Most stories about spirit proof mention British Navy proof, because it’s such an amazing contrast to our present day reality and a nifty story. But it also neatly frames the entire complex of issues that gave rise to our current ABV standards.

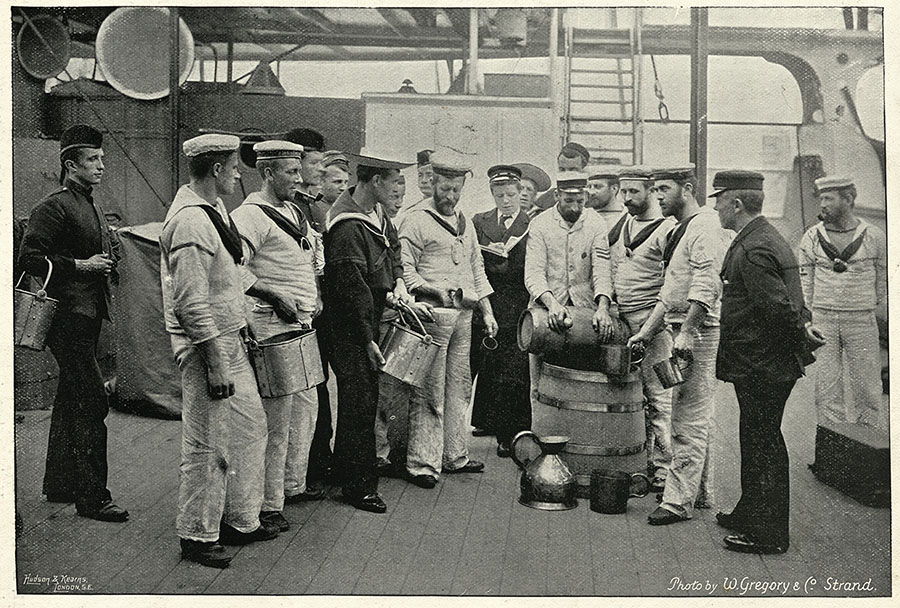

The story goes like this: Beginning in the 17th century, British sailors received a daily allotment of rum. In order to ensure that they weren’t being cheated, they would occasionally test the proof of their rum by pouring it on gunpowder and trying to ignite it. If it was at high enough proof — exactly how much is a matter of discussion, but definitely above 50% ABV and most likely 54.5% ABV or above — it would ignite, proving that the sailors’ rum wasn’t being diluted.

It’s worth considering what it means that sailors were given a daily ration of rum. Today the standard script on U.S. bottles of alcoholic beverages states that “(2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems.” Imagine what operating a massive, valuable ship on the high seas under the influence of alcohol must have been like. It was dangerous and tough, and people got hurt all the time. And yet they drank. It was part of the very life of a sailor — and everyone else. The British Navy maintained that tradition, but the rest of society gradually caught up. The 19th century was widely besotted — with professional drunkenness sanctioned by the British Navy and pretty much everyone else — including elections, which were run on free booze. Forget three martini lunches, this was a life of inebriation.

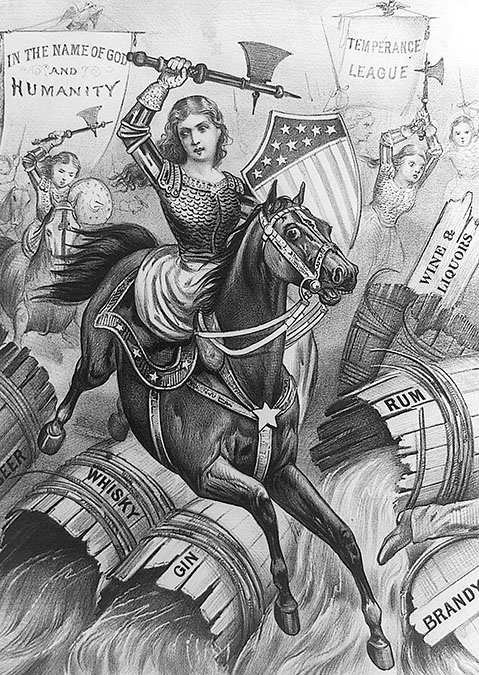

The British Navy wasn’t an outlier; drunkenness was a major issue anywhere distilling had taken hold. And that inspired a mighty reaction. The 19th century was also the origin of the temperance movement to drink less or, ideally, not at all, exactly because so many people were so drunk so much of the time. The foreword of The Alcoholic Republic: An American Tradition, by W. J. Rorabaugh, sums it up: “Between 1790 and 1840, Americans drank more alcoholic beverages — nearly a half pint of hard liquor per man each day — than at any other time in our history.” According to our current standards, that means that most American men were drunk most of the time. The damage to public health was massive: Newspapers were full of stories of drunken violence and men who left their families. It’s no wonder that a huge temperance movement gained steam until it all came to a head in the first decades of the 20th century.

The Temperance Movement

Along with abolition and religious revival, temperance was a major grassroots movement of the 19th century. But it never managed to break through the political and business nexus until national interest forced the matter. In Britain, the motivating factor was the First World War.

Prime Minister David Lloyd George had long tried to implement some form of temperance, but the war finally provided an opening that the whiskey lobby couldn’t undermine. Rod Phillips, professor of history at Carleton University, Ottawa, wrote to me, “In Britain, the government wanted to reduce the alcohol level of drinks so as to minimize drunkenness leading to absence from work that would affect war production.” In 1917, after years of negotiations between the government and distillers, they agreed on a 40% maximum level in general, and a maximum of 28.6% ABV in locations critical to the war effort like munitions factories and environs.

This was an international phenomenon. Russia had decreed prohibition in 1914, and the United States followed suit with the 18th Constitutional Amendment in 1920. Phillips notes that, “like a lot of wartime measures, the 40% rule outlasted the war itself.” When the U.S. repealed Prohibition in 1933, 40% was widely adopted here as well. While it wasn’t a ceiling — spirits could be stronger — governments generally taxed higher ABV products at a higher rate. That incentive, combined with the corporate desire to maximize profits from production, meant that many producers stuck to the minimum ABV allowed by law. In the words of Lance Winters, St. George Spirits’ master distiller, “taxes weren’t being levied on a per proof gallon basis, which meant that a distiller could maximize tax savings by lowering the alcohol content.” He calls 40% “the sweet spot that allows spirits to read as non-aggressive, while still having at least some recognizable character.”

And that was and is enough for most consumers and the industry as a whole. The minimum 40% ABV level allows everyone in the production chain — distillers, distributors, bars, retailers — to have a standard and sell a spirit at a decent price. It seems like consumers either don’t care or like it this way. The vast majority of spirits are consumed in cocktails; that 40% level is expressive enough to give a cocktail identity without overwhelming the average drinker. Plus, you can sell more cocktails. It’s a virtuous cycle. Ivan Saldaña, co-founder of Casa Lumbre Spirits and master distiller for several of the portfolio’s brands, says, “It is not only that you can make more bottles with less alcohol, but also that it’s more approachable. That’s what brands want more and more.”

Culture, Flavor, Aroma

So is 40% ABV the optimal level for spirits? Winters notes that “At St. George Spirits, we largely ignore the 40% standard. Spirits like gin are able to show up much better in a cocktail at a higher ABV, so we bottle at 45%.” Saldaña says that the chemistry behind it is clear: “The more alcohol, the more perfumed it is” — although adding water in the glass just before drinking can sometimes amplify the perception of aromatics due to exothermic reactions that boost volatiles. But are those aromas and flavors really that important to most people? Saldaña noted that most people are drinking spirits in cocktails where those aromas aren’t as important.

An equilibrium between commerce, public health, and taxation isn’t all that’s at play. Saldaña is insistent that culture is also a critical piece of the puzzle. He says that “how much alcohol depends on the culture, what you’ve been drinking.” Wine- and beer-centric cultures like Spain and Italy may find even cocktails too strong, while others, like his own in Mexico, are accustomed to sipping straight spirits. “Mexico is a sipping country,” says Saldaña. “We sip much more than anywhere else, so we prefer the under 44% proofs.”

Higher proof spirits still have a place among aficionados, and definitely within the craft distilling audience. Winters notes that St. George bottles its Baller single malt at 47%. He says lower ABV spirits have lower concentrations of aromatics, as well as higher surface tension, making it more difficult for aromatics to break free of the glass. “While we as drinkers tend to add a splash of water to whiskey to open it up, that’s done in the glass, where we can enjoy compounds breaking free of one another. If that water is added in a vat prior to bottling, you stand a good chance of losing them to the atmosphere.”

Producers of products like mezcal or Haitian rum have long known that higher ABVs can be more expressive, and their spirits are often marketed that way. But the movement toward higher ABV spirits in the past decade appears mainly restricted to smaller batch craft spirits and various whiskeys. While many American distilleries offer some higher proof spirits, they are often restricted to small projects. At St. George, for instance, absinthe is bottled at 60%, but vodkas are bottled at 40%. Leopold Bros bottles its vodka at 40%, while absinthe is bottled at 65% and navy strength gin at 57%.

While Saldaña says appreciating spirits is a highly subjective experience, he and most distillers seem to understand that they are designing gins, vodkas, and many whiskeys almost exclusively for cocktails. This reflects one of the fundamental tensions in the distilling world, and one that has a significant impact on bottling strength: Most products are still consumed in cocktails, so designing spirits for that use is critical for a product’s success. For distillers, that means being thoughtful about consumers’ end use of your product is the ultimate key for choosing the right bottling strength.