Over the past decade, large clear ice cubes have become the standard at better cocktail bars across America. They can come in two-inch cubes or rectangular “spears” for Collins glasses, or be carved or pressed into spheres and other shapes. They look fantastic compared with cloudy cubes, make even the simplest cocktails look mixology-fancy, and often earn the free advertising that comes from visitors sharing Instagram pics of the drinks at your bar.

On the other hand, an in-house clear ice program can take up a lot of space, require a rather large initial cash outlay, and involves ongoing time and effort. Purchasing clear cubes from specialty cocktail ice providers can be expensive depending on order quantities and proximity to the supplier. But there are options for creating a big ice program to suit the size of your venue.

A Small Big Ice Program

Automatic ice cube machines from companies like Hoshizaki and Kold-Draft typically top out at 1.25-inch cubes. Larger ice requires manual labor to produce, and that is the kind we’re concerned with here.

A very hands-on way to make large, clear ice in a standard freezer is by taking advantage of “directional freezing.” When water freezes into ice, the forming ice crystal lattice rejects air and any impurities in the water, which are pushed away from the point of freezing. A typical ice cube freezes from all sides toward the middle of the cube. The air and impurities are pushed into the center, eventually forming a cloudy core. Expansion of the ice during freezing causes cracks that magnify the cloudy look of cubes.

To make clear ice without a cloudy center, we can force the water to freeze from the top of the cube down toward the bottom. The method I developed in 2009 for doing this involves filling a hard-sided cooler with water and putting it into the freezer with the top off. Because of the insulated sides and bottom, the water will freeze from the top down, rather than from all sides toward the middle. This is known as directional freezing — controlling the direction in which water freezes.

To make clear ice without a cloudy center, we can force the water to freeze from the top of the cube down toward the bottom. The method I developed in 2009 for doing this involves filling a hard-sided cooler with water and putting it into the freezer with the top off. Because of the insulated sides and bottom, the water will freeze from the top down, rather than from all sides toward the middle. This is known as directional freezing — controlling the direction in which water freezes.

Only when the last one-third or so of the water starts freezing does the ice become cloudy in that section, as the trapped air has nowhere else to go. To harvest only clear ice, remove your cooler from the freezer before the cloudy part begins forming. Or you can let the entire block freeze and hack off the cloudy ice on the bottom.

But you want ice cubes, not a cooler-sized slab of clear ice. You can cut up one slab at a time using a bread knife, ice picks, and other hand tools. Or you can buy a ready-made clear ice cube tray that takes advantage of directional freezing: A silicone ice cube tray with 2-inch compartments hangs inside an insulated container, and each cube compartment in the tray has a hole in the bottom. When the ice freezes from the top down, it pushes the trapped air out the hole and into the reservoir of water below the tray. When it is fully frozen, pry the tray off the surface and empty the cubes.

Many brands of clear ice cube (and ice sphere) trays have come onto the market in the past several years. The brand Ghost Ice makes probably the largest one. It is designed for heavy use and produces 48 cubes (2 x 2 x about 2.5 inches) per batch in about two days in a large, shallow, insulated cooler. It costs about $350 and fits in a walk-in freezer or chest freezer but not a standard-sized freezer. There are also smaller sizes of this same tray. Other clear ice trays optimized for home use make 12, 10, or fewer cubes per batch in about a day.

It is possible to build a clear ice program using racks of multiple coolers or clear ice trays. Some smaller cocktail bars make all their craft ice this way. It requires regularly emptying and refilling trays (and potentially cutting slabs into cubes), which can be done as part of daily prep work. But, importantly, this scheme takes a significant amount of freezer space to hold all the coolers.

A Big Big Ice Program

Most big cocktail ice is made using ice sculpture block machines. First, giant blocks of clear ice are produced in special machines, and then the blocks are manually cut into cubes and other shapes.

Though there are a few companies, including Polar Temp, that make these ice block machines, the Clinebell Equipment Company seems to be the most popular choice. Their CB300 model produces two 300-pound blocks every three or so days, each sized 20 x 40 x 10 inches. Machine prices vary, but Joe Willeford of Clear Ice LA says he paid just over $10,000 for the CB300 and accessories, including delivery to California, earlier in 2023.

The machines have cold plates at the bottom and water pumps near the surface to prevent the water from freezing on top. The ice forms from the bottom up toward the surface. There is no trapped air this way, and no cloudy ice left at the surface; just some water with minerals and other impurities that needs to be suctioned off using a shop vacuum. Once frozen, the large blocks are pulled from the machine using a hoist of the type to remove car engines. (The hoist is another expense to figure into price and space calculations.) Some other ice block machines, including one from Ice Max, open at the side, allowing blocks to slide out without a hoist.

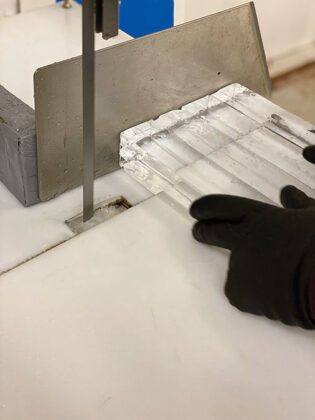

Ice company employees next cut the large block into large slabs with an inexpensive electric chainsaw with a guide on it; the type you’d use to cut planks from a log. Then, using a (food-grade) band saw, they cut the slabs into straight-sided cubes and tall spears for drinks in Collins glasses. (Some companies say they skip the chainsaw step; their band saws must be quite large.) You can find videos of this process on YouTube and Instagram — it goes surprisingly quickly and is very satisfying to watch.

Jimmy Yeager of the now-sold Jimmy’s An American Restaurant and Bar in Aspen has been making and cutting ice for years and continues to supply cocktail cubes as well as make ice displays with frozen bottles and other objects. He is able to cut about 800 two-inch cubes from each 300-pound block. He estimates that the process of breaking down two blocks, including harvesting, using the chainsaw, and cutting cubes with a bandsaw can be completed in three hours with two people working together. He estimates including labor, electric, and water, the cost is about 12.5 cents per cube to produce 1,600 cubes per session.

These ice sculpture block machines do not need to be kept in freezer temperature rooms, and cutting can also be performed at ambient temperatures. After cutting, the cubes can be stored in a regular upright or horizontal freezer until needed. In other words, you do not need a walk-in freezer to have a big ice program, but you’ll need a little floor space for the machine, hoist, and cutting table. (Note that depending on your region, regulations on food preparation safety may necessitate specific licensing and equipment.)

Other Ways to Make It Work

In the past few years, both the Clinebell company and BF Tech have released machines that produce smaller (25- and 60-pound, respectively) blocks of clear ice. They each produce several of these blocks in one or two days, with the resulting blocks light enough that they don’t require a hoist and can be cut with saws or other manual ice tools if desired. They produce less ice per batch and were designed to serve smaller operations.

In some markets, ice sculpture companies sell the full 300-pound blocks or smaller ones directly to businesses. These can then be cut in the kitchen/distillery without the need for the ice block machine. The downsides include uncertainty of block delivery times and the expense of the block, but block delivery might be a temporary way for some distilleries to test the process before investing in an expensive machine.

At the Bar and Out of the Shop

Several cocktail ice provider companies began as the in-house ice program at bars. After producing more than enough ice for their own venues, they began selling it to other bars, and spun the ice business off into a separate entity. In some cases, these companies have become massive, providing ice to accounts like multi-venue hotels and casinos.

Still other ice manufacturers sell their big ice cubes and spheres at retail, mainly in larger liquor stores. It is often packed into bags or cardboard tubes, and pricing seems to be just under $2 per piece for packs of a dozen cubes. Selling at retail sometimes allows for this ice to be delivered to homes by companies like Uber Eats and Instacart.

Of course, the easiest way to serve drinks at your tasting room over big ice is to purchase it in bulk, already cut and ready. (Pricing for two-inch cubes varies widely by region, anywhere from $1.50 to $0.35 per cube in bulk, including delivery. Spheres, spears, and other shapes cost more.) Today, most large- and mid-sized markets have cocktail ice providers, and prices have come down significantly in many markets due to increased competition.

The first step to starting your big ice program should probably be to find out how easy and/or expensive it is to simply outsource it. From there, you can make a plan to grow into the program that suits your needs and space. There’s no reason any size bar can’t have some kind of ice program to impress its customers.

There is more to ice than cubes. Big clear ice can be cut into shapes, like diamonds and spheres, by hand (this takes some skill), using an ice ball press that melts larger ice down into shapes, or with a computer numerical control (CNC) machine. Sculpture and cocktail ice companies use CNC machines to carve deep, clear logos and designs into ice cubes and blocks as well. Objects like bottles and bouquets can also be frozen into blocks of ice by anchoring them in place in the block maker while the ice forms around them. Ice companies sell these custom engraved cubes and blocks for corporate parties, weddings, and other events.