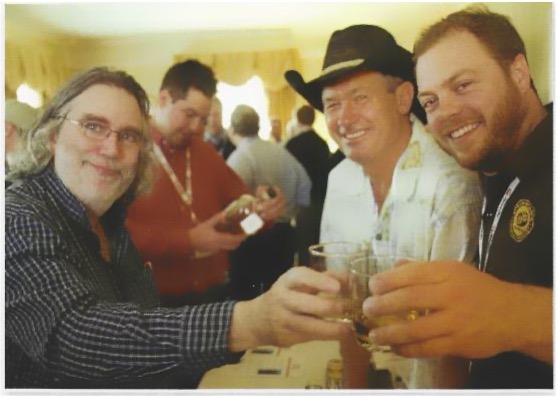

I have always wanted to be a distiller. Though I started homebrewing in 1990, when the craft beer revolution was heating up, I could tell pretty quickly that professional brewing was not for me. Distilling, however, the hope of making my own Bourbon, my own Scotch-inspired usquebaugh, held a real allure. Today I’m a wine and liquor retailer, and the still continues to fascinate me. So it was with great excitement and high hopes that I attended the 2008 American Distilling Institute Whiskey Conference in Louisville, Kentucky. And between the camaraderie of kindred spirits, plenty of tasty dramming, and the pure passion inherent in a handmade product, my time spent was amply rewarded during this fabulous whiskey tinged gathering.

One highlight of the conference was the host, Huber Winery and Distillery, in Borden, Indiana. I rode the bus to Huber expecting a li’l ol’ country winery with a still in the corner and some picnic tables. I found 550 acres of agrotourism, with a huge convention space and an extensive winery/distillery, and multiple barrels of various fine spirits (and outstanding food, including some of the best fried chicken ever.) Huber has partnered with ADI on several conferences, and judging from their stunning performance in this one, 2008 surely won’t be the last.

A clear sign that American craft distilling is growing up was the presence of Jim Murray, probably the world’s leading whiskey writer. Jim was in town to lead the whiskey judging, but also to conduct a tasting with the conference attendees. And what a tasting it was, by turns informative, thought provoking, and cunning, as Jim surprised us all with peaty-smoky whiskies from Oregon (courtesy Jim McCarthy) and, of all places, India. Jim served notice that superb whiskey can be made anywhere, from Scottish glens to Kentucky hollows to the Indian subcontinent and certainly in fifty American states.

The plan and schedule of the conference was brilliant (though not immune to a bit of controlled chaos, to be expected in any gathering of some 200-plus distilling enthusiasts). There was something for everyone, with seminars aimed at either those who are thinking about distilling, or those who already have product coming off the still. The information provided to would-be distillers was thoughtful, covering such essentials as licensing, production, whiskey styles, marketing and more. I was glad to see plenty of attention to specific whiskey topics, such as mashing inhouse as opposed to contracting with a brewery.

I was privileged to participate in a discussion about selling and distributing spirits, part of a panel of several distillers led by Sonja Kassebaum of North Shore Distillery (whose products I am pleased to sell). Ralph Erenzo of New York’s Tuthilltown Distillery was part of the panel, and is a true Yankee in the old sense of the world, filled with ingenuity, smart business sense, and passion for his product. Ralph’s range of spirits, including a rye whiskey and “Hudson Baby Bourbon” in irresistibly cute half bottles and New York State apple vodkas, is a solid product line of classically inspired American spirits.

On the other hand, Rick Wasmund of Virginia’s Copper Fox Distillery makes a totally unique whiskey, a fascinating single malt that bears only a faint resemblance to the malts of Scotland. I met Rick (whose product I am also pleased to sell) over dinner on the first night of the conference, and was immediately struck by his conviction to do things his way. Rick not only mashes his own barley, he even malts his own grain, drying it with American-style smoke woods like apple and cherry. I know of one other distillery in the world that malts all of their own grain — Springbank of Campbeltown, Scotland’s most traditional distillery and one of its best. When a distiller is mentioned in the same sentence as Springbank, he’s got to be doing something right. Rick’s whisky is by turn smoky and pungent, sweet and fruity, intense yet well-balanced, a raw youngster yet but with tremendous upside. This is the promise of American craft distilling: the discovery of new whiskeys, spirits that speak to the uniqueness of a place and the impassioned hand of a maker, original drams not following in another’s trail.

From the retail point of view, I consider American craft spirits a growing category in the liquor marketplace, albeit a small niche at present. Many craft distillers focus on their home market, selling successfully as the cool local distillery (following in the steps of craft breweries, who also found good sales at home). Regional or national markets, however, can be a tougher nut to crack. Here, I think the cream will rise to the top.

To grow beyond a local market, a craft distiller has to set herself apart with compelling and distinctive flavor (and a great package is important, too). Outside of its home market, a redistilled, thrice-filtered grain neutral spirit sold as craft vodka will have a tough time convincing a consumer to put down the Grey Goose. At The Party Source in Bellevue, Kentucky, many of the staff rate California’s Hangar One as our best vodka, flavored or otherwise. We sell a goodly amount of Hangar One, and it has turned into one of our core brands of vodka. We never sell it based on its California location. We sell it on flavor. Other examples of compelling white spirits include the Thibodeau brothers’ Cold River Maine potato vodka and Duncan Holaday’s Vermont Spirits maple and milk vodkas, all of which have a great story and are made from scratch with local products, reflecting the native flavor of the land from which they spring.

In fact, as craft spirits go, I suspect whiskey and other brown spirits will have long legs in this young movement. Whiskeys and brandies and aged rums are supposed to taste different from one another, while vodka to some extent is not. While it might be harder, and certainly more expensive, to make an aged spirit than a white one, it is easier to make a brown spirit different from its peers. Further, drinkers of straight brown spirits are, broadly speaking, more apt than vodka cocktail drinkers to try a new product based on flavor. On a store shelf, a craft American whiskey stands out, while craft vodka faces a much more crowded field with scores of products from around the world.

If brown spirits are in the ascendancy in craft distilling, then I am sure the 2009 ADI Brandy Conference will be a winner, not least because I have visited the host, St. George Spirits in Alameda, California, and found these mad scientists to be eminently hospitable. And I look forward to future Kentucky-based whiskey conferences in my neck of the woods. In the meantime, craft distillers should know that this burgeoning industry is receiving attention from the upper levels of American liquor retailers, distributors and, increasingly, the American consumer. Like Rick Wasmund’s home- malted four-month-old whisky, it is still a young movement, but one with real quality and the unmistakable imprint of passionate American entrepreneurs. In Germany, the distillers’ guild says “Prosit,” and the Scots say “Slainte,” but here in America I say simply cheers to your small stills, your conviction, your craft.