For those who live in western Pennsylvania and love whiskey, it is impossible to escape the history of the rebellion against an excise tax that happened here. Pieces of the story are scattered in museums, cemeteries and reenactments. Anyone who visits Pittsburgh and its surrounding counties will meet folks who continue the customs and crafts of that time with great pride.

Many western Pennsylvania settlers emigrated from the British Isles, where taxes had traditionally only been levied on landowners and foreign goods. In 1643, Britain imposed an excise tax on ale and cider to cover the cost of a recent war. A year later, the British government imposed a tax on beef, salt, rabbits and pigeons. The ensuing tumult and riots over the taxes were violent. Mobs burned buildings in London and killed tax collectors. But the list of taxed

items only grew. And so did resistance, which was greatest in Scotland and Ireland, where people drew little benefit from the government. When taxes became uncollectable, fines were levied. Those who couldn’t pay were imprisoned or enslaved.

These excise taxes became very lucrative. But it wasn’t good for everyone. Large distillers favored the tax, as it served to drive out smaller competitors. The greater the resistance of the small producers, the greater the penalties. Seizure of properties increased. Greater numbers were enslaved and imprisoned, and corruption among tax collectors was rampant.

It was in this violent context that Scots and Irish emigrated to the New World colonies and moved far to the west, settling in wooded mountains with plenty of fresh water at the confluence of the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers—the source of the Ohio River. Here they hoped to live happy and tranquil lives. They made whiskey again.

The area, known as the Forks, and surrounding settlements were identified by the streams that fed the three rivers. There were many, including one, Mingo Creek.

Enter the Stamp Act of 1765.

The residents of the Forks were horrified. It appeared that the reach of the British tax collector had arrived. Many joined the Pennsylvania Militia and fought in the American Revolution. After the Revolution, the war-weary returned to find that much of their land had been lost to Canadians and Native Americans. But the English and their taxes had been stopped. The new U.S. Constitution gave the government no authority to levy excise taxes. It was time to make whiskey.

Hamilton Goes Upside Down

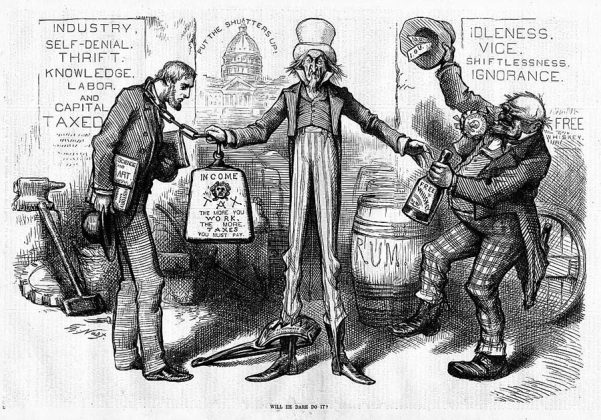

The Revolution had been sustained by individual fortune, largely that of Robert Morris, a financier. The soldiers in the war hadn’t been paid. The army wasn’t being paid and was threatening mutiny. George Washington was nearly bankrupt. When Morris was named superintendent of finance in 1781, he proposed opening a central bank to levy a national tax. In 1782 the Bank of North America was established, again with heavy backing from Morris. Alexander Hamilton, working with Morris, convinced the House of Representatives to levy poll taxes, land taxes and an excise tax—on whiskey. The Whiskey Excise Tax passed on January 27, 1791, and became law that March. As in England in 1643, whiskey was being called on to pay off a war—this time in the United States.

Hamilton and Morris celebrated with shots of whiskey.

The farmers at the Forks continued to receive no benefits from their new government. They were strong and industrious people, though, and prospered. In March 1791, there were 272 licensed stills around the Forks. Whiskey had become an important part of life. There was demand on the East Coast and packhorses were driven there, returning with supplies. Even with loss of land and fortune, whiskey helped the farmers at the Forks survive.

However, the excise tax equated to one-quarter the price of whiskey. The farmers were outraged, the tax being reminiscent of the excise taxes imposed in England and battled by their forebears. They were not alone, as petitions to repeal the tax were sent to Congress by all the colonies. In August of 1791, some of the farmers met and adopted a resolution that classified excise officers as public enemies and declared that no one was to communicate with them or offer them comfort in any way. To show their unity, the farmers returned to their farms and erected “liberty poles.”

These liberty poles were nothing more than bare tree trunks to which were affixed muslin ribbons stained with the words “No Excise Tax.”

And anyone happening on a portrait of Alexander Hamilton flipped it upside down in defiance of his plan.

How It Began

In September of 1791, a meeting was held in Pittsburgh. Attorney David Bradford, from Washington County near Mingo Creek was there, joined by 10 men from nearby settlements. They adopted a resolution stating that the tax was subversive to liberty and discouraging to agriculture and manufacturing. People were strongly urged not to accept positions as tax collectors in hope that the law would become ineffective.

General John Neville, a war hero and wealthy landholder at the Forks, appreciated the government’s situation. He had built a magnificent mansion near Bower Hill and owned the largest still in the area. Congress appointed him to be Revenue Inspector, and he appointed a local farmer, Robert Johnson, to collect taxes near the Mingo Creek settlement.

As Johnson rode along Pigeon Creek, he was attacked by 16 men with painted faces, disguised in women’s clothing. They dragged him from his horse, cut off his hair, stripped him, poured hot tar over him and covered him in feathers. They left him severely burned and stole his horse. He managed to crawl away through the woods, and by the next morning had returned to his cabin. Johnson was able to identify several of his attackers and he convinced a judge to issue arrest warrants.

The deputy sheriff, fearing for his life, hired an illiterate cattle drover to deliver the warrants. Arriving at one of the farms of the accused, the drover was whipped, tarred, feathered and chained to a tree.

Can’t Avoid the Taxman

Neville remained loyal to his office and requested armed forces to help collect the tax. No troops were sent. No taxes were collected. And no further violence ensued. Neville, however, grew weary of being threatened and shunned by his neighbors and informed Philadelphia that “I shall be obliged to desist further attempts to fulfill the law.”

Another meeting was called in Pittsburgh, and Bradford helped shape a strong resolution against the excise tax. It was sent to Congress with the intention of bringing peace to the Forks.

Hamilton, though, was convinced that the people of the Forks would continue to violate the law. He did not want anyone evading taxes, for fear their disobedience could spread and the tax would never be collected. He argued that Neville must collect the taxes and convinced President George Washington to issue a statement of warning to “fire a shot across the bow.”

Hamilton was right. The violence grew worse. In March 1793, tax collector Benjamin Wells was attacked in his home. Eight months later, he was invaded again. Men in disguise ordered him to produce his records and publish his resignation or be killed. When they left, Hamilton was hanging upside down.

Smaller farmers who feared imprisonment traveled to the Neville mansion to pay their taxes. In their absence, rebels would “mend their stills” by shooting holes in them. Notes were left threatening worse, famously signed by “Tom the Tinker.” Shortly after, a liberty pole would generally appear to indicate the farmer had gotten the message.

In February 1794, the farmers formed the Mingo Creek Society.

In June 1794, Bradford went to New Orleans to watch barges arrive and personally ensure that shipments arrived in full. It seemed that every time 10 barrels left on a barge, nine or so arrived at the ship waiting for them. He was, therefore, not at the Forks when the United States Marshal arrived.

After Neville reported more violence, Alexander Hamilton directed Attorney General Edmund Randolph to issue some 30 arrest warrants for those who resisted paying the tax. These warrants were to be delivered by United States Marshal David Lenox. At news of his approach, the farmers became incensed. When Neville brought Lenox to the Miller farm on July 15 to serve a warrant, the Miller family shot at the two men and scared them off.

The Mingo Creek Society decided to capture Lenox while he was at the Neville mansion. On July 16, they traveled to Bower Hill. Words were exchanged and shots fired. Soon, 500 men under war hero James McFarland rode to Bower Hill determined to capture Lenox and destroy the arrest warrants.

Neville received word of the approaching insurgents and called for protection. Major James Kirkpatrick sent Neville, his family and Lenox to Pittsburgh and barricaded the mansion. The 500, marching to the cadence of drums, arrived at 5 p.m. on July 16 and found the house occupied by soldiers. They set fire

to surrounding buildings, demanding that Lenox come out.

As the fire grew close to the mansion, Kirkpatrick waved a white flag out the second-story window, begging the insurgents to spare the house and its treasures. When McFarland stepped from behind a tree to accept the surrender, he was shot and killed on the spot. The mansion burned to the ground as the soldiers fled.

Seriously, a Picnic?

James McFarland was much loved and the Mingo Creek militia felt justified in what they had done. Bradford, just back from New Orleans, believed that their actions were necessary and violence should be answered with violence. State Assemblyman Hugh Henry Brackenridge of Pittsburgh, however, insisted that the men had committed high treason and that the president should call out the army against them. But first, President Washington would have to be notified. Bradford plotted to steal the mail going from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, and then did.

When the mail was opened in the back of the Black Horse Tavern on July 26, 1794, Bradford learned that several letters had indeed been sent informing the United States government of what had happened at Neville’s mansion.

The letters were destroyed and more whiskey was ordered. It was decided that the Mingo Creek militia would meet at Braddock’s Field on August 2 and demand the people of Pittsburgh produce Major Kirkpatrick, General Neville and other tax collectors for expulsion from the city. The merchants of Pittsburgh feared they were coming to burn buildings and made a public display of banishing the men who had written the letters to Philadelphia. The militia set up camp in Braddock’s Field. Bradford attempted to negotiate, but none of the wanted men were released to the insurgents and none of the Mingo Creek militia retreated.

There were 7,000 men assembled at Braddock’s Field. Most had no land. About a third of them owned stills. They were poor, and their grievances were economic. They united around the martyred James McFarland, who they believed had lost his life defending them against an unfair tax and a tyrannical government.

While encamped, a small band painted their faces and crossed the Monongahela River, where they burned down the home and barns of Major Kirkpatrick. They erected liberty poles on the properties of tax collectors, brutalized them and burned their barns. The violence spread into Virginia, Maryland, Ohio and central Pennsylvania, with liberty poles erected along the roadways. Slogans attached to the poles proclaimed liberty, equality, fraternity and no excise.

A committee of merchants formed in Pittsburgh. They rode out to Braddock’s Field with barrels of whiskey and mounds of excellent food and advised the militia that buildings don’t burn selectively—all of Pittsburgh could be lost. They also reminded the militia that there were cannons at Fort Fayette that could be fired in defense.

The 7,000 lost their nerve, and after a wonderful picnic, dispersed.

Once It Got Rolling, It Was Tough to Stop

On August 14, 1794, 250 delegates from six counties met at Parkinson’s Ferry. The intent of the gathering was to prevent the adoption of any more criminal resolutions. They agreed to petition Congress to repeal the excise tax and replace it with one less odious, to be cheerfully paid. After the meeting a liberty pole was erected. Benjamin Parkinson nailed a sign to it, reading “Equal Taxation and No Excise. No Asylum for Traitors and Cowards.”

It was a little too late.

Word reached President Washington that a large contingent in North Carolina was now organizing and settlers at the Forks were still violently opposing the Whiskey Tax. The president feared a frontier-wide separatist movement and put out the call for troops. To set an example, he targeted a small group of rebels—the farmers around the Forks.

Washington dispatched a peace commission to Pittsburgh. They were met along the way with liberty poles. The commission wanted a resolution from the rebels stating that they would submit to the law. When they arrived at Parkinson’s Ferry, the meeting was brief. The rebels appointed a committee to carry their own resolution to Philadelphia, stating that they would do no such thing.

President Washington ordered 12,950 militiamen into western Pennsylvania. Meetings were held to discuss the law. Opinion was changing and the votes at each meeting were leaning more and more in favor of ending the insurgency. But Bradford urged the men to remain strong and fight on. Bradford, likened himself to the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre and called for the bringing of the guillotine to America in a Reign of Terror. There were calls for secession from the Untied States and possible alliance with Spain, which controlled the territory south.

Liberty poles continued to pop up further away from the Forks. Politicians were hung in effigy, and tax collectors in other states were attacked by men with painted faces. Riots broke out. Up went more liberty poles with the slogan “Liberty or Die.” Some attempted to chop down the poles and drive the rebels out. Tom the Tinker, disappointed at the sway in opinion, began posting threats again.

Run for Your Life

On October 11, terrified residents of the Forks met with Washington, hoping to convince him to turn the army around. They told him of changing opinions in favor of submitting to the tax. Washington pointed out the presence of liberty poles and the continued rioting, and pressed on. Convinced that things were going well, he returned to Philadelphia, handing off command to General Henry “Lighthorse Harry” Lee, a revolutionary war hero and father of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. The rebellion scattered in the face of the oncoming army.

Word reached Bradford that the army was approaching. Knowing he would be charged with treason, Bradford fled with the clothes on his back, leaving his wife and children behind. He was able to escape to Spanish territory. The army arrived at his home the next day.

Where Is Everybody?

Residents of the Forks begged General Lee to relent in light of changing public opinion, but Lee refused, saying they were only complying because of the army’s presence. Alexander Hamilton arrived to begin the arrests and interrogations. Many under suspicion prepared to flee.

By early November, it was clear that resistance against the army was futile. Alexander Hamilton and General Neville compiled a list of suspects, even if the only charge was raising a liberty pole.

What became known as the Dreadful Night occurred on November 13, 1794. Those on the list in Mingo Creek were dragged from their beds, marched to the Buck Tavern and thrown in the basement without water, food or heat for two days. They were then marched to the army’s quarters for trial and put in open pens. It was raining and muddy and cold.

It became obvious that none of those rounded up were major players, and most were released. The army began the long trek back to Philadelphia with a few prisoners as scapegoats. They were paraded through the streets while the bells of Christ Church pealed victory, then marched past President Washington’s house while he watched from the porch.

When the dust had settled, the rebellion was squelched, scores of people were convicted in local courts for assault and rioting, but only two men were tried and convicted in federal courts. The two rebels, Philip Wigle and John Mitchell, were sentenced to hang but later pardoned by Washington, who referred to them as “an imbecile and an idiot.” Within six months all the prisoners had been released.

Pittsburgh went quiet after the army left. There is no record of further distillation until 1810. (Wink, wink.) There is no record of the Whiskey Excise Tax being collected after the rebellion.

Thomas Jefferson later commented that, “A rebellion was declared, armed for, marched against, and never found.” When Jefferson became president in 1801, the Whiskey Excise Tax was repealed, with a promise to never impose internal taxes again except in the event of a national emergency.

David Bradford’s original house has been preserved as a historic landmark where historians in period costume reenact events of the rebellion. A new liberty pole has been erected in the garden behind the house, with three rags tied to the top reading: No Excise Tax. Bradford returned home briefly, then moved to New Orleans, where he lived out his life.

And now, whiskey has returned to the Forks, with Mingo Creek Craft Distillers making Liberty Pole whiskeys.