Strip away the ads of lush green fields and the well-lit exterior shots, and a simple truth remains: Making spirits is an industrial process. It doesn’t have to be pretty. Some great spirits have been created in spaces akin to your local car garage full of hoses, pipes, and random containers. At the end of the day, looks don’t matter because taste is king.

That said, reclaiming an old building for your distillery offers many advantages that can make the cost worth it. Visitor centers, tasting rooms, and event spaces are now widely considered must-haves for craft distillers, and making that space a beautiful showpiece to call your own never hurts.

Still, money is an important consideration. Even for a big player like Michter’s and their amazing Fort Nelson Distillery or midsized operations like Tenmile Distillery’s beautiful former farm turned distillery/tasting room, the costs and delays of renovating their space can make aspiring preservationists balk. Done right, however, the result can be a masterpiece that provides revenue, attracts attention, and brings your fans back time and time again.

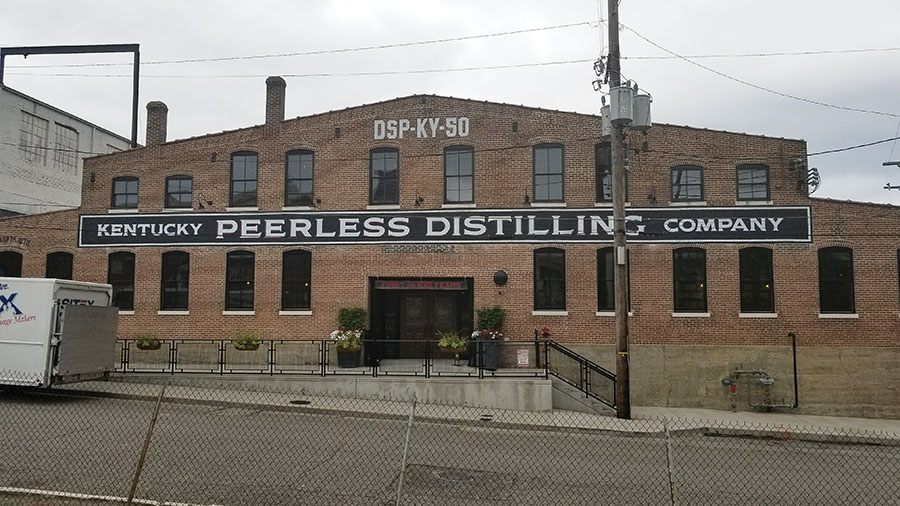

There isn’t one way to do this. In Louisville, Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co. transformed a historic downtown building from the mid-1880s into a working distillery, barrel warehouse, and visitor center. Tenmile Distillery in Wassaic, New York, renovated a rural 1920s farm into a showcase of the old and new. And New England Sweetwater Farm & Distillery in Winchester, New Hampshire, converted a 140-year-old former hardware store into a craft distillery in the heart of their town. This is what they learned from the process.

What first attracted you to the building that became your distillery?

Carson Taylor, president, Kentucky Peerless Distilling: I knew that I wanted an old building. I wanted to be in downtown Louisville because of Whiskey Row and the tourism aspect but I also knew that I needed to have space that lent itself to distilling. We would love to be on the corner of Main and Main (where East and West Main Streets meet in Louisville) but you can’t get trucks in and out, you can’t get grain, dry goods, and fill bottles in and out every day. So it had to have loading docks but still have a cool aesthetic.

I found this building on 10th and Main Street in downtown Louisville. It’s 140 years old and it was originally built as the largest tobacco warehouse in downtown Louisville. They were here for about 30 years, and then The Walker Bag Manufacturing Company (a maker of feed and burlap sacks) had this building for about 70 years, followed by a company that made wire. I got the building just about 10 years ago, and we spent two years under construction. It’s a 43,000-square foot building. It has that vintage look from the outside, but we can also get all of our trucks in here. What attracted me was the possibility of getting tourism through the building, the look and aesthetic of the building, and then us being able to cook, ferment, distill, barrel, and bottle all under one roof.

Alisa Lawrence, owner, New England Sweetwater: The original distillery location was slated for the family farm a few miles up the road. But with opposition from nearby residents who were against the idea of having a distillery in that location and a requirement where we would have to move the barn on the farm to a greater distance from the house to meet specific regulations led to having to come up with alternative locations.

After discovering a 140-year-old building situated along a historic river that flowed through the area, we were hopeful that purchasing and renovating the existing building for use as a distillery would be more cost-effective than constructing a brand-new barn and that the new location on Main Street in the heart of the town would be a significant advantage.

Joel Levangia, owner and general manager, Tenmile Distillery: John Dyson, owner and chairman of Tenmile, said he wanted “a dairy barn that isn’t falling in, near a major road.” Given that our farm is sandwiched between Route 22 and a Metro North train station that connects to Grand Central Station in New York City, the “arterial” portion of that directive was pretty well satisfied. The barn’s original construction by New York State in the 1920s included three-foot-thick concrete brick walls, and a famous architect, Allan Shope, who renovated the barn to be a winery with dramatic wood columns supporting the original rafters, hardwood floors, and commercial kitchens and bathrooms. All the building lacked was a set of lunatics who wanted to make single malt whiskey.

When you started, did you have any concept of what would go into making the building what you needed it to be?

Levangia: John Dyson had a good conceptual framework from building out three wineries and several manufacturing facilities over the course of his career. As the project manager, one of my first actions was to ask Mike McCaw, co-author of The Compleat Distiller and a retired Weyerhaeuser engineer for pulp and paper mills, to fly out and walk around with me to discuss this issue more concretely.

Taylor: Because I’ve been in construction, nothing really surprised me. But, you know, I had it laid out where our customer can walk through every aspect, I wanted everything all under one roof. So they don’t have to travel, eat, go to another building or travel outside. They can go from the family history to the cooker to the mill to the fermenters and be able to walk through the stillroom and the bottling room and actually a barrel warehouse.

What was the renovation process like?

Levangia: Once we had crystallized what needed to be done, there were three areas of focus. First was an additional “garage shell” with industrial drainage and surface coatings to deal with large amounts of moisture. Second was equipment specifications and functions and organizing them in the space plus process and cooling water considerations, and third was focusing on facility-as-marketing-tool at every turn. We wanted it to be clear to our customers that we are doing everything the right way and so we had to be sure they could see everything with their own eyes and get fully into the inner workings of the distillery with their five senses. Knowing your goals at the outset makes everything easier.

Taylor: We had to fit it in a space with 12-by-12 beams throughout the building. It’s not just a free-span building to be able to put up walls or fermenters or stills or wherever you please. It was a little bit like Tetris being able to figure out, you know, all the different rooms we needed. We had to create a tour path where we’re never in the tourists’ way and they’re not in our way.

Alisa Lawrence: The renovation of the building on Main Street took nearly two years to complete. During this process, several innovative and resourceful steps were taken to repurpose materials and salvage parts from a collapsed barn nearby. Some of the highlights of our initial renovation were our reuse of materials and what was at hand. For example, we used the original attic floor for our walls in the renovation. We salvaged the beams from the collapsed barn and used them as well. We even milled down one of those same beams to create chairs for our bar.

Parts of the barn roof were also used in the renovation project. We did as much as we could to incorporate elements from the collapsed barn into our renovation. Even the windows used in the renovated building were from the second floor of the original structure.

What was the hardest part of the renovation process?

Levangia: Timing. It is very difficult to get all the trains into the station at the same time. There is a tool called a Gantt chart used in property development and film production that can help you to know more or less where you are in your project, because once things get going you can wind up tripling your project costs as various parts of the operation sit around waiting for other parts to finish. We were able to do a good job with this because we knew it was important when we started.

Alisa Lawrence: Encountering all the usual ups and downs during major rehabilitation projects. All of the surprises, reworking our plans and designs, and environmental issues, as the building abuts the Ashuelot River.

Taylor: If there was a hard part, it would be trying to put a Class 1, Division 1, high-hazard barrel storage and the distillery right in downtown Louisville. Trying to get the zoning correct, getting high hazard classification for the rooms with fire ratings, and sprinkler systems took time to get done.

What part of the build are you most proud of?

Levangia: Harry Basil of American Curtain Wall made us a beautiful glass wall to separate the distillery production floor from our patrons. Harry had much bigger jobs going on, 30-story buildings, but we were unique and he took great care in matching his rigid aluminum framework to the curves and hollows of our wooden building. It’s remarkable if you take the time to consider it.

Alisa Lawrence: The actual distillery, the beauty of it, the functionality. It is a work of art. Being able to preserve the original architectural elements has also made us feel extremely accomplished.

Taylor: For me it’s the look and feel of the place. When a lot of these older buildings get renovated, I feel like they sometimes take a lot of the character out. They might leave a brick wall or something. I wanted to leave as much of the aesthetic — the ceiling trusses or walls or whatever it is — to really get that feel out there … my vision was to keep it so that you feel like you’re truly going back in time.

What kinds of benefits have you seen from all the time, work, and money invested in taking that historic reuse path?

Cordell Lawrence, chief operating officer, Kentucky Peerless: Reverence for the various skilled laborers who constructed the original structure, toiled within the building over its lifespan as well as the skilled laborers who breathed new life into our historic building.

Alisa Lawrence: By incorporating salvaged and recycled materials, we not only reduced the environmental impact of the renovation, but also added a unique and historic character to the Sweetwater Distillery’s location on Main Street. This approach aligns with sustainable and eco-friendly building practices while preserving elements of local history.

Levangia: It’s extremely “on-brand,” and this is true for anyone making aged spirits. When one of your major selling points is a certain amount of age in a barrel, having an old building/venue adds to the general atmosphere of staid responsibility that contributes to the comfort level with the product. Even though Tenmile Distillery is relatively new as a company, we have waited the requisite three years to release a whiskey that we ourselves made on-site, and we have produced enough to be able to have product at eight years old that is authentically produced and aged. The building supports and illustrates our commitments.

What kinds of reactions do you get from consumers?

Cordell Lawrence: Consumers feel as if they are taking a step and a sip back in time given the resurrection of both our historic Peerless brand as well as our historic building.

Alisa Lawrence: Our customers are always taken in by the design; they can tell immediately upon entering that thought and care were put into the planning and execution of the space.

Levangia: Our patrons generally think it’s a visually spectacular room and facility, and when you pair the gorgeous spaces with the beautiful surroundings, excellent cocktails, and first-rate food, you get a total package that drives a lot of repeat visits and word of mouth. This is the goal, and the job is not to bankrupt yourself on the way so that you can have a shot at building and growing a successful, sustainable business that will be a good steward of this fabulous place you’ve preserved for years to come.