Marauding pirates and salty nautical adventures on the high seas, the horrors of slavery and triangular trade — these are some of the all-too-common modern day associations with the spirit of rum. But long before rum was relegated to the sandy cultural shelf-space of warm tropical breezes and Tiki bars, it reigned as the king of spirits in America.

Through rebellion and war with England, rum lost its brief shining moment as monarch in colonial Camelot, and the crown was slowly usurped by whiskey. Although the category of rum in general began staging a long comeback with the romance of Prohibition-era Havana nightclubs and mid-century umbrella drinks, it has only been in the past ten or so years that craft distillers have looked to claim it again as the American Spirit.

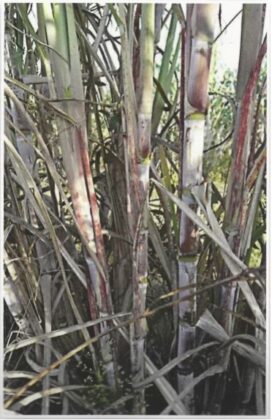

Rum came to prominence in the North American colonies as the British Islands began exporting it in return for New England lumber and cod. It did not take long before the American colonists developed a real thirst for rum, and savvy Yankee businessmen began shipping molasses from the Caribbean and started distilling it themselves. They would then ship the finished product to ports in West Africa, where they exchanged the rum for slaves. Finally, ships bound for the Caribbean and South America carried slaves to work the sugarcane plantations, where cane was harvested and molasses was produced. And then the cycle would repeat itself.

The gradual decline of rum in the states came about with the American Revolution and the disruption of the triangular trade system through war. Whiskey consumption began to rise as more of the US population moved westward, making use of grains more economical than shipping molasses from the Caribbean. Rum continued to slowly decline, and by the time of Prohibition, production had ceased in the US. Although Prohibition did not stop the import or production of illegal liquor, it did help give rise to the notion of rum as a low-quality product fit only for mixing. Rumrunners could buy cheap rum in the islands, and sell it for a handsome profit stateside.

Rum is currently experiencing a healthy revival on the cocktail scene and in the spirits world, but can it once more claim title to the throne in the United States? And can American craft rum distilleries claim a decent share of this market? I interviewed several rum distillers and experts from across the United States to examine this question. Through the interview process, it became clear that there are some significant hurdles facing American rum distillers that affect the continued growth of rum as category. Some producers see these issues as opportunities to be creative, while others view them as real challenges to their businesses. Listening to these producers gave some insight into just how nuanced and complicated these issues can be.

Whether A System Of Classification?

Phil Prichard, proprietor of Prichard’s Distillery in Kelso, TN, writes that the nomenclature provided by the US government does nothing to describe the numerous styles of rum, nor does it say anything about the wide variety of flavored rums produced at different proofs. The current disorderly system, which has not been codified under US law, describes rum mainly by color, such as white, dark and aged. Under these loose classifications, dark rum can be made with the addition of caramel color, thus giving a false impression as to its ang. And age is not a good criteria either for describing rum because there are no provisions that address how it was aged, or for how long. With all the new rums coming on the market, not to mention the ones already on the shelves, Prichard argues that there needs to be a better way to quell consumer confusion and to adequately describe rum to the growing number of enthusiasts.

Indeed, if one examines the definition of rum under the CFR’s Standards of Identity, class 6, the statute provides no more direction than the following: “Rum” is an alcoholic distillate from the fermented juice of sugar cane, sugar cane syrup, sugar cane molasses, or other sugar cane by-products, produced at less than 190° proof in such manner that the distillate possesses the taste, aroma and characteristics generally attributed to rum, and bottled at not less than 80° proof; and also includes mixtures solely of such distillates.

Prichard advocates the development of a system of classification to be used by distillers that would help consumers make more informed, intelligent decisions when assessing and buying rum. He posits the use of three broad categories, Traditional, Classical, and Industrial/Refined, each with a subcategory of white, dark and certificate aged. The Traditional category would broadly encompass those rums that are produced from fresh squeezed cane juice, while the Classical category would be made up with rums that are produced from sweet, table-grade molasses. Finally, the Industrial/Refined rums would be those that are produced from black strap molasses.

Luis Ayala, international rum consultant and president of Rum Runner Press, Inc., also believes that the craft rum industry is at a crossroad in its need to develop a comprehensive nomenclature and standardization of terms. This would help guide the growing body of rum consumers, as well as maintaining quality standards within the industry. However, actualizing this might be a different matter. For instance, a rum distiller who did not adequately plan both financially and technically for his or her distillery might have the good intention of selling an aged rum, but later find themselves in a position of having to bottle and sell the product before it is truly matured. Consumers used to buying aged rums may buy the product at a high price point, only to later discover upon tasting that the product is not truly what it purports to be. Ayala believes that the craft rum industry would not back a government classification system because it would take away their freedom to decide when to release their products, although placing spirits prematurely on the market can also damage the reputation of the industry as a whole.

Some distillers see freedom for creativity in the vague nomenclature for rum, and the sale of such experimental products can be lucrative. Unlike the US nomenclature for whiskey, which sets out very specific types of whiskey and how it must be produced, the lack of such a structure for rum allows producers to create new flavor profiles without having to worry about where to situate their product within the proper category before submitting their labels for COLA approval. Such vagueness is what allowed Andrew Causey, president of Downslope Distilling in Englewood, CO, to take a chance on buying previous use Hungarian Tokaji barrels and experimenting with aging his rum in them, and then releasing the product when we felt it was ready. He also aged some of his rum in Cabernet Sauvignon and other wine barrels. He says that the growth curve for these products has “surpassed those of the white and gold rums.”

Because the Standards of Identity are silent as to how and for how long rum should be aged, some distillers have been able to experiment aging their products with new, charred oak barrels. Others have experimented widely with wash recipes. They tend to agree that it is great to have the freedom to release their products when they see fit, and to have room for creative expression.

Consumer Education: “Not All Rum Is Bad”

Another significant challenge for American craft rum producers is that many consumers have preconceived notions of what rum “should be like.” These notions are usually based on negative experiences with poor quality distillates, or on the belief that all rum should fit the flavor profiles already established by the various styles of Caribbean, Central and South American products. This issue is partly a product of the historical experience of Prohibition, as noted before, since cheap rums were ubiquitous on the black market and the public perception of rum as a cheap mixer became ingrained in the American drinkers’ collective consciousness. It is equally due to the fact that there is a plethora of inexpensive, mass-produced, big-name brands of rum on the market today. And finally, from the time of Prohibition until the mid to late 1990 s, there were no American distillers producing rum. The general public has only had the Islands and South American rums to use as reference guides, and the cultural associations that attend them.

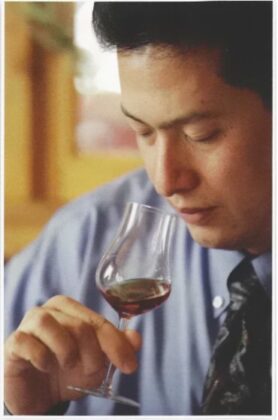

However, rum producers have differing views as to just how big of a challenge consumer education is for them. For Kelly Railean, proprietor of and distiller at Railean Distillers, at the Eagle Point Distillery in San Leon, TX, consumer education is crucial for sales, and in order to teach people that rum can be a great product in its own right. This is not a big issue on the Gulf Coast where she distills, since the area boasts a large sailing community with many rum connoisseurs. Rather, getting the word out past the seaside community is the real challenge. Railean accomplishes this through hosting distillery tours, tastings, speaking at symposiums, and giving lectures. She explains that when you tell people how it is made differently from mass-produced products, first by using quality molasses and then doing every aspect of production herself by hand, “People don’t mind paying a couple dollars more for it. They realize that you can actually sip a fine aged rum the way you would a bourbon, whiskey, or a Scotch.”

Andrew Cabot, president of Privateer International in Ipswich, MA, views consumer education as “less of a challenge because of the general ‘Food movement’ in this country. People are a little more predisposed to listening these days.” Cabot observes that “there is a willing and able audience out there.”

More of a challenge for Cabot is the misinformation about rum that comes from marketing campaigns, as well as a bias by many rum experts towards Caribbean and South American rums. “Even experts promote biases, and they aren’t necessarily aware of them. Preferences are different from biases.”

Phil Prichard offers some insight as to how to address the Caribbean and South American cultural associations with rum by educating his consumers on the history of rum and letting them know that his rums are American-made. Prichard explains, “There are a lot of people out there who don’t realize that America was the largest producer of rum prior to the American Revolution. And people also expect rum to be cheap. If you get them to buy an $80 bottle of rum, which we have, you have done a marvelous job of educating your consumers that not all rums are white, or cheap, or made with back strap, or made in the tropics.”

Andrew Causey wraps up the issue of educating consumers through his observation that “there are some really, really good rums out there, and some really bad ones, and most people have only tasted bad rum. It is our responsibility as craft distillers to change that.”

Competition With Whiskey, Vodka, and Foreign Rum Markets

Another big challenge facing the American craft rum industry comes in the form of stiff competition with popular whiskey and vodka categories, followed by foreign rum. According to the spirits category table reports released by DISCUS for 2010, 24.9 million nine-liter cases of rum were sold that year, while 59 million cases were sold, followed by 47 million cases for all whiskey categories. The good news for rum producers, according to a 2010 report released by Impact Databank, is that rum consumption has doubled from roughly 11 million cases in 1994 to over 24 million cases in 2009. But with craft spirits only comprising about 1% of total distilled spirit sales, with most of those sales for vodka or whiskey, craft-produced rum is still only a drop in the alcohol bucket.

When it comes to American craft distillers competing with non-domestic produced rums, Kelly Railean points out that both tough federal and state governmental regulations give foreign producers the upper hand. For instance, in order to comply with such regulations, she must increase the price of her products to stay afloat. Although certain regulations, such as environmental laws, can be a good thing, overseas producers don’t always have the same costs of compliance and can sell their products more cheaply. In the state of Texas, she has to sell her products directly to a licensed distributor. And is so often the case, the distributors tend to promote giant brands like Bacardi rather than promoting small brands because of the much larger financial return.

As noted above, most of the producers and experts I interviewed observe that consumers usually expect rum to be cheap as compared to other spirit categories. “People will not pay $40 for a good bottle of rum when they can buy it cheaply from Captain Morgan,” Luis Ayala laments, “but they don’t mind paying $40 or more for a good bottle of vodka or whiskey. In this way, although the volume of sales has doubled for rum since 1994, rum is still lagging behind other spirits in what people are willing to pay.”

Phil Prichard realized in the mid-2000’s that rum can often be a seasonal item and harder to sell year-round than whiskey. Early in his distilling career, a distributor once told him “people like rum, but they love whiskey.” And as he noticed his rum sales begin to level off, he began producing whiskey so that his distillery would see continued growth.

The Forecast For Rum

The rum producers I spoke with all exhibited a “cautious optimism” regarding the future of American made rum. Clearly, there are several hurdles that must be addressed as rum continues its gradual ascent. And while these distillers want rum to be at least as popular as whiskey and vodka, they realize that it may never completely catch up in sales with these categories. Yet, there is a tremendous amount of room for distillers to be creative in experimenting and producing new flavor profiles, thus developing a variety of styles of the new breed of American rums. As Andrew Causey assured me, “Rum is going up and up, and there is plenty of room to grow. The sky is the limit.” And that is great news.

(Editor’s Note: Nancy Fraley is currently producing a Craft Rum Aroma Wheel for use as both an industry tool and rum consumer education guide.)

These two classic rum cocktails

are from Martin Cate, proprietor of Smuggler’s Cove,

the famous rum bar in San Francisco:

Daiquiri #3

0.5 oz fresh lime juice

0.25 oz fresh grapefruit juice

Dash superfine sugar

0.25 oz maraschino liqueur

2 oz light, dry Spanish style rum (or your favorite — it’s a flexible drink)

Combine all and shake and fine strain into a chilled cocktail glass.

Bumbo

2 oz full bodied, pot-still rum

0.25–0.5 oz demerara simple syrup

Stir on the rocks in an old-fashioned glass and top with fresh grated nutmeg

Also originally published with this article:

5 Rums Every Micro Distiller Should Try

Ambiguities in the Legal Definition and Interpretation of Rum