For craft distilling, the story of the last 20 years borders on mythic: Creative makers, imagining a future filled with novel spirits and diverse flavors, poured their hearts and souls into startup endeavors, often maxing out loans and cashing in retirement accounts to do so. Those with the boldness to dream have reaped the rewards of their daring: blazing trails, building businesses, and establishing legacies that will follow them into the future. Even when met with challenges, these undaunted risk-takers have persevered and prevailed.

That’s the story we’ve all heard, right? That the buoyant growth of craft distilling can’t be stopped; that there’s nothing but upside to this industry.

Except that’s not the full story. Yes, the last two decades have been a boom era, as craft distilleries have proliferated nationwide — from just 75 in 2006 to 2,283 in 2022, according to The American Distilling Institute (ADI) — and sales of craft spirits continue to climb upward, enticing an American public eager to sip local, artisanal, handmade products. But the macro trend obscures less obvious events —namely, that some distilleries are not making it.

Erik Owens, president of ADI, has been tracking the nation’s Distilled Spirits Permits (DSPs) for years, noting new entrants annually. “From 2010 to 2019 is exponential growth … and there were almost no exits during this time,” he says. “Everybody was going in; it was very rare that people were coming out.”

But, he adds, “COVID-19 flatlined everything.” While the pandemic didn’t seem to stop people who already had funding and plans in motion, Owens posits that it likely held back others who weren’t as far along in the process from moving ahead. Meanwhile, distilleries that had their own still were able to hold on by making hand sanitizer, but “a lot of the little hobbyist distilleries just folded.”

And as the hand sanitizer business dried up and PPP funds were exhausted, many distilleries were left in difficult straits. Some are now facing the possibility of closure; others have already made that decision. On ADI’s forums, Owens is seeing more used equipment for sale — even whole distilleries up on the block.

Amid pride that they made it as far as they did, those who have reached the end of the line also express pain and regret. Their stories are saddening and uncomfortably ordinary. They serve as an example for everyone in the business: It could happen to any of us.

The Beginning of the Trend

For some distillers, thoughts about closing began even before the pandemic. COVID may even have delayed the inevitable, as the switch to making hand sanitizer provided a revenue stream that was often the most robust they’d ever had.

Scott Maitland, who co-founded TOPO Distillery in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, in 2012, was on the cusp of closing in March 2020 when, suddenly, his equipment was in high demand to make hand sanitizer — not only from the organic wheat he used for TOPO’s vodka, but from unsold beer that distributors brought to him for free. “It became clear that making hand sanitizer was a possible way for us to survive,” Maitland says. “I gave away fifty percent of all the hand sanitizer that we made, and that was still the very best year of sales in the history of the distillery.” TOPO eventually closed in February 2023.

Another distiller in the South (who prefers not to be named) stopped producing spirits in March 2020, with intent to close, but also turned to making hand sanitizer in response to the crisis. “I was actually able to make a lot of hand sanitizer in March and April of 2020, which helped me walk away in a better financial position,” he says. This distiller never resumed spirits production and sold off his remaining inventory in 2023.

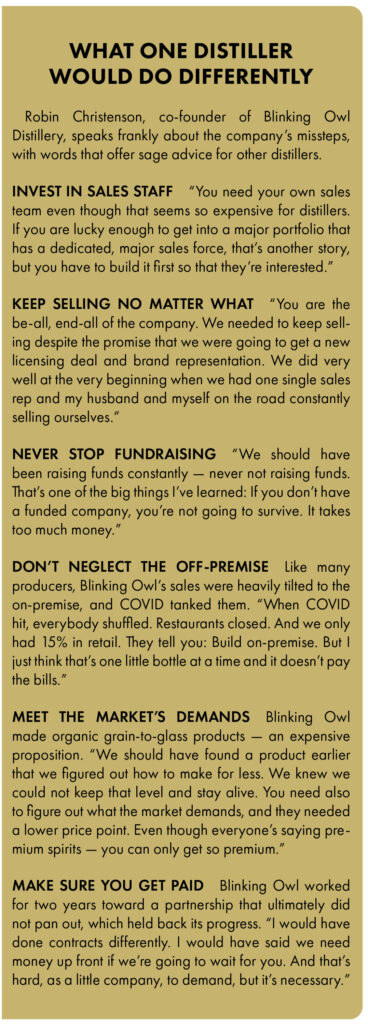

Blinking Owl Distillery in Santa Ana, California, which opened in 2016, also saw its best sales period during COVID, thanks to hand sanitizer that it was able to sell nationally. “That lasted about a year and a half and then that all, obviously, dried up very quickly,” says co-founder Robin Christenson. But, she adds, the distillery invested the additional revenue into opening an on-site restaurant that would allow it to sell spirits during the state’s prolonged shutdown period. The challenges of running that business alongside a production distillery, plus a partnership that fell through, forced Blinking Owl to shutter in 2023, though a potential acquisition deal was pending at press time.

Causes of Closure

For all of these distillers, the decision to close came after years of operation — and struggle. Both of the Southern distilleries were located in control states that offered few, if any, advantages or breaks for locally produced spirits. In fact, for most of TOPO’s life span, Maitland pushed tirelessly to change North Carolina laws to help local producers compete, at one point even using his own money to hire a lobbyist to work in the state legislature.

“We had to fight through all this stuff just to get on the shelves at the ABC store and to just be something that a restaurant or bar could purchase,” he says. North Carolina devolves control to 168 county and municipal ABC boards, which presented almost Kafka-esque hurdles at times, as a supplier must navigate each one individually. Among other challenges, Maitland discovered that there were informal stock lists that shut out less prominent companies from supplying on-premise accounts.

He also realized that many store managers lacked any desire to support local producers. Maitland relates the story of an ABC store that bought one case of TOPO’s Eight Oak Whiskey a week, stocking it on Tuesday and selling out by Thursday. Noting the trend, he suggested that they increase their order to avoid out-of-stocks. “The manager says, ‘No, I like selling out on your stuff because then I can direct people to buy stuff that otherwise isn’t selling,’” Maitland recalls. That was the moment, he says, “I realized I can’t win.”

Distillers also cite inadequate support on the wholesale side as playing into their struggles. Though securing distribution initially seemed like a win, the realization that they’d need to hire their own dedicated salesperson — and invest heavily in supporting sales and marketing — usually came as a surprise and was often simply not in reach financially.

“Nobody will sell your brand except you,” Christenson says. Blinking Owl actually did employ a California salesperson, but as the distillery expanded, the founders weren’t able to sustain focus on that part of the business, and sales suffered. “We started dividing ourselves between the restaurant, which was all-consuming to get started, [and everything else],” she says, adding that, in hindsight, that energy should have gone into sales.

Divided duties and being spread too thin were other common challenges. The unnamed Southern distiller says he was a one-man show, splitting his time between production and sales, which meant neither area received the attention it needed. In addition, he was restricted in tasting room samples to just four quarter-ounce pours and prohibited from selling bottles on-site.

And sometimes, distillers admit, they just made the wrong decisions or suffered from bad timing or the vagaries of the economy. Maitland, who has long operated a successful brewpub, opened an event space at the same time as TOPO Distillery, but it failed to take off amid belt-tightening at the nearby University of North Carolina, which was anticipated to be the biggest client. With each business tied to the other, the event space’s circumstances complicated things for the distillery, making it harder for Maitland to pivot when needed.

In addition to the unforeseen effect on sales and production that came with its restaurant, Blinking Owl spent years engaged in developing a national partnership that didn’t pan out. Christenson says that if she could do it over again, she would never have spent that time waiting for the deal to go through; she’d have continued to raise funds and focus on sales.

Arcane Distilling in Brooklyn, New York, founded in 2017, also sought a partnership to ensure its survival after a key supporter pulled out when “their priorities and appetite for risk had changed,” CEO Brian Thompson says. “We spoke to a number of potential new investors, but we were unable to find a scenario that worked for us. Unfortunately, we could not come to terms with any other parties that made sense for the existing owners or that were in the best interest of the company.” Arcane closed in 2023.

All of these factors ultimately played into the simplest and biggest reason for these distilleries’ demise: They just couldn’t make the numbers work. “We have struggled through seven years and never felt funded; always felt behind,” Christenson says. “We were always paid less than everybody in the company. Last year we made $22,000. We’ve sold everything for this.” She mentions selling two cars and her own wedding ring to keep the business afloat. “That’s how we’ve been around this long. We’ve sacrificed everything.”

Owning Both Failure and Success

Owning Both Failure and Success

But for all the struggle and heartbreak, these distillers remain proud of what they accomplished. Maitland points to the fact that his spirits were always made fully in-house from local grain, never sourced or rectified, as a point of distinction. And, he says, “My biggest contribution was to help create a playing field [in North Carolina] where there is a viable business model for a microdistillery — you are a destination in some way. Whether that means you’re a restaurant or you’re a farm or you’re whatever: People are coming for an experience that includes the distillery.”

Christenson says that despite all the setbacks, she feels confident that Blinking Owl has made a significant impact on craft spirits. “This has taught us: We have a seat at the table,” she says. “We’ve had big companies interested. We obviously are known and have a great reputation; we have an amazing product …. We just put all our eggs in one basket and unfortunately that didn’t work out in our favor.”

In the end, the forecast isn’t entirely dire. Owens says that a pattern of closures is part of a maturing industry. “The industry’s 20 years old. The first 15 years, we saw lots of entrances and very little exits,” he explains. “There’s going to be a new normal of entrances and exits into the market as the whole industry grows and gets more stable.” The number of new DSPs is climbing again, and investment into craft spirits continues to pour in. “There’s still a huge amount of investment and a huge amount of people that see potential in microdistilleries,” Owens adds.

But as the industry matures, the factors that drive success are changing — or perhaps just crystallizing. Craft distillers say that they need more support from their local governments, such as the ability to sell on-site, offer cocktails, and — especially — ship their spirits directly to consumers. And they acknowledge a need to become savvier with their business models, invest more in sales and marketing, build up their visitor experiences, and focus relentlessly on creating revenue.

Even that might not be enough — but it won’t stop distillers from trying. Clear-eyed and sanguine, Christenson knows that she’s taking something of great value from her experience. “If we’re going to own our failure, we have to own that we are the ones that got that success as well,” she says. “It wasn’t a happy accident.”