Brian Facquet will never forget watching his best friend wander off into the night.

It was a fall evening in 2016. His friend, also named Brian, was with him at a gathering on a boat in the marina at Annapolis, Maryland. Enjoying the reunion, Facquet was a long way from his distillery, a gin and bourbon making haven situated in a 90-year-old brick fire station in New York’s Catskill Mountains. At the time, it was called Prohibition Distillery. It was Facquet’s friend Brian who would unknowingly steer the business in a new direction and a new name.

Brian’s full name is never mentioned when the story of the distillery is told, since he was a Navy SEAL working for the C.I.A. in Afghanistan. What Facquet shares with fans is that Brian’s loyalty, personal values, and sense of purpose were sources of constant inspiration. The two shared a trailblazing mentality, too. In Facquet’s case, he opened one of the very first modern distilleries in the state of New York. Secret operations would cause Brian to vanish for long spells, but he still managed to follow his buddy’s progress in making spirit-lovers smile.

Standing on the boat that night, Brian lifted a whiskey bottle as he gave a speech about Facquet for the gathering. It ended with a toast to the distiller, telling him to “do good.” Facquet, a naval veteran, lifted his bottle in return as Brian strolled down the dock and drifted away under the stars.

He never saw Brian again.

“He ended up dying in Afghanistan about a month later,” Facquet recalls. “‘Do good’ were actually the last words he said to me. They really resonate… On the anniversary of his death in 2020, we just wrote the name “Do Good” on the side of the building. It forever changed the name of my distillery, because those words haunt me as much as they motivate me.”

Facquet says Brian’s example is partly why he is trying to help fellow distillers who are truly struggling. He’s currently president of the New York State Distillers Guild, a position that gave him a front row seat for how craft operators temporarily gained permission to do direct-to-consumer (DTC) sales and shipping in the early weeks of the pandemic. Many small distilleries altered their business models overnight and made big investments in their online stores. New York’s DTC experiment went on for 15 months. Facquet heard from numerous guild members that DTC was a solid source of revenue. Then, in June of 2021, New York’s governor at the time, Andrew Cuomo, abruptly ended the state of emergency — and the distillers’ DTC abilities — with no warning.

Since then, Facquet and the Guild have been leading the charge to bring it back.

But a number of industries and special interest groups in the Empire State are flexing their political muscle to fight that. “DTC challenges the three-tiered system at its heart,” Facquet points out, “which is the big, long-established legalization of a monopoly, which is getting worse and worse.”

Getting worse, in the view of small distillers, because of how much corporate consolidation has occurred in alcohol distribution. In 2016, the Federal Trade Commission allowed Southern Wine and Spirits to merge with Glazer’s, which turned the nation’s first and fourth-largest spirits distributors into one mega-company. Then, in 2019, Republic National Distribution Company merged with Young’s Market Co. That FTC-approved move combined the nation’s second-largest spirits distributor with the one that had replaced Glazer’s as the fourth largest. The trend has only continued. Last year, Southern-Glazer acquired Epic Wine & Spirits, a premium spirits distributor in California, one of the largest liquor markets in the nation.

Cris Steller, executive director of the California Artisanal Distillers Guild, notes that spirit producers in his state also had temporary DTC during the pandemic — and also faced real financial consequences when they lost it. Steller says these hurdles should be viewed through the broader context of distributors merging, which has left fewer distributor catalogs for craft distilleries to get spots in, not to mention fewer overall options when trying to get picked up.

“When you look across the country, you can see all the deals that have come together,” Steller observes. “If there used to be five catalogs, now there’s three catalogs — and the catalogs don’t get thicker. So, getting into that book is impossible now. It’s why the distributors have been dropping small brands.”

California distilleries are also fighting to get DTC back permanently. Leading the battle from opposite shores, Steller and Facquet agree that DTC is a powerful tool for small businesses to create their own distribution strategies while trying to weather the fallout from three years of economic upheaval.

For the owner of Do Good Distillery, the stakes couldn’t be higher.

“It’s the limitation to access on our markets that’s hurting everyone,” Facquet stresses. “There are distilleries slowly going out of business in New York as we speak.”

Pennsylvania Freedom

Anchored in a warehouse in the industrial part of Pittsburgh’s Strip District, Maggie’s Farm Rum made a name for itself as one of the first dedicated rum distilleries in the United States.

Nine years later, the business keeps getting more profitable, spurring plans for a move into a larger facility in the near future. Maggie’s Farm co-founder Tim Russell says the fact that Pennsylvania distilleries have permanent DTC played a big role in his success story. Spirit makers in his state have no limit on how many bottles or cocktails they can sell directly to customers, outside of common-sense safety in the case of mixed drinks. It’s a business-friendly environment that’s allowed Maggie’s Farm Rum to enjoy its trajectory without turning to multiple investors.

“We opened our doors with less than $100,000, which never would have been possible without DTC in Pennsylvania,” Russell admits. “Without any capital infusion, year after year, we’ve been able to grow the business just by direct sales.”

In addition to DTC’s typical benefits, it became a kind of mega-bomb of profitability for Pennsylvania distillers in early 2020 after authorities there temporarily closed all of their state-run liquor stores and didn’t offer curbside pickup for weeks. Suddenly, small operations like Maggie’s Farm Rum were the only place stressed-out people could buy any spirits to have at home. Russell recalls eventually running out of all his products.

“If there was a Bacardi’s drinker, then they had no access to buy rum except to come to a business like ours,” he remembers. “We were delivering eight hours a day.”

Russell is careful not to over-romanticize those early days of the pandemic, but he does acknowledge they are an interesting window through which to study DTC.

“It’s just amazing that we’ve been able to grow without getting into some crazy amount of debt,” he says.

Erik Wolfe, co-founder of Pennsylvania’s Stoll and Wolfe Distillery in Lancaster County, also experienced a similar sales boom when the doors on the state liquor stores were chained up. That anomaly in 2020 introduced Wolfe’s products to new customers, many of whom came back for more, though he notes that Pennsylvania’s legal framework for distilleries producing under 100,000 gallons annually has big perks year-round.

“DTC is phenomenal for us,” Wolfe acknowledges. “To have the chance to develop that direct-to-consumer channel means you can build a relationship with a consumer… For us, as a small producer, sometimes with a distributor we’re faced with either being a very small fish in a very large pond or being a large fish in a small pond. With direct-to-consumer, I also don’t have to worry about whether or not my messaging is being repeated in an accurate way. When it comes to messaging, we’re speaking directly to the customers.”

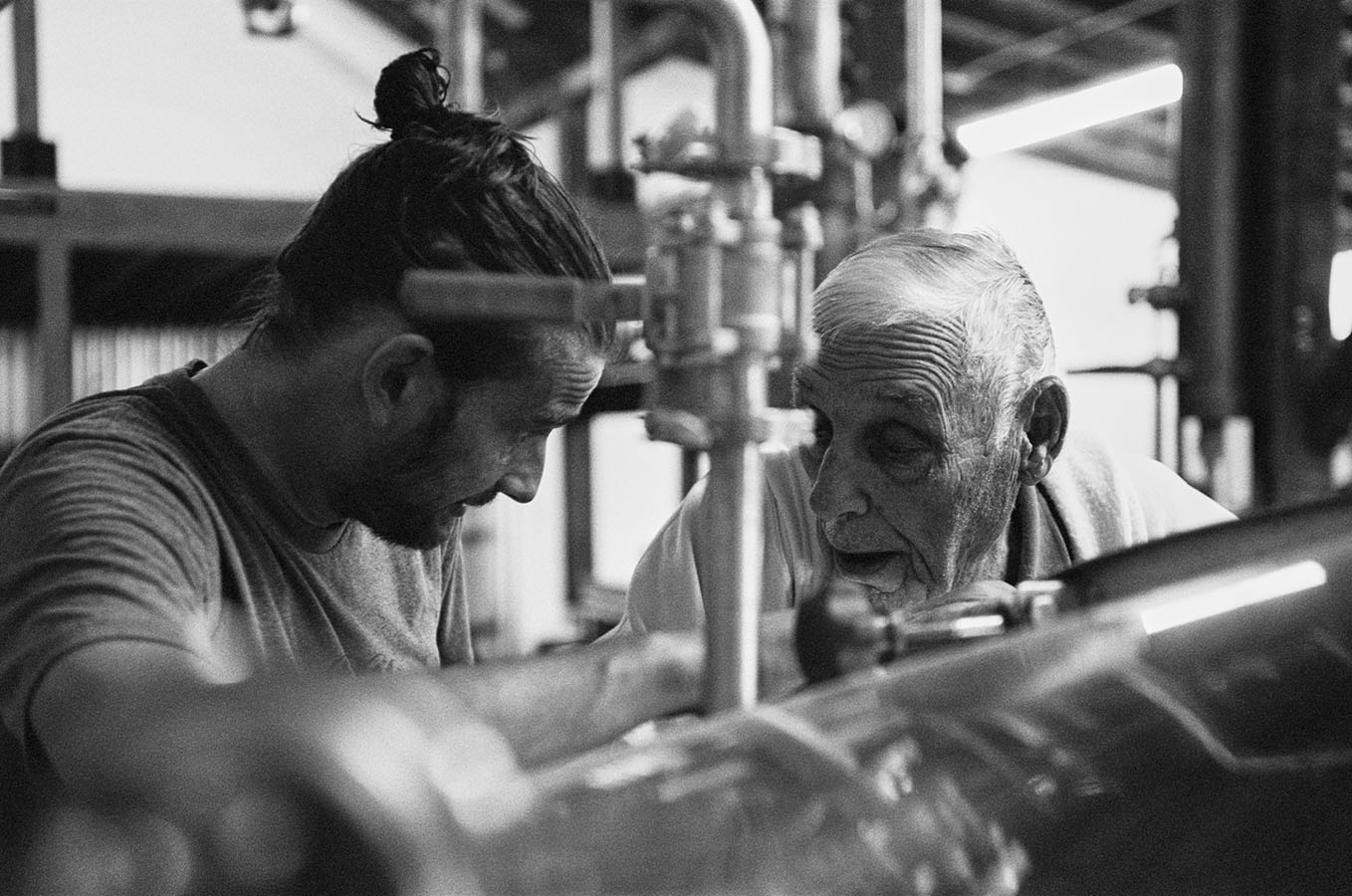

(Michelle Gustafson for The New York Times)

For Stoll and Wolfe, the messaging really matters. Wolfe was born and raised in Lancaster County; his ancestors were deeded their farm by the brother of Pennsylvania’s founder, William Penn. When Wolfe and his wife Avianna decided he’d be leaving his marketing career in New York to move home, it didn’t just mean their daughter would be the fifth generation of the family to attend the same elementary school; it also meant that their upstart distillery would represent the history of America’s pioneering frontier distillers. Wolfe wants customers to know that the Pennsylvania-style rye whiskey he and his late partner Dick Stoll formulated, using 30% corn as a counterpoint to the rye’s spiciness, is an homage to some of the nation’s first farmers to engage in year-round distilling.

As a marketing expert, Wolfe isn’t confident that a distributor’s sales representative would try hard to convey the fact that his distillery is ten miles away from where the National Register of Historic Places recognizes as the birthplace of American Whiskey. DTC allows Wolfe and his team to handle the educational aspects themselves, either inside their tasting room or at big cultural events like the Philadelphia German Society’s Christmas Market.

“We’re a hand-sell — no one is going to see our Super Bowl ad,” Wolfe chuckles. “But when we can tell someone why the whiskey tastes the way it does and the ethos behind the brand, it’s incredibly compelling and a lot of folks discover us. So, DTC has been a godsend.”

Wolfe’s friend and fellow distiller in Lancaster County, Nate Boring, has talked to Distiller before about the lines of cars that went around the block to get bottles from his operation inside the Zoetropolis Theatre when COVID started. Boring thinks this unexpected windfall was the main reason his theater, bar, and restaurant — and his spirits brand, Lancaster Distilleries — survived the lockdowns. That alone was enough to make him a believer in DTC. As Boring continued to run the business, he became convinced that embracing DTC instead of traditional distribution equals holding on to profits.

“My experience is that there is no better thing to help a small business than direct to consumer because you get to cut out the margin the distributor is taking and you hold onto it,” Boring explains. “I mean, that’s huge — it’s kind of everything.”

Saving that margin allowed Boring to purchase delivery vehicles, which he has in turn used to make DTC home deliveries a vital part of his business. He knows that distillers in New York, California, and other states are battling to get the same market liberties that he, Wolfe, and Russell enjoy — and he’s rooting from a distance.

“If all the states were able to adopt it, it would be great for the industry, especially small players,” Boring says. “In terms of DTC mitigating challenges with distribution, that’s a hundred percent true. If I was in a three-tier state, my business model would look a lot different.”

The Coming Push

So, how did Pennsylvania get so far ahead of the curve on DTC?

“I think it just came down to arguments against the state-run liquor stores and the push for privatization,” Russell offers. “There had been a stalemate over the years, so eventually there was a compromise for keeping the state-run system, but it included adding a lot of other aspects to alcohol sales. Craft distilleries really benefited from the idea of opening the door to other things.”

New York does not have state-controlled liquor stores, but it does have its own legal quirks around alcohol sales: The state will only allow major national chains to have a single location within the state (Total Wine has been in a three-year legal clash with regulators on this front). Facquet says this — among other factors — appears to have caused concern in the state’s retail sector about bringing DTC to New York distilleries.

As New York guild members contemplate the next attempt at a DTC bill, they have been holding talks with the state’s breweries and cider producers about potentially creating a united front.

At the start of 2022, California distilleries introduced a state senate bill, SB620, to get permanent DTC. It eventually died in committee. Steller, who was part of advocating for the bill, says a specific special interest group managed to stop it. However, Steller and his guild members kept arguing their cause. At the start of October, they convinced California Governor Gavin Newsom to sign Assembly Bill 920, which brought back temporary DTC for California distillers until the end of 2023.

“It was an emergency bill, so it started immediately when he signed it,” Steller emphasizes. “We’re going to go back soon to work on a permanent bill again. I don’t know what it’s going to look like, because what we want, and we need — and what the legislature thinks is best — are just very different than what the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States and the wholesalers want.”

He adds, “We got to where we can survive another year, but we know the big money will be rolling back at us.”