When I took my first steps into the world of whiskey, let’s be honest: The whiskey was its own reward. But part of the lure for me was also the history. There were tales that I wanted to learn. There were stories of distilleries stretching back centuries. Who owned them? Who developed the style that drove the whiskey’s popularity? Who carried that legacy to the present day?

Unfortunately, in the world of American craft spirits, people of color cannot tell that tale — at least, not yet. There were people like Nathan “Nearest” Green, who played a role in creating Jack Daniel’s, one of the biggest brands in the world, but he wasn’t an owner and his legacy was not commonly known. He was an important part of the tale, but it wasn’t told as his story.

With the efforts of people like Fawn Weaver (remember that name, because you will hear it aplenty) and programs like Diageo’s Pronghorn partnership, which seeks to invest “financial, individual and network capital” to “support, grow and sustain Black-owned businesses in the spirits industry,” there is a clearer path forward for those who seek to make their own legacies in the craft spirits industry.

I had the pleasure of speaking to a group of Black professionals — former scientists, engineers, lawyers, and executives — who are making their own bold mark in the world of spirits. I talked to them about their time and experiences in the industry, what they learned, and what they are thinking right now.

Why right now? Doors are opening. Opportunities are presenting themselves. New players are stepping onto the stage. The explosion of craft distilleries all over the country has made it easier for people to distill and thrive in their home states, and this rising tide has begun to make waves in the Black community.

[I would like to give a special thanks to those who participated for their time and knowledge. Interviews have been excerpted and edited for clarity.]

How did you get into the world of spirits?

Todd Buckley, founder of Destiny Spirits, lecturer in social media and consultant within the craft spirits industry: In 2008, Washington State changed the laws to make it much easier to open a distillery. I was burned out from being in the tech sector and was looking for something that would combine enjoyment with income. I started studying and getting involved in every aspect of the craft industry I could.

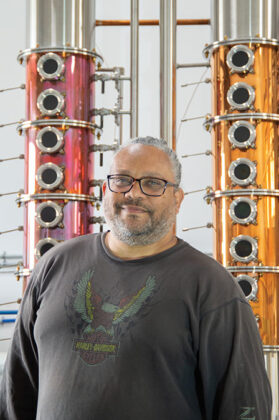

Ron Gomes, co-founder of Painted Stave Distilling in Smyrna, Delaware: In 2009, I was introduced to craft distilling by a fellow faculty member, and I attended my first craft distilling workshop in 2010. It was at this workshop that I connected my bench science to craft distilling and saw lots of possibilities.

In 2011, with my wife’s blessing and steadfast support, I left my College of Medicine career to open Delaware’s first stand-alone craft distillery. Together with my business partner, Mike, we spent the next two years changing laws, pooling funds, raising capital, finding a suitable location, renovating our space, and learning how to craft our products before opening to the public for the first time in 2013. Over the last nine years, we’ve grown from a team of two to a team of 34 and have built a destination distillery along with two food trucks that serve as an anchor in the community, while producing numerous award-winning products which enjoy distribution in 10 states.

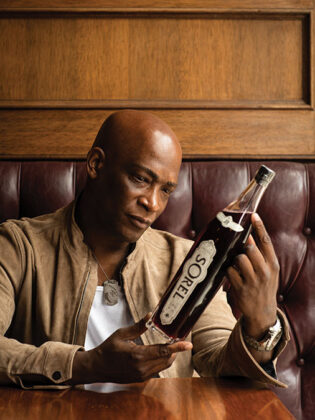

Jackie Summers, creator of the award-winning Sorel Liqueur: In 2012 I had a cancer scare. My doctor found a golf-ball sized tumor inside my spine, giving me a 95% chance of death and a 50% chance of paralysis. Surviving permanently adjusted my perspective. I chose to leave 25 years as a corporate executive to pursue my dream of day-drinking, professionally. When I couldn’t figure out who was going to pay for my preferred lifestyle, I decided to launch a liquor brand. I took a beverage I’d made in my kitchen for almost 20 years and became the first person to successfully create a shelf-stable version of a 500-year-old Caribbean favorite beverage.

Drew Fox, owner and founder of 18th Street Distillery and Brewery: My uncles and grandfather gave me my first introduction to whiskey. Every Christmas they would sit in the front room eating canned salmon and playing spades while talking shit about their wives and drinking whiskey. They each would bring a bottle. It was always Crown Royal, Jack Daniel’s, and White Label brand (Dewars). One year they all got blasted and my uncle Vincent looked at me with his red glossy eyes and said, “You want a pull?” I said “Yep,” after waiting for many years of watching these fools drink this brown stuff. I took slow sips. I just remembered brown sugar, and that day fell in love with Jack. Crown, not so much.

Chris Montana, co-Founder of Du Nord Social Spirits: I got into it and made my way as best I could. When we were starting in Minnesota, there were no micro distilleries. I had an interest in it because I’ve been brewing beer for a long time. I didn’t have anyone to look to when I first started it. I had made the decision and already had an agreement on a place. I started going to many distilleries. I went to 45th Parallel, which might as well be a Minnesota distillery but because of the laws it started next door in Wisconsin. But yeah, I really hadn’t done much other than research and books, which is kind of where I live. And so that’s where most of my information came from. There was certainly a lack of people who look like me. I didn’t know that there were no people who look like me doing this.

Did you have a role model when you started your spirits journey?

Buckley: Steve McCarthy from Clear Creek and Hubert Germain-Robin.

Gomes: At the time, I did not have role models in the industry; however, there were a number of folks that appeared to be doing something right: John Little, Lance Winters, Don Poffenroth, Todd Leopold, and Karen Hoskin, to mention a few.

Fox: I wish I had a role model when I started. The whiskey business has long been full of generations of white men with long money. Very few would let folks like me in that network, but I will say my good friend Bill Welter at Journeyman Distillery helped change my mind on that way of thinking. From day one when I told him I wanted to open a distillery he welcomed me with open arms and helped me in so many ways that a thank you just wouldn’t be enough in my eyes. He’s just good people.

Summers: I had no prior experience in hospitality prior to launching Sorel, my brand, in the spring of 2012. Arthur Shapiro, former CMO of Seagram’s, adopted me as his mentee. In the past decade I have benefited greatly from his tutelage.

Vanessa Braxton, CEO and President of Black Momma Vodka & Brands: I’m going to say yes. Everybody else that was in the spirits industry was a role model for me. I learned a lot from Koval in terms of distilling and the art of cuts, and we are friends to this day. It’s just an amazing field where I have been able to hone my skills and create so much with my brand right now.

Right now, who or what in the industry inspires you?

Buckley: I love seeing the industry becoming more inclusive and innovative. There isn’t a single person, per se; however, I do find it great to see more people from different backgrounds getting involved in craft spirits.

Braxton: Lisa at Widow Jane. Seeing how Nicole Austin started at Kings County and moved to Dickel. I have watched her from afar. So many women actually distilling have inspired me. Also, a friend of mine, Josh Morton; we’ve been friends for almost 10 years. The same thing with Paul from FEW. There are a lot of people that inspire me to keep on going, to be able to craft releases. I like seeing what others are doing because it inspires me to do more.

Gomes: The fact that I know so little. There’s always something to learn, there’s always another question that is generated by the answer. That’s so cool!

Fox: My team inspires me. It’s very hard for people to believe in your vision and dreams when they have visions and dreams of their own. Every day I try to give each of my team members a path to work on their dreams with knowledge, work ethics, tools, and training. I want them to be driven by the motivation to always be the best at what you do and hold yourself to a high standard. No matter how much money you make, you should hold the line in good and bad times. Stick to your standards and inspire others to do the same.

Summers: The indefatigable Fawn Weaver, CEO of Uncle Nearest, continually inspires me. She strives for legacy while helping others achieve their goals (often quietly) not as a PR stunt, but as part of a core belief that we succeed together.

What is the hardest lesson you’ve learned while working in spirits?

Montana: The hardest lesson for me had more to do with my own naivete when I came into the industry. My focus was not on being the Black owner of a distillery. My focus was 100% on the quality of what was in the box. I thought that nothing else mattered. All that crossed my mind was if I made something that was good, I could have a successful business. I learned that being successful in this business is so much more than that.

Buckley: It is incredibly difficult to raise money unless you already have money. It is much easier to make spirits than sell spirits.

Fox: If you don’t hold the people who work with you accountable, it will have long-term consequences on team morale.

Gomes: Admittedly, I was unaware of the absence of diversity and equity in the craft-distilling industry. In fact, if it wasn’t for the social unrest and awareness efforts that followed the murder of George Floyd, I may still be unaware of my “place” in the craft-distilling industry. Stemming from interviews with writers and bloggers, I’ve come to learn I am the only person of color (POC) distiller in Delaware but may also be the third POC to ever receive a Distilled Spirits Permit from our federal government.

Braxton: Watch your money. You can’t grow very quickly overnight. You know, trying to hit 30 markets all at once? You don’t have the money for that. You have got to learn to focus. I learned to focus, which helped my brand and helped me work better and more efficiently. When it came to distilling, that was a lesson. I spent a lot of money in the beginning but then reeled it back. And I also learned that I have to have my own place, my own distillery to work in. When you work at somebody else’s facility and it’s not yours, that gets old really quick, because I know how I am. I like to have my own.

Summers: The people who have the power to change things for the better often use that power to maintain the status quo. My existence as a Black-owned brand is disruptive, and disruptors are frequently punished.

If you could talk to your younger self, what advice would you give?

Buckley: Study chemistry and biology more. Buy $100,000 of Apple stock in 1997 and hold onto it for the next 25 years.

Gomes: I would tell him to work hard at the business but work harder to keep your friends even closer. You just can’t get that time back.

Summers: There is no younger version of me smart enough to listen to any advice a time-traveling version of me might give. I’m just getting to the point where I might believe future me. Because all of the past decade is pretty unreal.

Braxton: I would tell the younger me to make sure you start slow and that you research everything. Every nuance of what’s happening in the industry. And don’t be afraid. When I started, I was afraid, but now that I have my own facility, I’m not afraid to do anything because I know I can attract customers.

Fox: Trust you and only you. Your hustle has to be relentless. Never take your foot off the gas!

What challenges do you feel you still need to overcome?

Fox: The biggest challenge is finding meaningful retail partnership that will allow my brand to thrive and succeed long term.

Buckley: Finding funding to open a world-class craft distillery has continually been elusive.

Summers: Making the entire industry more equitable for underserved communities and disenfranchised groups. That includes equity and who gets funded, inclusion and who is empowered on the C-Suite level to make policy decisions, and how we can best serve our customers by ensuring the least protected of us are given opportunities to rise.

What do you wish you knew when you first started in the world of distilling?

Buckley: How hard it would be to raise money.

Gomes: Three things immediately come to mind: One, that the world of distilling is about sales and marketing. Invest a significant amount in that area, then invest more! Two, that my distributor was not only going to work for me, that my micro-distillery brand was too small, undercapitalized, and unable to compete in the distribution space. The big guys just eat us up. The majority of your revenue generation will be in your tasting room and home state. And three, someday I would make hand sanitizer.

Fox: Whiskey is a serious business and one of the most competitive and capital-intensive businesses I have ever owned, I knew all that going in. But the one thing I forgot to put in my business plan was time for my family. I’m still a husband and a father. That has to be part of your business plan as well.

Braxton: How much money it costs, because you are always spending money on something. I think if I knew how much money it would cost at the time, it might have discouraged me. But it has been rewarding because then we have something for my children, so in hindsight, I’m glad I did it.

Summers: A DSP is truly just a license to legally bottle and label alcohol. It’s permission by the government to “make alcoholic products” and have the government collect taxes on such. Actual distilling, which requires both hard labor and a fair amount of scientific expertise, is optional.

Looking into the future of distilling, what changes would you like to see come about?

Buckley: I would love to see more inclusion in the industry. It has gotten better over the past decade, yet still has a long way to go in bringing in people from various nontraditional backgrounds. And I would like to see more funding opportunities for those trailblazers entering the craft spirits industry.

Summers: The definition of diversity should include not just race but sex, ethnicity, sexual preference, religious affiliation, able-bodiedness, nationality, and age, among other things. Diversity isn’t just black and white.

Fox: It is such a great honor to be a distiller and distillery owner. I want to see more people of color who have earned their way in this business be respected and treated as equal to their white counterparts. I want us to share that place in distilling history so that our daughters and sons can talk about the contributions that we have made.

Braxton: I’d like to see more minorities, women, and Latinas all getting into the distilling industry. I don’t want it to be a lost art. I don’t want to lose what we’ve gained. It’s a fine skill and a craft. I’d like to see more of us getting into the craft and owning distilleries, of course.

Montana: Fawn Weaver made a comment that has stuck with me. She said there’s never been a Black-owned distillery handed from one Black family down to another generation of that family and they can trace that lineage back. It’s never happened in the Black community. And as she was saying that, we were having this call and I was a hot mess because it was right after the fires [Author’s note – Du Nord’s production facility suffered a fire in 2020 during the George Floyd protests in Minneapolis] and everything, and she was like, “You have to survive. You have to stick around because we can’t lose this opportunity for that distillery to be handed down.” And I look at my crazy-ass kids and I’m like, man, these guys are going to run this? But yeah, it would be nice.