Introduction

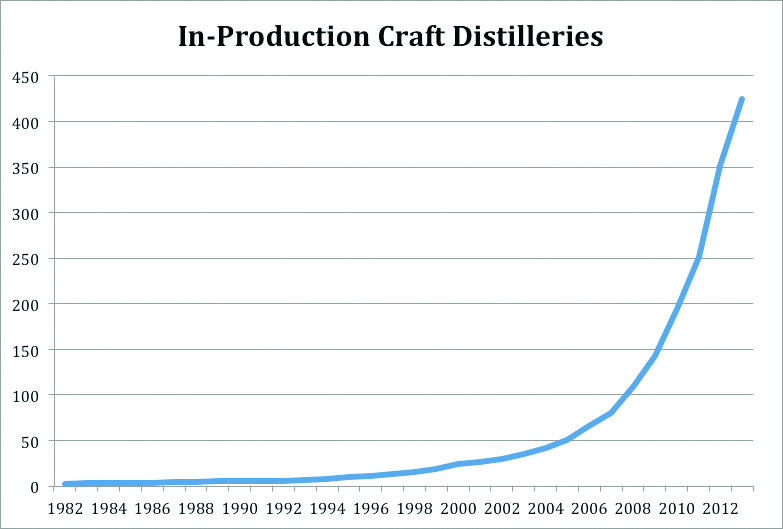

The US Craft Distilling market continued to grow and mature through last year. We identified 425 producing craft distilleries at year’s-end 2013, including 74 new entrants. The market continues to grow along the same trajectory as the Craft Brewing market, and perhaps even faster, doubling every 3 years with regularity.

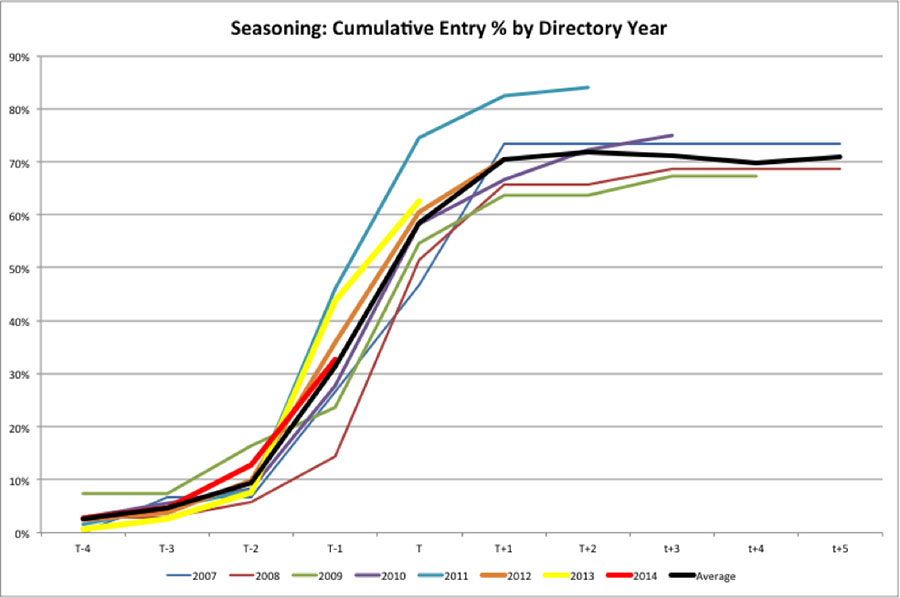

Another way to track the growth of the market is to look at the entry rates of newly listed firms in the annual ADI Directories. In each year’s listings there are some firms already producing and other prospective entrants who have not yet fully committed to starting production. Some of these “pre-producers” are licensed, equipped, and almost producing; others are nothing more than dreamers who may never get farther than their “under construction” listing.

Each ADI Directory has a one-year lag; that is, the directory published in 2014 is as-of 2013; 2013 Directory is as-of 2012, etc. As Chart 2 shows, the percentage of directory-listed firms entering the market over time is remarkably consistent. We can be reasonably confident that 75 or more of the 2012, 2013 and 2014 directories’ listings not in the market as of 2013 are already “waiting in the wings.”

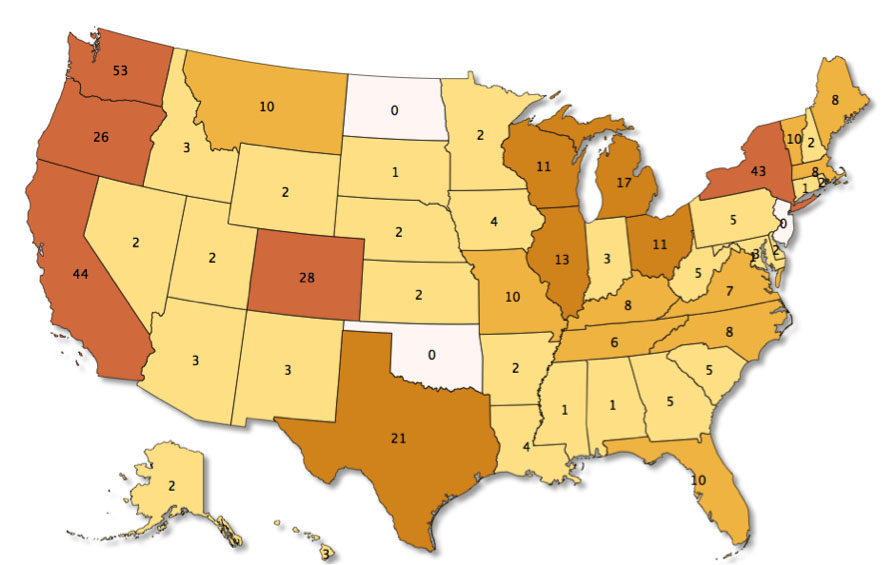

Craft Distilleries By State

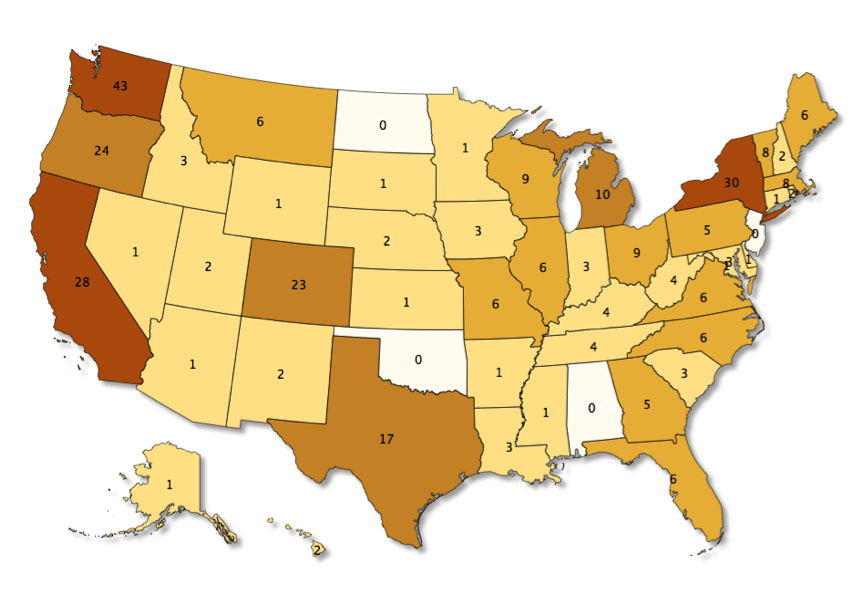

Craft Distilleries By State

California, New York and Washington State recorded the most new craft distilleries with 11, 9 and 8 new entrants, respectively. These three states continue to lead the way with 140 craft distilleries between them, fully a third of the nation’s total of 425 (see Chart 3a).

Comparing the map to last year (Chart 3b), however, reveals the growth across the country, with solid increases in the Midwest (Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin) and South (Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, Florida, North Carolina). Alabama was added to the states with an operating craft distillery, and it looks like it won’t be long before Oklahoma, New Jersey, and North Dakota end their holdout.

Craft Distilleries by Product Type

As was noted in the original full white paper, the new craft distilleries are making a wide variety of products. Many start with traditional “white spirits” (vodka and gin), while also making whiskey for aging. Vodka remains a popular category, with roughly 50% of new entrants offering one. Rum has been fairly consistently a product-of-choice for about 25% of new entrants, and, likewise, gin has remained in the 30% range.

The largest shifts have come in the whiskey and “other” categories, this last encompassing brandies, cordials, agave spirits (“tequila”), aquavit, eaux de vie, arak, and other unique spirits. The 2007-and-prior entrants were much more likely to be farm wineries than more recent entrants, which tend to be “from scratch” start-ups. This accounts for a large part of the decline in the “other” spirits category. The rise in “whiskey” is part of the resurgence in brown spirits that has been going on for some time with the “Mad Men” influence on the millennial generation and the emergence of classic cocktail culture. American whiskey has started to have its “single malt” moment.

Table 1: Product Offerings by Entry Year

|

Entry Year |

Total |

Vodka |

Gin |

Whiskey |

Rum |

Other |

|

<2005 |

51 |

51% |

39% |

47% |

24% |

63% |

|

2006-7 |

29 |

48% |

31% |

38% |

24% |

69% |

|

2008-9 |

63 |

56% |

32% |

41% |

29% |

44% |

|

2010-11 |

109 |

44% |

25% |

52% |

20% |

41% |

|

2012-13 |

173 |

49% |

36% |

64% |

28% |

36% |

“White whiskey” has also been a phenomenon of note. Craft distillers have been leading the market in reintroducing un-aged whiskies to the drinking public. Moonshine, long the alternating subject of scorn or reverence, has always been associated with backwoods illegal distilling, and, indeed, several distilleries in the Appalachian South are capitalizing on this association. Others have introduced new “white whiskey” products either to generate initial revenue while aging stock waits, or to bring genuinely interesting white spirit vodka/gin alternatives to market. The major manufacturers have definitely taken notice, and one can now find Jack Daniels’ Unaged Rye, Jim Beam “White Ghost,” and Buffalo Trace White Dog alongside the many craft distilled un-aged whisky product offerings.

Comparison with Craft Brewers

The following chart overlays the number of each type, microbrewers and craft distillers, from the “founding event” of each industry. For the microbrewers, Anchor Steam, (re-) founded in 1961, is deemed to be the “founding event,” and for the craft distillers, the 1982 entry of Jepson Vineyards and Germain-Robin.

The number of breweries in the US is near an all-time high, and micro-brew beer continues to take market share from the large brands. After a modest dip in the mid-00’s, the number of microbreweries itself has grown by over 1,000, or 80% in the past 5 years.

That kind of growth makes the numbers in the craft-distilling market seem like the stuff of hyperbole or fairy dust: 290% growth in 5 years. (In 2008 the number of craft distillers in the US was 109. In 2013 it now stands at 425. [425-109)/109 = 290% growth].) And the microbrew market was showing similar numbers at the same phase of its development. The craft distillery market continues to double every three years, and, should current growth rates continue, the number of craft distilleries in the US will be over 1,000 within 5 years.

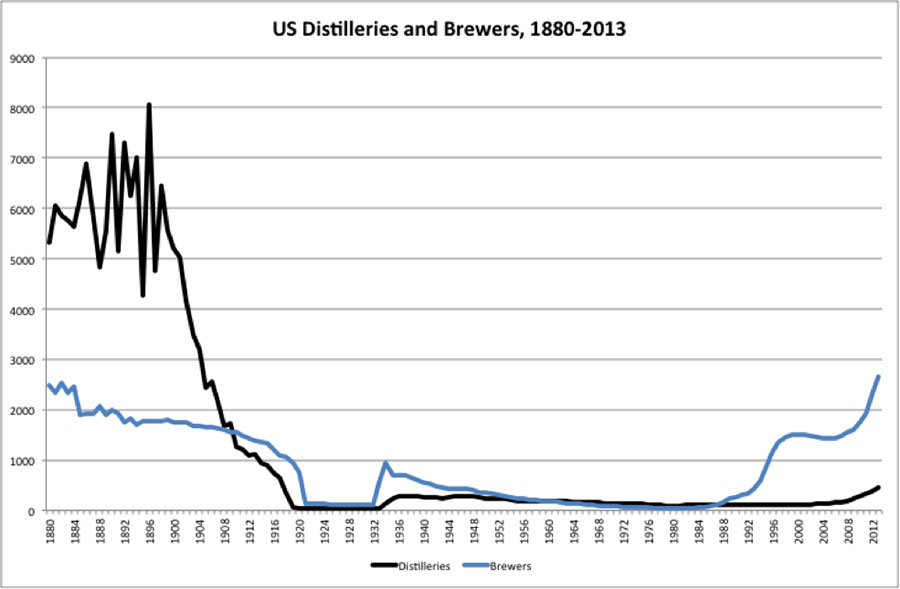

Brewers and Distillers Pre- and Post-Prohibition

In the late 19th Century, before the rise of national marketing and mass brands, small breweries and distilleries flourished across America. Although Prohibition certainly stands out as a defining event in the development of these industries, the consolidating trend was well underway before Prohibition, and continued after it.

As was true across a range of industries, the spread of mass marketing, national transportation networks, industrialization and urbanization drove consolidation. Thus, smaller producers were being marginalized and saw their numbers shrinking even well before Prohibition virtually destroyed these markets in the US.

The revival of the US brewing industry has been remarkable. Until very recently, the peak number of brewers occurred in the 1870s at around 2,500 (see Chart 5: US Brewers 1800–2013). That number collapsed to fewer than 50 in the early 1980s, and now, scarcely 30 years later, again stands at nearly an all-time high.

The explosion in new brewers over the past 30 years mirrored what took place from 1840–1870. The significant difference is that in the mid-19th Century, it was Irish and German immigration driving explosive growth in demand. The recent profusion has taken place in an essentially mature end-market driven by changes in consumption habits with consumers seeking out novel and more flavorful beers as opposed to the traditional US lagers of the “Big 3.”

The removal of Prohibition-era barriers to entry and distribution have helped enable this “age of mass specialization” in the beer industry. Craft brewers now account for nearly 10% of the US beer market, and they continue to take market share away from mass producers. Although it remains to be seen how many brewers the country will support in the future, even if the market corrects it seems highly unlikely we’ll go back to the highly consolidated industry of 30 years ago.

Similarly, there were several thousand distilleries in operation in the late-19th Century, over half of them very small, likely farm-based, “fruit” distilleries making brandy. Most of the rest were grain distilleries making whiskeys of various kinds, and thousands were small-scale producers who did not survive consolidation and Prohibition.

Prior to WWI, there were still over 1,000 distilleries in the US. And even immediately after Prohibition there were several hundred, a number that would decline to fewer than 100 in the early 1980s, when the US craft-distillery market was in its infancy.

Prior to WWI, there were still over 1,000 distilleries in the US. And even immediately after Prohibition there were several hundred, a number that would decline to fewer than 100 in the early 1980s, when the US craft-distillery market was in its infancy.

Just like the craft brewers before them, US craft distillers are both creating and fulfilling demand for alternatives to the mass-produced brands. Consumers are seeking products with more flavor and producers with stronger connections to local sources and communities. These same trends drove the craft beer market and now prevail in the US distilled spirits market, with a new generation of more knowledgeable consumers leading the way.

Although it seems highly unlikely that we’ll see a return to previous peaks, as we did in beer, the trajectory for the US distilled spirits industry is heading clearly and inexorably in one direction: up.