the heads/hearts/tails of a spirit run: “We take our cuts really seriously and conservatively.”

Similarly, at Indian Creek Distillery in New Carlisle, OH, a pair of whiskey-making stills are fondly referred to as “the girls.” Explains owner Missy Duer, “The Singler is the ‘working girl’ ’cause she distills twice as much as The Doubler, who can be a diva now and then.”

Sometimes the name is a reference to the physical characteristics of the still itself. The polar opposite to Montanya’s trio of Bellas, all dubbed “beautiful” in reference to their particularly curvaceous contours, is Ugly Betty at Scotland’s Bruichladdich, the name given to the lone still that makes gin, not Scotch. Designed in 1955, it’s described as a cross between a pot still and a column still; key to the design is a thick column-like neck with three extra removable sections for flexibility—not the most graceful appearance.

Meanwhile, the smallest still at Scotland’s Mortlach distillery is named Wee Witchie. In the 1960s, then-distillery manager John Winton named it after its unique shape: fat and rounded at the bottom and pointy at the top, resembling a pointy witch’s hat.

And sometimes it’s a way to make the very technical act of distillation seem more accessible or relatable to a broader audience. At North Shore Distillery, just north of Chicago, master distiller Derek Kassebaum nicknamed his German-made copper pot still Ethel. (As in “ethyl alcohol,” get it?) People really seem to connect with Ethel: She’s probably the only still to have a Twitter account (@StillEthel, with over 700 followers); guests write her letters, and she’s even received a phone call or two.

While some distillers opt to endow names based on little more than a fleeting whim, others do it out of genuine affection or respect for the still that contributes so much to the distiller’s daily endeavors. “We are really interacting with our equipment,” Hoskin sums up. “We really feel like there is magic in our stills and in our fermentation tanks. They’re alive.”

Of course, it’s possible that some feel this tradition imbues an inanimate object with a little too much personality. When Brian Lee, co-founder of Tuthilltown Spirits was asked during a distillery tour whether he named his still, he seemed taken aback. “Never!” he cried. “These stills need to be repaired and replaced pretty often. If I named one, I’d get too attached to get rid of it.”