A bartender serves up an ice-cold Martini. (If it helps you visualize the scene, let’s say it’s a 7:2 ratio, served up with a twist. Stirred, naturally.) The customer chose a bright, citrus-forward gin. She takes in the beautiful aroma. Some Meyer lemon, maybe some verbena and bergamot. As she chats with her friends over her drink, the Martini warms. Molecules from the gin scurry into the air and are gone.

What if there were some way to retain those delicate, light aromas so that the last sip had the same brightness as the first one?

Perfumers have long pondered how they could design products that retain their scents and aromas longer. The literature on perfume is rife with ingredients that are said to have the power to “fix” aromas in place longer. These ingredients are called fixatives.

You don’t have to look far to find distillers talking about fixatives. At some point in the last century, the idea that orris root and angelica are necessary ingredients because of their fixative powers has become gospel among gin distillers. The ADI forums are replete with questions (and answers) about fixatives in gin. As the craft spirits industry has matured, more and more distillers have sought inspiration and knowledge from related professions. It seems apt to pause and look at what fixatives are, how perfumers and chemists think about them and where the current understanding of these ingredients leaves distillers and the industry.

What are fixatives and why are we talking about them in spirits?

In Western European culture, both gin and perfume share a common lineage—the medieval monastery. In the 16th century, they moved to the apothecary where you could find a distilled juniper aqua vitae on the shelf next to a plague-preventing juniper scent. Far from city centers, distillation was part of a homemaker’s duties. Books published in the 16th century included recipes for perfumes and medicinal spirits side-by-side. The traditions of spirits and perfume are bound through history, therefore, it should come as no surprise that we see facets of one informing facets of the other.

When perfumers talk about a fixative or “fixing” a perfume, they are talking about two things. First, The New Perfume Handbook describes a fixative as an “ingredient which prolongs the retention of fragrance on skin,” and is also sometimes described as “tenacity.” The other definition is summed up by The Chemistry of Fragrances as “a property of some perfume components, usually the higher boiling ones, which enables them to fix or hold back the more volatile notes so that they do not evaporate so quickly.” A fixative keeps the scent around longer. In the world of spirit production and distillation, we’re talking about the second definition.

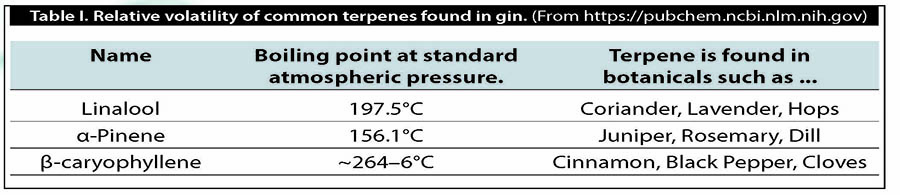

A brief aside on the chemistry of distillation: Gin and other botanical spirits are made by applying heat to a spirit in the presence of organic plant matter. When the ethanol is heated, it evaporates and recondenses. The compounds which give gin flavor also evaporate during distillation and recondense. If something is able to transition from the liquid phase to the gas phase (i.e., is able to be distilled) it is said to be volatile. Terpenes like pinene, linalool, limonene—to name a few—are volatiles found in plants that often contribute to the flavor of gin.

Reading Table I, we might say “α-Pinene is more volatile than β-caryophyllene.” But pragmatically, individual botanicals are complex and often consist of more than one volatile. For example, one study found 77 different compounds in Greek juniper cones (berries); even sweet oranges which are 94% limonene by volume have over 50 compounds in their oils.

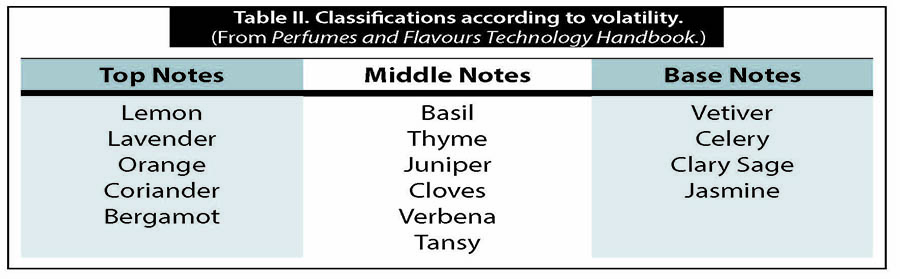

Perfumers have addressed this challenge by simplifying it. They divide ingredients into three categories: top notes, middle notes and base notes. Top notes are fleeting, light volatiles. These are what you smell the moment something is exposed to the air. After a few moments, you can begin to pick out the middle notes or the heart notes. In perfume, it’s after many hours you get the base notes; in spirits, it’s what you’re able to taste toward the finish.

Many perfume educators over the centuries have attempted to classify plants and compounds using this methodology.

Perfumers looking at Table II would likely ask the question, “How can I retain those light citrus scents?” To create a lasting citrus perfume, one might consider the role of fixatives.

But compared to perfumers, distillers are talking different orders of magnitude in terms of aroma: Perfumers are thinking in terms of hours and days on skin; distillers may be considering just as long as a cocktail sits in a glass or a bottle remains open. Yet might there be something from the literature on perfume that gin distillers can take with them to the still to create that lasting citrus-forward gin? Fortunately, the literature on perfume is rich with discussion of organic, everyday substances which have long been held to have a fixative effect.

Fixative substances

Throughout the history of perfume, the most important fixatives have been heavy, animal-derived products. Musk from civets and ambergris from whales are among those derived from fauna, however, distillers tend to draw their fixative heritage from the flora side of things.

In Piesse’s 1862 Art of Perfumery, he writes that a blend of crushed orris root and rectified spirits is “never sold alone, because its odour … is not sufficiently good to stand public opinion … But in combination its value is very great … it has the power of strengthening the odour of other fragrant bodies.” Perfumers were including orris root for reasons other than for its own aroma.

The Perfume Handbook, published in 1992, lists 42 separate botanicals with fixative properties. Orris root and angelica, the two most often cited by gin distillers as being fixatives, are both present; however, so are some other common gin ingredients, such as coriander and woodruff that are rarely—if ever—granted that status.

The “why” behind the mechanism of action and how these botanicals were identified as having fixative qualities is scarce. In Perfume Engineering, it is suggested that it is caused by “the physical properties of the fragrant molecules,” taking the previously simplistic categorization by relative volatilities and hypothesizing a chemical basis. “A partition coefficient of at least 3.0 and a boiling point of less than 260°C may be considered as having superior release properties.” Those substances with a higher boiling point may never volatilize. And according to Chemistry of the Sense of Smell, “Non-volatiles can act as odor fixatives.” Although present, their odor remains undetectable to humans.

Josh Meyer, founder of the perfume line Imaginary Authors, explains how he thinks about fixatives and molecules in his work creating and designing perfumes. “You could make a perfume with three different lemon oils and have different molecule sizes in each of those … and one of those is going to be your fixative. The definition is basically just your largest molecule that you’re working with. And that’s what’s going to stay around … they don’t dissipate as quickly … and they will also stay in your nose longer.”

Jan Hodel, a Ph.D. candidate at the Heriot-Watt University Center for Brewing and Distilling, explained the challenge with this model as it pertains to spirits. “Problem is, you talk about heavier compounds which serve as a fixative but they are usually less readily distilled. In perfume you work with extractives or synthetic compounds, non-volatiles directly.” Whereas perfumers have molecules of all different weights in their creations, gin distillers are already using a process that is biased toward filtering out non-volatiles and substances that are less easily volatilized. Jan adds there might be one exception—gin makers who compound their gin or macerate botanicals directly after distillation.

Dr. Anne Brock, chemist and master distiller for Bombay Sapphire, hypothesized that the Van der Waals force might be responsible for a fixative effect. In nearly all organic solids and liquids, these weak electric forces cause molecules to be attracted to each other. One physical effect of this is that substances held together with this force tend to melt at a lower temperature.

In Dr. Brock’s 2016 presentation at the Gin Guild Ginposium, she elaborated on how this might work. “We need to put in more energy into the system to break these bonds before the volatiles can escape … Just by the presence of these forces, we know that we have a greater energy contribution before evaporation can occur.”

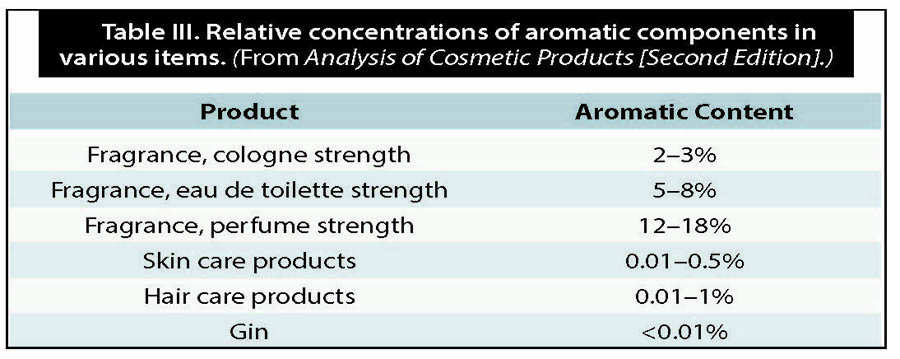

This would require sizable concentrations of fixative molecules in a liquid, such that they could interact with one another. However, gin is mostly ethanol and water. The concentration of aromatic molecules is incredibly low in spirits, especially when compared to perfumes, which are 12–18% by volume—the rest often being alcohol. According to the volumes detected in a 2005 study, the aromatic component is nearly three orders of magnitude smaller. In other words, in a distilled gin the likelihood of non-volatile and volatile molecules coming into contact with one another is less likely than in a perfume.

Table III

For centuries, it’s been held by perfumers that there’s a demonstrable qualitative effect of fixatives. The precise mechanism has not been fully explained. Studies emulating traditional perfume applications have found evidence that there is some sort of effect. On the other hand, those emulating mixtures where perfume is only a small component, such as soaps and detergents, have come up empty. One such study of linalool in soap found no evidence for reduced evaporation in the presence of higher boiling point materials.

The relative concentration of the “perfume” portion of a substance is what led Dr. J. S. Jellinek to conclude about soaps and other skin care products, “while fixatives are certainly effective on the perfume blotter, we cannot really expect them to do much in the sense of retarding the evaporation of other materials in most common perfume applications.” These other more common uses refer to the vast array of scented items in our everyday life, such as shampoos, cleaners and soaps. What these items have in common with perfume is that the relative concentrations of the aromatic portion in mg/L is much higher than that of gin.

Conclusion?

The literature on the topic of fixatives suggests that the effect in spirits and gin may not be big—or even there at all. But it’s important that we not take a literature review as a substitute for a formal study.

When asked about it, Jan Hodel stated plainly, “At the moment, there isn’t any published research done on [fixatives], at least not with gin in mind.” Dr. Anne Brock similarly doesn’t think we should rush to a conclusion. “All the research that is out there on the internet comes from the perfume industry … I know there’s a lot more analytical work here to be done.”

Furthermore, even in a profession where there is a tradition of considering fixatives in the design process, perfumer Josh Meyer explains that the process is still more artistic than analytical. “It’s just simply finding things and blending them together to get the desired effect. And that’s what takes so much time … it’s a little bit like cooking and it’s a little bit like painting.” Even with fixatives, he adds, “Trying those things out is literally the job.”