All spirits evolve in how they’re made and how they taste. But unlike single-country spirits like bourbon or Scotch whisky, rum evolved in many places and under the influence of numerous spirit-making traditions, including British, French, Spanish, and Portuguese. Two rums made just an island away from each other can be wildly different in taste. Understanding how the many styles of rum came about helps to understand why they taste so different.

What follows is 400 years of rum-making traditions enormously simplified. But knowing key elements of rum’s backstory should make you want to dig deeper into understanding the world’s most diverse spirit.

Primordial Rum

While there is ample evidence that distilled sugarcane spirits predated Caribbean rum, the first distillation of rum as we know it today was undertaken by European colonizers around the 1640s in either Barbados or Martinique — written records were hit-or-miss back then. These colonizers primarily came to the Caribbean to extract precious resources unavailable in their European homelands.

Sugar was the Caribbean’s highest-valued export; everything else was secondary. Unimaginable numbers of enslaved Africans were imported to work in hellishly hot conditions on sugar estates, tilling the fields, harvesting the sugarcane, and boiling sugarcane juice to make crude sugar crystals. The boiling juice acquired a foamy scum known as skimmings, which was removed as waste. Likewise, the coarse sugar crystals were coated with molasses which drained off the cooling crystals and was collected.

Most estates used this sugary production waste to make rum. Skimmings, molasses, and occasionally, juice from rotting sugarcane went into a vat where airborne yeast kicked off fermentation. After a week or more, the resulting wash was twice distilled in crude pot stills.

These first rums, aka kill-devil, guildive, or taffia, were exceedingly rough and crude. No one dreamed of aging or exporting them. Instead, they were given to enslaved workers or sold to the local population. The French polymath Jean Baptiste Labat wrote in 1694, “it is enough for them that this liquor is strong, violent and cheap, it matters little to them that it is harsh and disagreeable.” Aging to smooth off the rum’s rough edges wasn’t a concern, and any casks on hand were usually more valuable for shipping sugar to Europe.

Heavy, Pot-Distilled Rum: The First Style

Luckily, sugar- and rum-making know-how had improved substantially by the early 1700s, and sugar estates started dominating Caribbean island landscapes. Alarmed by competition from inexpensive Caribbean rum, influential French and Spanish spirit merchants pressured their governments to clamp down on it.

Distillation was disallowed or strongly discouraged in colonies like Martinique, Guadeloupe, Haiti, Cuba, and Venezuela for most of the 1700s. (Illicit distillation and rum-running still took place, naturally.) French Caribbean estates that weren’t allowed to distill their molasses instead sold it to New England colonists who (you guessed it) made New England rum with it.

British colonists on islands like Barbados, Jamaica, Grenada, and Antigua had no such constraints and became powerhouses of heavy, pot-distilled rum. Dunder, aka vinasse or lees, was a large part of this era’s mash recipes. A typical mash consisted of dunder, sugar skimmings, and water in a ratio of ⅓ each, and the resulting rum was packed with flavor. Today we might call these rums fermentation forward.

British Caribbean rum exports to Great Britain started in earnest in the early 1700s, much of it aged in excise warehouses alongside U.K. docks. While Barbados was Britain’s first rum-making colony, Jamaica became Britain’s largest rum maker by an overwhelming margin. Jamaica’s flavorful rum found great favor in London and Liverpool, where it competed head-to-head against Indonesian Batavia arrack and French brandy as the most preferred and expensive spirit. One can draw a straight line between the Jamaican rums of the 1700s and many of today’s Jamaican rums, including Hampden Estate, Long Pond, and Worthy Park.

The Industrial Revolution and Competition

The industrial revolution of the 1800s brought massive scale to agricultural processes like sugar and rum making. Steam engines enabled far faster sugarcane crushing than wind, water, or animal power allowed. The vacuum pan began replacing workers who ladled hot juice in boiling houses. Scale ruled the day as a handful of large central sugar factories processed more sugarcane than dozens of small estate sugar mills could. Molasses was plentiful and cheap, and distilleries no longer had to exist alongside sugar mills.

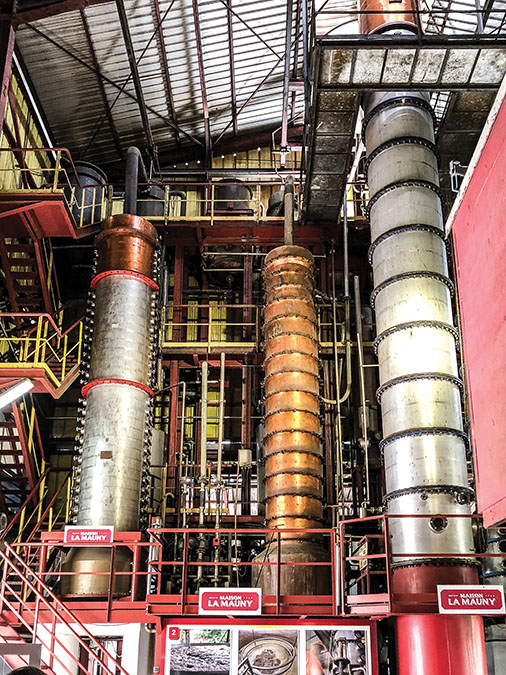

The industrial revolution also brought substantial improvements in distillation scale and efficiency. While the double retort pot still found a permanent home in Caribbean distilleries, continuous distillation was a larger game changer. French inventors like Jean-Baptiste Cellier-Blumenthal, Louis-Charles Derosne, and Armand Savalle, and the Irishman Aeneas Coffey iterated on various column distillation improvements. Their equipment quickly migrated to the East and West Indies, although the vanguard of Britain’s heavy, pot-distilled rum makers resisted continuous distillation for many decades.

The industrial revolution also brought an existential threat to Caribbean sugarcane and rum. Britain’s Royal Navy prevented French Caribbean sugarcane from reaching France during the Napoleonic wars. Napoleon responded by subsidizing research into making sugar from beets, which grew well in Europe. Beet-based sugar soon flooded world markets, causing sugar prices to fall dramatically and severely disrupting the once highly profitable Caribbean sugarcane economy. Many sugar estates consolidated or shut down completely, with Caribbean rum making wounded in the crossfire.

Seeking high tax revenues, France and Spain eventually lifted restrictions on distillation in their Caribbean colonies. With a meager distillation infrastructure at best, French and Spanish Caribbean industrialists purchased the newest distillation technologies; records show column stills in the Caribbean by the 1830s.

The industrial revolution’s alteration of sugar economics and its introduction of continuous distillation set the stage for rum to cleave into several distinct styles.

The Rise of Cane Juice Rum

The first two centuries of Caribbean sugarcane agriculture were entirely focused on sugar profits. Any income from rum was incidental. But when overproduction dropped sugar prices to precipitous lows, many Caribbean estate owners rethought their options. One approach was specialization. Small estates that previously grew sugarcane to process into sugar and rum themselves transitioned to sending their sugarcane to the nearest central sugar factory.

In Martinique, “sugarcane train” tracks surrounded central sugarcane factories. Estates near the tracks delivered their cane to the passing train and collected payment after weighing it at the factory. The molasses from the central factories went to large-scale stand-alone rum distilleries in the major port of St. Pierre. Martinique was the world’s largest rum exporter in 1902 — molasses rum, that is.

However, estates farther from the tracks couldn’t sell sugarcane to the factories, nor could they sell their sugar profitably, as the central factories could sell sugar for much less. Faced with extinction, rural estates gave up on making sugar and used all the cane juice to make rum. Estates could make five times as much rum per hectare of sugarcane using this approach, as 80% of the sugarcane’s fermentable sugars were no longer lost to sugar crystal production. Today we know this cane juice rhum from Martinique and Guadeloupe as rhum agricole. Back then, it was known as rhum d’habitant (“rum of the locals”). Large-scale exports of rhum agricole didn’t start until the 1950s.

Nearly all rhum agricole is made in a Creole column, a particular type of single column. It’s exceedingly rich in terroir and often consumed unaged, similar to blanco tequila. However, aged rhum agricole is highly prized by enthusiasts.

In the past decade, distillers in locales like Grenada, Belize, and Hawaii have also started using cane juice. Not only does it express terroir better than molasses, using local sugarcane keeps their source material costs lower.

Aging-Forward Rum

In Spanish colonies like Cuba and Puerto Rico, as well as former Spanish colonies like the Dominican Republic and Venezuela, large-scale rum making was well underway by the mid-1800s. But rather than making heavy rums, Spanish expats like Facundo Bacardi and Andrés Brugal looked to the delicate brandies of their homeland. This meant less emphasis on flavors originating in fermentation and more focus on aging-derived flavors. We might call such rums aging forward.

Aging-forward rums use a short fermentation and higher rectification in column stills to make a distillate relatively light in congeners. The distillate then undergoes a complex aging and blending regimen to make rum. Some producers macerate the distillate with fruits and nuts to add additional flavors to the final spirit. It’s also not uncommon to taste the influence of sweet wines on some of these rums.

In the early 1900s, brands like Bacardi found a ready market for clear, light rums aged for three years or less, then carbon filtered to remove the color. When public tastes changed to lighter spirits after World War II, brands like Bacardi, Don Q, and Havana Club became household names.

Today’s aging-forward rums are typically a blend of light rum from a multicolumn still and medium-weight rum from a single column or the beer column of a multicolumn still. All are aged for a year or more, primarily in ex-bourbon casks; longer-aged expressions go to fifteen years or more. By volume, aging-forward rums dominate today’s global rum market.

Moving to the Middle: Pot/Column Blends

While the French and Spanish heritage rum-making regions quickly adopted the column still in the 1800s, the British colonies lagged behind. Barbados got its first column still in 1893, and Jamaica held out until the 1950s. Despite their long traditions of heavy, pot-distilled rums, changing consumer tastes and less expensive column distillation made aged pot/column blends inevitable.

Nearly all Barbados rum made today is a pot/column blend, as are the rums from Guyana’s lone producer and Jamaica’s two largest producers. Even Venezuela’s two flagship distilleries utilize pot-distilled rums in their blends for extra depth.

High-Congener Rums

Webster defines adulteration as “[causing] to corrupt, debase, or make impure by the addition of a foreign or inferior substance or element.” It’s a centuries-old practice across all spirit categories. But when it comes to rum, adulteration takes an unusual form. Rather than stretching a high-quality rum with a lesser rum, European blenders encouraged rum makers to make a rum concentrate that only those with an iron palate can drink neat.

To save on import duties, German blenders in the 1880s paid top dollar for the heaviest Jamaican rums and then stretched with neutral spirits, both grain- and grape-based. Some Jamaican distilleries, primarily in the Trelawny Parish, started focusing on making rums with astronomically high congener levels, which became known as “Continental” or “German” rum. Among their tricks were mash recipes using sugarcane acid, dunder, and muck, which is putrefactive bacteria added to the dead (fermented) wash a few days before distillation to induce the creation of more complex esters.

French blenders of the era also sought high-congener rums, albeit from Martinique and Reunion. These French high-congener rums are known as Grand Arôme (“big aroma”) and use some of the same techniques that the Jamaicans use.

High-congener rums are still made for judicious use in rum blending and food flavorings. Distilleries making them include Long Pond, New Yarmouth, and Hampden Estates (Jamaica), Le Galion (Martinique), and Savanna (Reunion). All producers sell it unaged, but some enterprising independent bottlers age it themselves.

Great Strength in Diversity

A sea change in the rum market has taken place in the last 15 years, driven in part by craft cocktail bartenders demanding the same rum styles used in classic recipes. Enthusiasts are willing to pay hundreds of dollars for single-cask releases. Today’s wealth of high-end and unusual expressions was unimaginable five years ago.

This cornucopia of choices is often bewildering to newcomers. Many picture rum as a single spirit, à la bourbon, gin, or Scotch. But rum is a meta-category encompassing many spirits, just like whiskey and brandy. If we recognize bourbon and Scotch as distinct spirits with their own traditions, we should also understand that rum’s many styles, such as Cuban rum, Jamaican rum, and rhum agricole, are also distinct spirits. The only thing that all types of rum share is their common origin in sugarcane.