Excerpt from Whiskey Business: How Small-Batch Distillers Are Transforming American Spirits

Craft spirits was just toddling forth when an Oregon lawyer-turned-businessman approached the owner of America’s only eaux de vie distillery. The rest became our history.

The late 1970s had been a lean time for the orchards that Steve McCarthy’s family owned in northern Oregon’s Hood River Valley. His great‑grandfather and grandfather had cultivated the primarily apple and pear orchards at the turn of the twentieth century and then lost them in the Great Depression. McCarthy’s father went into the more lucrative timber industry after World War II and rode a national building boom to affluence.

The money allowed the elder McCarthy to buy up the orchards again, and they served for years as a staple of the family’s income, along with other ventures. Then, through either poor crop quality or poor market conditions (it’s not clear which), the family found itself unable to sell all the apples, pears, etc., that their orchards produced. One year the packaging firm that the family contracted with for distribution sent invoices rather than a check. Fellow Oregon orchardists were being wiped out.

Something had to be done.

The younger McCarthy at this point was in his late thirties. He had graduated from Reed College in Portland, three hours north of his hometown of Roseburg, and earned a law degree from New York University. He had worked in the public sector, including as general manager of the Portland region’s transit system. As the 1980s started, he was practicing law and running a family‑owned company that manufactured hunting and shooting accessories.

McCarthy himself was an avid outdoorsman. He could as a teenager, in his own estimation, “hike the legs off anyone in the State of Oregon.” As a 20‑year‑old, he embarked with two friends on a more than 18,000‑foot climb in the Nepalese Himalayas; one friend died from a fall just as the trio reached their goal. (McCarthy later sold a story of this triumph‑turned‑tragedy to Sports Illustrated while a law student in Manhattan.)

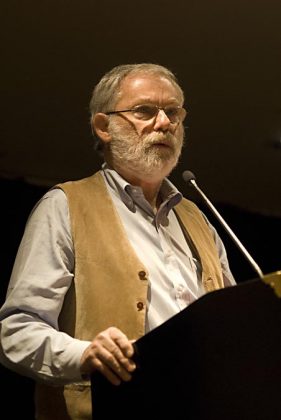

McCarthy’s travels also took him to western Europe, including to the southeastern French city of Grenoble for six months during college in 1960. It was there that he first encountered eau de vie. When the family orchard started having trouble in the late 1970s, the bearded, bespectacled McCarthy realized that distilled fruit juice might be the answer, an opportunity, he thought, to make “an elegant, expensive product” for sale in America—in North America—where there were no eau‑de‑vie distilleries.

Even imported eau de vie was difficult to find, McCarthy discovered, mostly the provenance of upscale restaurants in major cities such as Seattle and San Francisco. Moreover, McCarthy also realized that the Bartlett pears his family had been growing off and on for nearly a century were one and the same with the Williams pears that undergirded the eau de vie de poire he had discovered in France.

“It’s just so logical,” McCarthy thought. Besides, turning it into alluringly tasty alcohol “has to be the greatest way to sell fruit.”

In the summer of 1983, McCarthy decamped for France to research his idea. He returned in the fall and heard through the winemaking industry grapevine that a former academic and violinist from West Germany named Jörg Rupf was now making eau de vie in tiny amounts in Emeryville, California. McCarthy quickly tracked Rupf down. He was the one man on the continent who might be able to help him realize his plans.

There was just one hitch.

“Look, I’m going to go out and compete with you,” he told Rupf. “But, to be fair, I should pay you. Why don’t I pay you $75,000, and you teach me how to do seven or eight products?”

Rupf agreed. It was the first meeting of the minds in the American small‑batch spirits movement, a watershed of information sharing.

McCarthy’s planning continued through 1984 and into 1985. He bought a small warehouse on the western bank of the Willamette River in downtown Portland. He got the necessary federal license, and he named the new operation Clear Creek, after the family orchard. He ordered a pot still from West Germany. It broke in transit, and the insurance company took it off his hands. A second one arrived, and Rupf came up from California.

McCarthy proved an apt pupil, and, in the fall of 1985, they made a batch of poire that surprised McCarthy with its quality. He figured he had the right equipment, good fruit and unique expertise in Rupf, yet he had not expected the first run to turn out so well. There would be some iffy goes of it in the future, but this inaugural poire came off without a hitch. Selling it and subsequent early batches was another matter.

Luckily, McCarthy could not have picked a better city or a more promising state to commence the first small‑batch commercial distillery outside of California or Kentucky.

Portland itself was by 1985 an epicenter of America’s burgeoning craft-beer movement. The city of just under 500,000 hosted two craft breweries, Widmer Brothers and BridgePort, both of which operated in the same gritty industrial area as McCarthy’s Clear Creek. Cartwright Portland on SE Main Street, the first craft brewery in the entire Pacific Northwest, had already come and gone by 1985, its mild English‑style ale, though of inconsistent quality, apparently enough to pique interest.

Finally, Fred Eckhardt, a handle‑bar‑mustache‑curating ex‑Marine and professional photographer, started writing the first regular beer criticism column in a major American newspaper, the Oregonian, in April 1984. And in 1976, Don Younger, a long‑haired corporate marketing refugee, created what became perhaps the most influential beer bar west of the Mississippi in his Horse Brass Pub on Belmont Street, which specialized in being the first to serve many craft-beer brands.

Although far from spirits technically, Portland’s craft-beer scene unmistakably fostered a culture of appreciation for small‑batch alcohol made with traditional ingredients by independent producers, such as Steve McCarthy.

Closer to spirits’ technical wheelhouse, the wine industry surrounding Portland was undergoing its own explosive growth. It had all started in 1961 when San Francisco native Richard Sommer, a trained horticulturalist and army veteran, started the first winery in Oregon since Prohibition to make wines primarily from higher‑end European varietals, including Pinot Noir, a notoriously finicky grape that winemakers farther south in California were having particular trouble with.

Sommer’s first Pinot Noir batch in 1967 proved exceptional, and the Oregon fine wine industry was on its way to becoming the nation’s fourth‑largest, after California, Washington, and New York. Several producers, including Sommer’s HillCrest, formed a wine‑promoting trade group in 1969, and the Oregon Wine Festival launched the same year. All the while, James Beard, at the time the nation’s leading food writer and a proud Oregon native, talked up his state’s winemaking potential to various audiences.

McCarthy was well aware of Oregon’s fine wine success and Portland’s craft-beer growth. The state’s reputation for fine wine by the 1980s helped him at least get meetings with higher‑end restaurateurs and retailers, particularly in his old stomping grounds of New York City.

Overall, though, McCarthy encountered the same arctic indifference other early small‑batch spirits pioneers did. Most merchants just did not know what to make of an eau de vie from the Hood River Valley. Like Jörg Rupf, who also became an early investor in Clear Creek, McCarthy understood from the beginning that his market was infinitesimal against those for the likes of vodka and rum, never mind Chardonnay or light beer.

“Producing wonderful eau de vie,” as one critic noted, “is a little like being the greatest bouzouki player in America: Regardless of your virtuosity, your audience will be small.”

Consequently, McCarthy never figured that his small‑batch distillery would amount to anything similar to the promising reputations that some of the state’s wineries and breweries enjoyed. For years, then, he operated alone—literally as Clear Creek’s sole worker after Rupf helped on those first batches and as the only such distillery outside of California at that point.

McCarthy produced 60 20-bottle cases that first year, and production would remain under 1,000 cases annually for the rest of the decade. By 1990, he was grossing perhaps $100,000 in sales. His family’s other business concerns provided McCarthy his income, not spirits. (He sold the hunting and shooting supply company in 1987, for instance.)

Even after he added a second still and moved to a bigger warehouse in 1991, production did not creep much beyond perhaps 1,000 cases annually. Distribution remained almost entirely in Oregon. The odd bottle of Clear Creek Poire might turn up in New York City for $22 a pop, but otherwise the distillation remained more a labor of love, a personal and commercial curiosity in a late 1980s spirits landscape that trended as far from independent and small‑batch as it seemed possible to get.

The relentless decline in Americans’ spirits drinking—by 1984, per‑capita consumption had declined five straight years and retail sales three—forced the industry’s biggest players to both diversify their offerings and gobble up their competition. A dog‑eat‑dog ethos prevailed during this bear market for spirits as even gigantic concerns such as Seagram and Heublein struggled to maintain shares of a dwindling market.

Rather than propping up flagging whiskey brands, Seagram test‑marketed a no‑alcohol wine and leaned more heavily on an existing lower‑alcohol wine line. Heublein, too, looked more to wine than spirits for its bottom line, test‑marketing a carbonated white wine soda and launching marketing campaigns to remind people that brands such as Smirnoff were better with cocktails than on their own.

Other, smaller firms went the wine‑cooler route, jumping on a juggernaut that already accounted for one in 10 U.S. wine sales after only a few short years. Heublein even had a lower‑alcohol vodka, the approximately 40‑proof Popov brand, introduced at the turn of the decade and quickly proving a smash hit as the second‑top‑selling vodka behind Smirnoff.

If such gimmickry did not appear to be working, there was always the tried-and-true approach of hiring Wall Street advisers to hunt for acquisitions. The spirits industry from almost the first days after Prohibition had always had its conglomerates, its large companies whose holdings might include a variety of foodstuff brands well beyond whiskey, vodka, etc. Heublein controlled Kentucky Fried Chicken, for instance, and Seagram and its new president in 1984, Edgar Bronfman Jr., were famously involved in movie and theater production.

In the early 1980s, the sizes of these conglomerates grew, as did the number of new players. Guinness, the Dublin‑based concern most famous for its signature dark beer, went on an acquisition spree in the mid‑1980s that perfectly illustrated the often head‑spinning brands within brands within brands approach that became the norm of an alcoholic beverage alcohol industry searching for steady profitability in a choppy market.

Guinness partnered with Moët Hennessy, an importer and distributor that had itself recently acquired another importer and distributor, Schieffelin & Company, whose portfolio included brands such as Johnnie Walker blended whiskey and Tanqueray gin. Guinness around the same time purchased importer Schenley, one‑time owner of the famed George T. Stagg distillery in Frankfort, Kentucky, as well as several other spirits producers. Finally, Guinness also partnered with Bacardí on the rum giant’s operations in Spain, bringing yet another spirits brand under its corporate umbrella, where they operated alongside beer and wine.

As for Heublein, Grand Metropolitan, a real estate company based in the United Kingdom, acquired it and its nearly 100 labels in January 1987, after having just partnered with Martell, one of the Big Four Cognac makers, on an international distribution network. And Seagram set about in 1985 simply splitting its many spirits tentacles into four companies, two of them new, under the same corporate cloud.

“The industry has been in trouble for five years,” noted Marvin Shanken, an ex–real estate investment banker turned publisher of alcohol‑industry trade publications such as Wine Spectator. “Seagram is the first to bite the bullet and reorganize the company to meet the problems they face.”

If these problems, particularly the sharp drop in spirits consumption and the rocket‑ship rise of fine wine styles such as Chardonnay, were nagging enough to rattle even hegemons such as Seagram, what hope had infinitesimally smaller operations such as Jörg Rupf’s St. George and Steve McCarthy’s Clear Creek?

There were no more than five small‑batch, or craft, distilleries in the United States by 1985—all of them were in California and Oregon. The notion of small‑batch spirits, however, if not yet in the lexicon, was much more widely felt.

Larger, seemingly disparate trends such as the rise of single malt, barrel‑strength, and single‑barrel whiskeys in the early 1980s; the introduction of Absolut vodka the decade before; and the rapid ascent of fine wine and even craft beer in places were setting the stage for small-batch spirits. These strange bedfellows were creating a context for consumers to understand what Steve McCarthy and Jörg Rupf were getting at.

That there could be a small-batch, or craft, spirits movement in America was no more improbable, really, than the fact that in 1985 the number of craft breweries nationwide was about to crest 20 after an identical number of years trying. Or that American fine wine increasingly dictated the tastes and textures of even ancient European styles.

The travails of the wider spirits industry might even prove a boon. Almost a generation before Steve McCarthy met Jörg Rupf, Bill Samuels Sr. had resurrected his family’s bourbon fortune in the form of a Loretto, Kentucky, operation called Maker’s Mark.

Beginning in the early 1950s, Maker’s Mark made small batches of the classic American whiskey in traditional ways with traditional ingredients. It never had the marketing reach of much larger competitors, but a funny thing happened: Maker’s Mark grew and grew as the wider bourbon sector collapsed throughout the 1970s.

Maker’s Mark was not independently owned by 1985, but its stonking success—a front-page Wall Street Journal article five years before had told the world “Maker’s Mark Goes Against the Grain to Make Its Mark”—clearly illuminated the demand that was out there in America for better-tasting spirits whatever the wider marketplace.

Could new suppliers such as Rupf and McCarthy capitalize on that demand? The answer was coming faster than anyone could’ve realized when the two first met.