On the evening of April 4, 2023, many of the members of the Manhattan Whiskey Club (run by yours truly) got their very first taste of American single malt. The club gathered at DXA Studios for a preview tasting of Lost Lantern’s newest Single Distillery Series led by founders Adam Polonski and Nora Ganley-Roper. The whiskeys ranged from a blend of American single malts to distillery-specific releases from Arizona’s Whiskey Del Bac, Oregon’s Westward Whiskey, Washington State’s Westland, and Texas’s Balcones, among others. I say this as a longtime whiskey fan: The reaction of our club to these whiskeys was a sight to behold. We love whiskey, but a good portion of the members define themselves as Scotch fans or bourbon and rye fans. Those distinctions were shattered that night. Those whiskeys were some of the best-received we have had in seven years of the club’s existence.

Whether you follow publications focused on spirits or the vaunted pages of The New York Times, the phrase “American single malt” has been on peoples’ lips. The American Single Malt Whiskey Commission was formed in 2016 by a group of producers who gathered together to develop a set of standards for the new category of U.S.-made single malt whiskey. Six years later, in 2022, the TTB proposed to give American single malt a well-defined legal standard of identity. This is the year that this new whiskey category is expected to get its official coming-out party, and you as a whiskey fan (or producer) need to be ready.

As I saw at that Lost Lantern tasting in Manhattan in April, American single malt has the ability to blur the lines of existing whiskey categories — to pull from the traditions of many different styles of whiskey and to allow experimentation with flavor and casks that might not be possible if one was crafting a bourbon or a Scotch. With a proposed legal standard on the table and that long-awaited milestone waiting in the wings, the real question is: What’s next?

Education Is Essential

Nora Ganley-Roper, co-founder of Lost Lantern, feels that education is the primary initial task facing the industry. “Honestly, it’s not even really the next challenge, as it’s something we’re already working on,” says Ganley-Roper. “But regardless, helping people understand why American single malt is so special is a very important undertaking. Getting people out of the ‘but this doesn’t taste like Scotch’ or ‘this doesn’t taste like bourbon’ dichotomy requires both an understanding of what single malt is, and why it tastes so different when it comes from the U.S.” Steve Hawley, president of the American Single Malt Whiskey Commission, agrees. “[The] TTB’s ratification of a new Standard of Identity will draw a lot of attention, but building awareness will still continue to be a main priority for us,” says Steve.

Jared Himstedt, head distiller at Balcones, says he’s focusing on first things first. “The most immediate challenge is getting the Standard of Identity passed through and official,” says Himstedt. Once that hurdle is cleared, the industry can begin educating not just consumers, but distributors and retailers as well, since landing space on menus and shelves will be essential to highlight the category.

Spirits writer Susannah Skiver Barton feels that distillers have done a good job educating the whiskey nerds (such as myself) as well as the trade, but the real next challenge will be getting solid retail placements and selling to consumers. “There’s a lot of great American single malt out there, but getting shelf placements and moving bottles is still really hard. This is tied into consumer awareness, which is still incredibly low. Consider that even a serious Scotch drinker often can’t tell you the difference between single malt and Scotch, and you start to see what American single malt is up against,” says Barton.

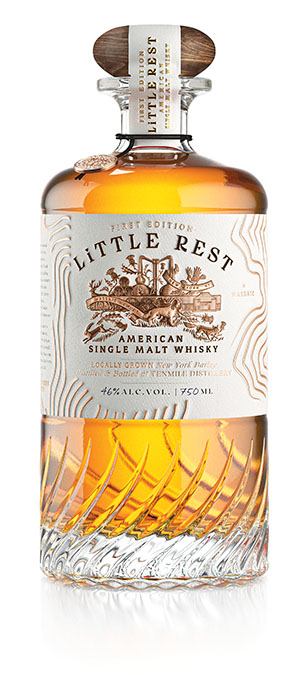

Joel LeVangia, general manager of Tenmile Distillery, a new distillery in New York State that will soon be releasing its first American single malt, is taking a geographically broader view. “I think the job of American single malt will be to prove it’s consistent with the highest international producers of single malt. Innovation or differentiation in American single malt has thus far been to ‘bourbonize’ it with charred new American oak barrels. Demonstrating the skill and expertise necessary to do the thing properly is much more interesting to me,” says Levangia.

Who’s the Consumer?

Sales are a perennial struggle no matter the category, and it’s often made more difficult by the sales channels available in the American market. In the USA, the current three-tier system of alcohol distribution was set up after the repeal of Prohibition. Each state handles it slightly differently, making this process a nightmare for smaller producers who can’t always afford the expense of a national distributor, the hassles of managing each state, or the cost of advertising their releases on that scale. To make this even more difficult, some states are control states, where part or all of the distribution tier, and sometimes also the retailing tier, are operated by the state government or by contractors operating under the states’ authority. In Europe, it is a lot easier for a producer to sell directly to the consumer, which is a boon to the smaller producer, who can cultivate fans and generate sales at a lesser expense.

American single malt’s primary market segmentation remains an open question, both in terms of what kind of consumers it attracts and the channels through which it will thrive. Adam Polonski, co-founder of Lost Lantern, feels that there are two main groups of American single malt drinkers.

“The first are people who are primarily fans of a particular distillery, often but not always one in their area. These whiskey drinkers are more loyal to the brand than to ASM as a category, and they may not drink widely beyond their preferred brand,” says Polonski. One example he offers is Stranahan’s, which has a devoted following in Colorado and nationally, especially for their annual Snowflake special release, but those fans don’t necessarily cross over to other American single malt brands. The other major segment of American single malt fans, according to Polonski, are “serious whiskey lovers who first cut their teeth on bourbon, Scotch, or other styles of whiskey and then discovered American single malt later, as they continued to seek out new whiskey experiences.” For him, American single malt’s future lies with drinkers who “grew up” with the category — for them, it will always have been a key part of the whiskey landscape.

Jared Himstedt thinks whiskey fans have “broadened their horizons” of late. For him, “the drinker who only drinks bourbon or Scotch exclusively is becoming a thing of the past.” If that is true and tomorrow’s drinker is open to new possibilities and profiles, it will help the category thrive. The way that Steve Hawley sees this playing out is that the USA “is far and away the primary market for ASM, and I would wager always will be. That said, we already have a number of producers exporting to markets across the world. As the category grows and gains more notoriety, that will only expand.”

LeVangia thinks that we have seen a method that works and can be applied here. “American single malt’s goal should be to win over the American Scotch whisky drinker. Japan has shown the way for how to do this: Adhere to traditional methods of Scottish single malt production and you can be very competitive very fast with large producers. You won’t make very much, but what you do make will be very good.”

When asked about ASM’s primary market, Barton thinks that what is true now will probably be true in the decade to come, namely “For most ASM distillers, their primary market is and should be their local/regional area. Neighbors are a receptive audience no matter what whiskey you’re making, and if you win your backyard, you have a solid foundation from which to grow. Ten years from now, ASM will probably still be a mostly regional play, although brands that have the volume to support wider availability may be succeeding nationally, especially if they’re able to self-distribute.”

What Will It Take for American Single Malt to Grow?

The issue of distribution, especially as it currently exists in the USA, will play a key role in either helping the category to grow or confining many of the smaller players to their home turfs. For both Hawley and Himstedt, the Standard of Identity is first and foremost in that fight.

“The SOI will definitely help,” says Himstedt. “We are going to have to keep chipping away at any misconceptions folks have around American single malt and get these whiskeys in front of folks who might be skeptical or just unfamiliar with the category.” Hawley feels that “the formalization of the category by TTB will be a monumental step forward for American single malt whiskey and serve to catapult the category quickly.”

Polonski is of the opinion that American single malt needs an affordable, accessible entry point to earn new consumers. He points out that “most Scotch lovers first started to explore Scotch through entry-level mass-market blends or through relatively affordable single malts like Speyburn or Glenfiddich. Likewise, bourbon lovers often start by falling in love with Knob Creek or Buffalo Trace before moving up to higher price points. Few people are able and willing to jump right to more expensive whiskeys like The Macallan, Bruichladdich, Booker’s, or Blanton’s.”

Direct-to-consumer sales also have the potential to radically alter the landscape for American single malt producers, especially small- to mid-sized ones. “Making direct-to-consumer sales easier/legal would be a boon to small players who don’t have the resources to support a traditional distribution push,” says Barton. Based on my experience with the Manhattan Whiskey Club, I wholeheartedly agree. Direct to consumer shipping would do so much to help all small distillers get their products to a wider audience clamoring for craft releases, be they American single malts, craft ryes, or other spirits. Changes in these laws would make these distillers less dependent on their home markets for expansion.

Innovation and Tradition

Polonski, with his constant interactions with so many small whiskey distilleries for Lost Lantern, has a firsthand glimpse into what a lot of brands are doing in terms of innovation and new product development. “Many distilleries have begun exploring cask finishes that are more regionally rooted than the worldwide tradition of sherry casks,” says Polonski. “Eventually, some cask types that are already used today will likely become part of a new American canon of whiskey maturation, as familiar to whiskey lovers as sherry or port casks are now. Apple brandy casks, tequila casks, beer casks, who knows what else!”

For him, a move to full-term maturation in “unique casks” will become more prevalent versus the finishes that are currently more common. He also thinks that “new types of smoke are also likely to become more prominent,” citing distillers experimenting with applewood, cherrywood, or seaweed smoked single malts.

Conversely, LeVangia believes that the practices of the past are the way to the future. “I hope that American single malt producers will not throw the baby out with the bathwater by completely reinventing the category,” he says. Instead, he’s more interested in malts that explore place and provenance. “I think American single malt has the opportunity to shift the entire single malt landscape by forcefully demonstrating that the Slow Food approach to whiskey production yields significant quality and flavor benefits. Shane Fraser’s [Tenmile’s master distiller and the former distillery manager of Wolfburn and Glenfarclas distilleries] low and slow approach at Tenmile Distillery has been largely written off in this age of mass market industrial production. It’s time we reexamined the merits of our forebears’ traditions.”

Himstedt has a similar perspective. “I think we are still in the middle of the arms race to find the most obscure finishing barrels, but that will get old soon,” he said. “I don’t want to show our hand, but I think the next layer down from the easy ways to differentiate expressions from finishing will be continued exploration around locality. There will be American single malt being made from barley that has literally never been used, cross-pollination of techniques from other spirits traditions, and deeper dives into a more philosophical and existential look at what it means to use one’s whiskeys to give voice to the entire living community where it comes from.”

Hawley is of the opinion that the ratification of a standard of identity by the TTB will create a surge in the amount of American single malt being laid down, with an increase in production from current producers and new brands both big and small entering into the market. For him, that surge and the new players will drive innovation. “Given the definition we’ve proposed (and the TTB has adopted) leaves lots of room for innovation and creativity, I think we’ll see a lot of new ideas emerge. Many think that regulations serve to stifle innovation but even in Scotland and other regions that have been making single malt for much longer,” Steve says, “it’s really tradition that limits innovation more so than regulations.”

We’ve already seen giants like Jim Beam step into this space with their Clermont Steep American Single Malt. I know from my conversations with brands like Frey Ranch, which is experimenting with a single malt and seems quite willing to enter this market when the time feels right, that other brands are also keeping a watchful eye on the category.

If the enthusiastic response of my whiskey club is any indication, the future of American single malt whiskey is bright. It has the flavors to make it distinct, distilleries with ambition and drive that have been awaiting this moment, and an expanding fan base that can help it grow both domestically and abroad. The road will have twists and turns, but for now, it’s an exciting new path to follow.