Have you ever noticed that there are two different spellings for whiskey? To be honest, I had not until I began working on the book A World Guide to Whisk(e)y Distilleries. Research for the book revealed that no distilleries — including those in Africa, Asia, Australia, Europe or the Americas — spelled whisky with an “e,” except those in the US and Ireland. This discovery inspired an excursion to find out why whisk(e)y has two spellings, and why the US favors the one it does. However, searching the Internet for answers only uncovered a heated controversy and unsubstantiated folklore.

Unsatisfied with what the internet had to offer, books on etymology, dictionaries, newspapers, massive book databases and style guides were the next logical sources that could track when and how the use of “whiskey” and “whisky” changed over time. Collectively these sources offer an explanation for why whisk(e)y has two spellings, and when the geographic nature of each spelling sprouted in the US, but the reason why the US came to favor “whiskey” over the alternative may not be recoverable from the historical record.

The best answer for why whisk(e)y has two spellings comes from etymology dictionaries. The Latin term for distilled spirits, aqua vita (water of life), made its way to the English isles in the Middle Ages. This term was translated into Gaelic as uisge beatha in Scotland and uisce beatha in Ireland. From 1583 to 1730 there were at least seven different anglicized versions of this Gaelic term, which included iskie bae and usquebea. However, in 1746 “whisky” made its first appearance in the recorded history of the English language with “whiskey” following seven years later in 1753. After this, no new spellings developed, which is likely due to the fact that the first English dictionaries soon began to appear and codify spellings.

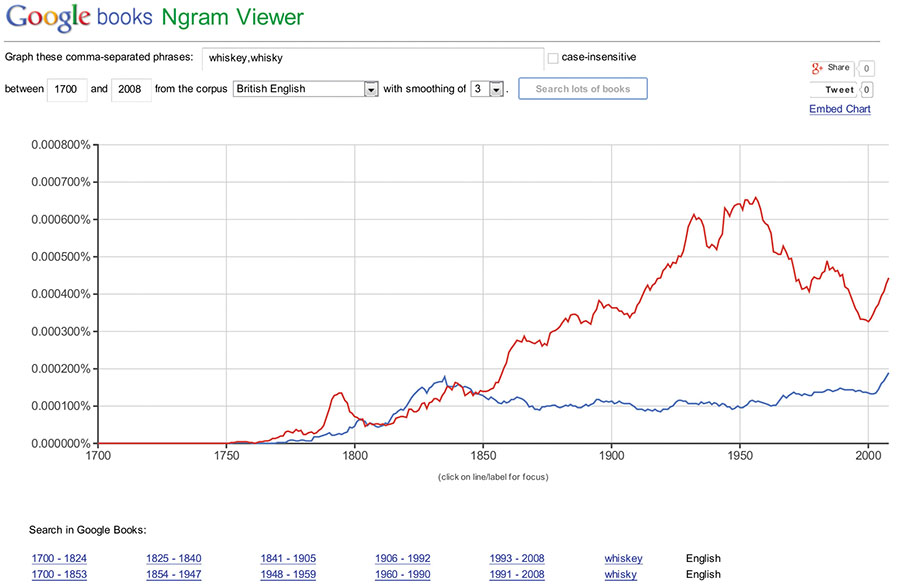

Using the Google Books database, it is possible to track how often a word or phrase is used over time as a percentage of all words used in the 20 million books Google has scanned. These “Ngram” graphs that are generated from the database make it easy to visualize how usage of words changes with time in, say, American English verses British English. In Figure 1(page 86), The Ngram graph of “whiskey” and “whisky” in British English corroborates the etymology dictionaries’ entry dates for each spelling, and it shows a significant point of divergence. Around 1850, the use of “whisky” grew rapidly while the use of “whiskey” stayed flat. One explanation is that this difference in spelling usage resulted from Irish distillers purposefully using whiskey instead of whisky as a point of distinction from Scotch. Without access to large collections of Irish and English newspapers and books that would be very difficult to prove.

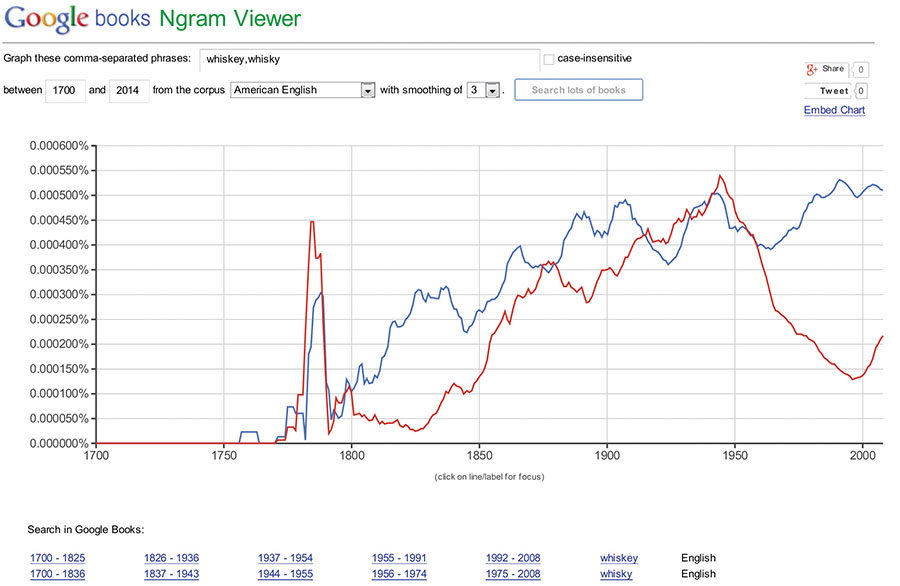

Meanwhile, the graph of “whiskey” and “whisky” in American English (Figure 2, page 86)) tells us a different story. Although “whiskey” tended to be used more often than “whisky,” their usage grew at a similar rate until 1960. After that year there was a precipitous drop in the use of “whisky,” until 1996 when its use began to rise again. Incidentally, the increased use of “whisky” correlates with the mid-nineties rise in Scotch sales and the launching of Whisky Magazine and Whisky Advocate. One could also argue that this graph supports Charles Cowdery’s claim that “whiskey” has been, is and should continue to be the preferred spelling in American English. He argues that like “color” and “colour,” “whiskey” is just one of many words in American and British English that has different acceptable spellings. Therefore, Cowdery posits, American writers should only use “whiskey” no matter where the spirit came from. However, US dictionaries, books and newspapers from the 19th and early 20th centuries paint a different picture. These sources demonstrate that while “whiskey” was used more frequently, both spellings were used interchangeably and they had no geographic connotation until 1960.

Although at first glance dictionaries may appear static and unchanging, they serve as markers for the fluid shifts in language over time. Because language is dynamic, dictionaries may codify language use but lag behind day-to-day speech and writing. Whisk(e)y is an example of the linguistic power and limitations of dictionaries and provides another layer of complexity to the story.

In 1806, Noah Webster published the first American dictionary, with the first American spelling and definition for “whisky.” His Compendious Dictionary Of the English Language spelled “whisky” without an “e” and simply defined it as “a spirit distilled from grain.” In the 1828 and 1844 editions of An American Dictionary of the English Language, the definition expands to include information on geographic differences in the UK and the US. “In the north of England, [whisky] is given to the spirit drawn from barley. [While] in the United States, whisky is generally distilled from wheat, rye or maiz.” Webster’s dictionary demonstrates that the primary difference between whiskies made in the US and the UK was their agricultural base, not their spelling. However, Webster was a strong proponent of simplifying the spelling of English words and led the effort to Americanize words like “color” and “colour,” “favor” and “favour,” and “center” and “centre.” Webster’s decision to list just one spelling for “whisky” may have been motivated by his desire for a single simplified spelling.

After Noah Webster’s death, the family sold the rights to his dictionary, and in 1890 this resulted in the first edition of Webster’s International Dictionary of the English Language. It was the first dictionary of American English to include both spellings of “whiskey.” Even though both were listed, nothing was said about a geographic preference in spelling. The most noteworthy thing about Webster’s International is how “whiskey” and “whisky” were used in other definitions. The definitions for “bourbon,” “julep,” and “spirit” all used “whisky,” whereas “usquebaugh,” the Gaelic root for “whisky,” was defined as “Irish or Scotch whiskey”—with and e!

Books and newspapers from the mid-19th through the early 20th centuries also demonstrate how Americans used “whiskey” and “whisky” without any consideration for where the spirit came from or of a geographic preference in spelling. Ambrose Bierce, a journalist and contemporary of Mark Twain, published approximately 1,000 satirical definitions of everyday words that were collected into a book called The Devil’s Dictionary. From 1881 to 1906, “whiskey” and “whisky” are used in four definitions. “Whiskey” appears in “Economy,” and “Severalty,” whereas “whisky” was used in “Tope” and “Wheat.” None of those uses carried any geographic connotation. Meanwhile, California newspapers from the 1840s to 1920s and New York state newspapers from 1850 to 1950 repeatedly used both spellings of “whisk(e)y” to describe aged grain spirits made in the US, Ireland, Scotland and Japan.

All of this is significant because of two important events that took place around 1960. The Ngram graph of American English (Figure 2) shows a precipitous drop in the use of “whisky” versus “whiskey” that can only be explained adequately by newspaper style guides. In 1950s the Associated Press, Los Angeles Times and the New York Times all published style guides that gave instructions on how to, among other things, spell “whiskey.” These style guides are important not only because these newspapers had large readerships, but also because other papers, magazines and writers used them as a reference when publishing their own works. The AP Stylebook and LA Times Stylebook use “whiskey,” but allow an exception for “whisky” when referring to Scotch (AP Stylebook) or Scotch and Canadian whisky (LA Times). These two style guides are the first published sources in the US to demonstrate a geographic preference in how “whiskey” was spelled. The appearance of these style guides in the second half of the 20th century mirrors the changing preference in the US for “whiskey,” and the idea that “whisky” (for the most part) refers to non-US aged grain spirits. Whereas it is certain that the AP and LA Times did not create these distinctions, the evidence suggests that they were the first to codify them.

One interesting outlier was the New York Times. From 1950 to 1976 The New York Times Manual of Style required its writers to use “whisky” in all circumstances. However, in 1999, for an unknown reason, the Times reversed that mandate and stipulated instead to use “whiskey,” no matter where it was made. The issue seemed settled until late 2008 when an Internet controversy erupted over the insistence that Scotch whiskey be spelled with an “e.” In February 2009, after a flood of negative feed back from readers about their one-size-fits-all policy, the Times changed their style guide again. This time they adopted the LA Times rule which spells all whiskey with an “e,” except when referring to Scotch or Canadian whisky. As it turns out, these style guides provide the best answer for why the US came to understand “whiskey” as referring to native aged grain spirits whereas “whisky” has come to stand for aged grain spirits made outside the country.

Although the two different spellings of “whiskey” evolved and solidified in the mid-18th century, it is only in the last 50 years that these two spellings have ceased to be interchangeable in the US and imbued with a geographical meaning. The recent controversy and confusion surrounding the use of each spelling of “whiskey” points to something deeper: American English is in the midst of a linguistic shift in spelling and usage of “whisk(e)y.” While some might wish to hew to a past that never existed, the language has continued to march on. Switching between “whiskey” and “whisky” can be a bit cumbersome, however, this shift offers a greater degree of precision and specificity in a global marketplace that eschews linguistic imperialism. n

Editor’s Note: It is the policy of Distiller to use the American spelling whiskey when referring to the substance. The spelling “whisky” is used only when included in a brand name. Your opinions are welcome and we invite you to participate in a discussion on the ADI forum.

(We do not use rhum for rum from French-speaking territories or ron for rum from Spanish-speaking territories. Therefore, do not be confused to see the brand name Ron Burgundy. It’s whiskey.)