In our distant history an ancestral distiller wasn’t satisfied with the elixir from his crude still. He no doubt had traces of grain carryover, entrainment, and greasy grain deposits called gunge (a term Americanized into grunge) and possibly patches of copper sulfate (verdigris), a blue-green residue from the reaction of fermented mash to copper.

These defects and high boiling congeners were referred to a “hog tracks” by the farmer-distiller. The desire to remove such impurities and improve the whiskey’s flavor led to the practice of distilling alcohol a second time. The frugal distiller probably experimented with the idea by using his only still for both distillations. The initial distillation separated the alcohol from the mash (or wash if you are from the other side of the big pond) and the second distillation refined the distillate. The effect of a second distillation was surely dramatic. However using one still for both operations proved, no doubt, cumbersome and led to the development of a secondary distilling apparatus called a doubler. The doubler eventually led to subsequent methods of the rectifying practices called the continuous doubler and the thumper.

So how did the equipment evolve?

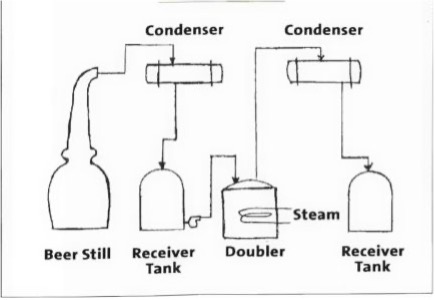

The Doubler

During the beer still distillation the condensed alcohol is collected in a receiver tank. When enough distillate is collected to make an efficient charge it is transferred into the doubler at ambient temperature. The doubler is a batch pot still. It holds liquid, is heated by direct flame or a steam coil at the floor of the vessel and has a worm or condenser to convert its vapors back into a liquid. Using the same principle as the beer still (alcohol boils at a lower temperature than water) the low temperature ethanols are distilled and recovered first with others to follow until all desirable product is recovered. The distiller then decides to: 1) distill all the alcohol into the final product, 2) divert the low wines to the beer still receiver tank for redistillation or to the beer still as reflux, or 3) simply throw away the low wine with the spent lees. In todays processes the alcohol comes off the beer still at between 90–125° proof and from the doubler at 135–140° proof.

The Continuous Doubler

The continuous doubler is basically the same with one exception. The condensed high-wine from the beer still by-passes the receiver tank and is sent directly to the doubler for redistillation. This process is continuous and reduces the distillation time. The residual in the doubler is either sent back to the beer still as reflux at approximately 25° proof or emptied every few days to prevent build-up of acids and other undesirables.

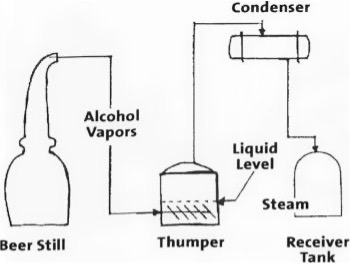

The Thumper

The thumper is a continuous operation and the equipment is similar to the doubler but without the heating coil. A sparger is located near the floor of the thumper and a liquid level of 12–24 inches is maintained. The uncondensed vapors from the beer still are discharged via the sparger below the liquid level. When the hot vapors come into contact with the slightly cooler liquid inside the thumper the alcohol condenses and then flashes back into a vapor. This flashing action creates an intense reaction that generates a loud noise similar to a water hammer. The thumper gleans its moniker from this noisy interchange. As the vapors hit the thumper they are condensed into the final product.