The world’s newest single malts aren’t from Scotland, but from America. In July 2022, in response to petitions from distillers in the industry, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) finally proposed to give American single malt its own legal standard of identity. It’s an exciting day for craft distilling, but we didn’t get here by chance. It took years of concerted effort from American single malt producers to convince the TTB to recognize this nascent category, and now, they’re celebrating a long-awaited win.

The New Standards

The proposal suggests that spirits labeled American single malt whiskey must be:

- Sourced from a fermented mash of 100% malted barley

- Mashed, distilled, and aged in the U.S.

- Distilled entirely at one distillery

- Distilled to no more than 160 proof or less

- Stored in oak barrels not exceeding 700 liters

Let’s unpack this. First, it must be made from 100% malted barley. As of today, a 100% malted barley whiskey would legally be classified as an American malt whiskey. The current regulatory code for American malt whiskey more closely resembles bourbon and rye: It requires a new oak barrel and a mash bill of 51% malted grain or higher. But creators of American single malt aren’t trying to make bourbon-esque malt whiskey; they are trying to rival the quality of the Scotch and Irish single malts dominating the international market.

To be clear, American single malt is not trying to be Scotch in America. Very few American distillers are trying to make a traditional Scotch profile. Many are opting for regional recipes that highlight local ingredients like mesquite smoke, local oak, and locally grown barley. Matt Hofmann, Master Distiller from Westland Distillery, says it best: “Our decision to produce single malt whiskeys is not born of a desire to simply replicate the exceptional whiskies produced more than 4,000 miles away. Rather, it is driven by a belief that we must make a product that reflects the distinct character of the place we call home.”

Second, American single malt must be mashed, distilled, and aged in the United States. The beauty of American craft distilleries is that no two single malts will taste the same, even if they follow the same parameters. The use of experimental barley varieties, experimental casks, and the wide variety of temperatures, ingredients, and other elements of terroir in the U.S. all contribute to unique regional whiskey flavors.

Stranahan’s, for example, is made from Rocky Mountain snowmelt and a proprietary blend of malted barley including two-row pale and some darker malts. Its production process is shaped by the high altitude and cold weather. The resulting whiskey is described as falling somewhere between a Scotch and a bourbon. Meanwhile, Tate & Company Distillery’s process runs against the clock, as the unpredictable weather in Texas makes aging whiskey for many years difficult. Compare that to Westland in Washington, which uses casks made from local garryana oak to age their single malts. The distillers’ choices are shaped by their environment, even if modern technology means geography doesn’t dictate everything. As Hofmann explains, “We’re not doing this for the sake of being local; we’re doing it because what’s available locally can make world-class whiskey.”

Third, American single malt must be distilled entirely at one distillery. It’s a common misconception that the word “single” in single malt means made from one single grain, but the word “single” actually means from one single distillery. When you buy a single distillery product, you are purchasing the specific character that the distillery is striving for. You want the flavors of that distillery and that distillery alone. It allows each producer to create their own identity while simultaneously creating trust from the consumer that when they order a St. George American single malt, they won’t be getting a blend of malt whiskeys from Kentucky.

Fourth, American single malt must be distilled to no more than 160 proof. If you’re in Scotland and you’re making grain whisky for a blend, you want it to be neutral in flavor so that you can change it as needed. That neutral profile is created by distilling grain up to 190 proof. You’re not going to get a lot of nuanced flavor out of anything distilled that high. That’s great for blending, because blenders are trying to diminish the unique characteristics of the whiskey and blend it into something smooth and consistent. Single malt, on the other hand, is all about emphasizing the singular characteristics of the distillery and the grain used.

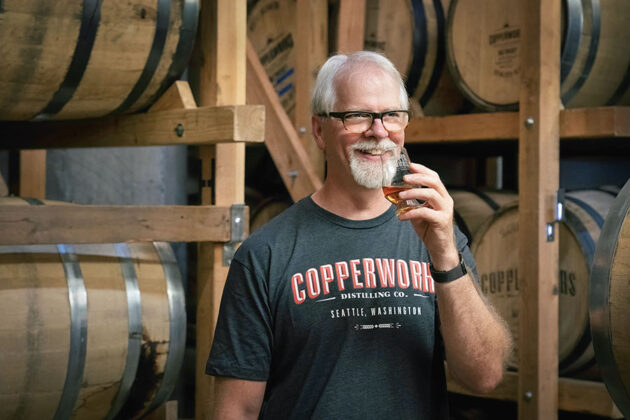

Fifth, American single malt must be stored in oak casks no larger than 700 liters. Traditionally, new white oak barrels have been the North American standard for aging whiskeys, but in this category a used barrel is legal. According to Jason Parker from Copperworks Distillery, the ASMWC wanted to be more flexible than most American whiskey, so they allowed used casks. The distiller can choose ex-bourbon casks to utilize the mellow vanilla notes that make the perfect backdrop for a clean single malt, or they can use new casks or casks that previously held Port, rum, tequila, or other products. As for capping the size of the barrel, the standard barrel size is around 53 gallons or 200 liters. You can imagine how large the proposed 700 liters is. At that point, the barrel becomes unwieldy and doesn’t impart much wood character into the whiskey, so capping the size ensures wood flavors are actually matured into the final product.

All five of these standards were introduced, discussed, and proposed by a group of eight distilleries who formed the initial ASMWC in 2016. How the group came about is just as fascinating as the whiskey itself.

The American Single Malt Whiskey Commission

The big players have dominated the bourbon market over the last 30 years of craft distillery growth, so it made sense for the smaller distilleries to trailblaze a different path. Some began creating single malts to showcase their unique qualities. The only problem was that the American definition for malt whiskey only required 51% malted barley. This meant a lot of inconsistent products were released into the market, which created consumer confusion. A customer would try a single malt from one distillery, then try one from another distillery that was a completely different product.

Many distillers wondered how to educate their patrons and protect the quality of the whiskey they produced. Japanese whisky was also experiencing a collapse in consumer trust when opportunists began sourcing spirit from other countries, bottling it in Japan, and then selling it at astronomical prices. American single malt distillers knew they had to get ahead of things.

In 2016, the ASMWC was formed. Jason Parker of Copperworks describes how the commission came together:

“There was an email from Matt Hofmann from Westland Distilling that catalyzed the conversation. He sent it to folks he knew were going to be making 100% malt whiskey, so about eight or nine distilleries. Copperworks didn’t even have our whiskey on the market yet! The request was to go to the American Craft Spirit Association meeting in Chicago and get together to talk about the future of whiskey. We all sat around this big table in a room at Binny’s with the agenda of creating some rules around a category of whiskey we were going to call American single malt before someone else does. We said, ‘Let’s try to own this.’”

The meeting itself was short and sweet. They spent a little under an hour together and concluded with all eight distilleries on the same page. The distillers all wanted to follow American whiskey rules where they made sense and Scotch rules where those made sense, while still allowing for innovation in the category. Debates were mild and included conversations around whether you could ferment anywhere in America or if it had to be done at the same single distillery as distillation. They eventually decided to allow fermentation anywhere in the United States. Another debate included a discussion on whether non-barley could be allowed. For example, can a single malt whiskey be made with rye malt? They decided no, but that you could have a single rye malt whiskey; the word must be in the title. Otherwise by default, it must be barley.

After the initial meeting, many thought getting others involved would be a challenge. However, it proved to be surprisingly easy. Virginia Distillery’s Gareth Moore says “recruiting other distillers to the cause was not particularly challenging once there was an initial critical mass, which is a testament to the sheer volume of ASM producers. Creating the proposed standards was something that we anticipated to be a hotly debated topic, but ultimately the relatively simple standards were quickly accepted by the vast majority of producers.”

Adoption was easy because those standards were chosen with a few principles in mind; they reflected consumer expectations based on definitions of single malts from Scotland, Ireland, and other countries, and they were also broad enough that they did not stifle the innovation of a nascent category. Outside of those principles, the most complex issue was navigating the existing constructs of TTB definitions of classes and types of spirits. And, of course, getting the TTB to change the rules.

So, what comes next? The new proposal was open to the public for feedback for 60 days, ending on September 27, 2022. Barring any surprises, the American single malt category will be made official. Once it has its own place in the world, what that means will be up to us all: the consumer, the producer, the distributor and the stores, the international market, and local markets. Who knows if American single malt will ever rival bourbon or Scotch in the world, but at least now it has a chance.