“Where the English went, they built a house;

where the Germans went, they built a barn;

where the Scots-Irish went, they built a whiskey still.”

— An old Appalachian proverb

With the rise of artisan distillation in the US, most producers have decided to focus on more typical spirits such as vodka, gin and rum or more specialized spirits such as eau de vie or malt whiskey. A few other distillers however are choosing to trade on a bit of legendary history and produce moonshine.

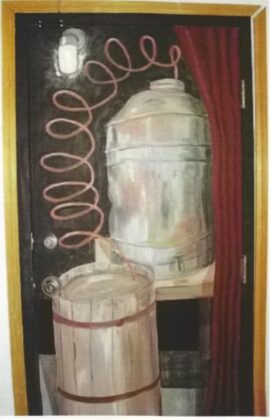

Moonshine, a term that originated as a verb, was first used in Britain where it referred to employment or other activities that took place late at night. In the US however, it has always been associated with illegal liquor and has been known under many other colloquial names such as white lightning, popskull, corn liquor, rotgut, panthers breath or more simply, shine.

The practice of moonshining is inextricably tied to US history in numerous ways. After the American Revolution the United States was strapped financially due to fighting a long war. In an attempt to address this problem, a federal tax was levied on spirits. This did not sit well with the newly liberated people who had just concluded a war where the purpose was to eliminate British taxation. This gave rise to the practice of making distilled spirits clandestinely to circumvent taxation.

Early on, this practice was a method of survival, not extra profit. If farmers experienced a bad crop year, they could use their corn for making whiskey. Given that this was a practice of subsistence, the payment of tax on this product might mean they would be unable to feed their families.

Thus began the contentious relationship with federal agents who often were attacked when they tried to collect the tax.

In 1794, things finally came to a head with the Whiskey Rebellion. A group of several hundred managed to overtake the city of Pittsburgh, PA. In reaction, George Washington dispatched 13,000 militiamen to take back the city and jail the leaders. This incident served as the first major test of authority for the fledgling government.

The battles between the government and moonshiners continued to rage on. In the 1860s the government attempted to collect more excise taxes as an attempt to fund the Civil War. In response, a number of elements joined together with the moonshiners, including Ku Klux Klansmen in an attempt to fight back. The new alliances lead to more brutality and incidents of intimidation of any local people who might reveal stills as well as agents and their families. The Temperance Movement then added these happenings to their arsenal on the march towards prohibition.

The states began to prohibit the sales of alcohol in the early 1900s and then complete national prohibition was established in 1920. Prohibition’s enactment provided the best possible scenario for moonshiners. With no legal means of obtaining alcohol, demand grew exponentially with which the moonshiners could not keep up. In response, the producers began using cheaper ingredients such as sugar and even watering down their whiskey.

A large network of distribution was established with the assistance of organized crime. To supply the illegal spirits to this network, young men in rural areas close to the still operations delivered moonshine in highly modified, high performance cars. The temptation was irresistible to these men as the income they could make in a single night was greater that a couple of months of honest work. What started as a transportation method for moonshine was what gave birth to stock car racing which formalized into today’s NASCAR.

With the appeal of prohibition in 1933, the demand for moonshine declined rapidly, returning the practice mostly back to areas concentrated in the Appalachian region of the East Coast. Even today, there is illegal production of moonshine in these regions with operations located in northern Georgia, western South and North Carolina and eastern Tennessee. Due to the independent and strong willed character shared by most Americans it is felt by most historians that moonshine will always be around in one form or another.

Today there are a few who have decided to produce moonshine legally. Not surprisingly, these individuals are located in the same regions of the East Coast where the illegal version is still made. In the search of some of these producers my father and I set out to learn how they are making the spirits and what market exists for the legal versions. Being that my office is in Bridgeport, West Virginia we were at a perfect starting point for this trek.

I went into this journey expecting to see that all the producers we visited were doing something similar…. boy was I wrong!

West Virginia Distilling

Granville, West Virginia

www.mountainmoonshine.com

Located about 45 miles from my office in North Central West Virginia, West Virginia Distilling is located in a suburb of Morgantown, home to West Virginia University and is only 8 miles from the Pennsylvania border. The owner and operator of West Virginias first legal distillery is Peyton Fireman, a lawyer and childhood acquaintance of mine.

Beginning in 1998, Peyton started out trying to get access to regional illegal moonshine producers to learn how to make moonshine, but did not have much success. What he found was that the younger generation that he expected to have had the practice of making moonshine handed down to them found that it was far more profitable to grow marijuana than it was to make moonshine. So, he had to learn on his own by reading distilling texts and asking questions of the few micro distillers that existed at the time.

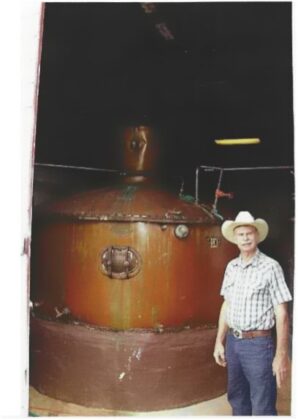

This small distillery is housed in a former transmission shop. Peyton is a very resourceful tinkerer. With the help of a local engineer, he made his stills out of old 40 gallon electric water heaters with columns made from lengths of copper pipe and condensers made from copper coils, all sourced from local home builder supply outlets. He now uses these stills to re-distill head and tail cuts and instead undertakes the main distillation in the equipment pictured above. His total investment to date has only been $40,000! Three times a year, Peyton puts his legal practice on hold and becomes a distiller.

Peyton makes only one distillate but it is presented in two different ways. One, Mountain Moonshine is a colorless spirit that is bottled immediately after final distillation. The other, Old Oak Spirit Whiskey, is mellowed by soaking toasted oak wood chips in it for 30 days.

Peyton introduces corn grits into the home built still which also serves as his mash cooker and fermenter. It is heated by a waste oil fired hot water boiler that supplies hot water to external coils that he has mounted underneath the vessel. He accomplishes starch conversion by allowing the mash to rest heated for a couple of hours and then through the addition of enzymes.

Once mashing is over, he attaches an external chilling loop to the vessel and cools the mash down to fermentation temperature via internal coils. Once cooled, he adds brewing yeast to the mash and allows it to ferment for 4 to 6 days. When fermentation is over, he then heats up the vessel again and distills the alcohol from the wash.

Technically, Peyton is not producing a traditional moonshine but rather a spirit whiskey. His corn mash derived spirit makes up only 20% of his product. To produce the final spirit he blends his distillate with neutral grain spirits. His products are released to market at 80 and 100 proof.

When asked if he feels there is a market for his product, Peyton defers to a quotation that was printed in a recent article published in a paper. Monntie Pavon, the owner of a local bar called Levels, stated “people like the idea of drinking moonshine. They see it up on the shelf and say: ‘You sell moonshine? I thought it was illegal.’ ” This attention getting feature of the product certainly provides advantages when trying to induce people to try it. Presently, West Virginia Distilling sells a little over 1,000 bottles of Mountain Moonshine and Old Oak Spirit Whiskey per year.

Isaiah Morgan Distillery

Summersville, WV

www.kirkwood-wine.com/isaiahmorgan.html

My father and I travelled due South of Bridgeport WV for about 1.5 hours to Summersville, WV in southern WV for our next stop on the legal moonshine trail. Summersville is a small but booming town that is becoming a sporting mecca due to its close proximity to man incredible recreational opportunities. The area serves as a gateway to the New River, one of the oldest rivers in the world and has almost 900 deep gorges and whitewater rafting that rivals Colorado and other western states with the river’s class 4 and 5 rapids. The New River Bridge, the second longest single span bridge in the world, is the site of Bridge Day, the largest extreme sports event in the world. The area also attracts mountain bikers, rock climbers and fishermen.

The Isaiah Morgan Distillery is located on the site of the Kirkwood Winery which was established in 1992 by the late Rodney Facemire. Unlike WV Distilling, this location is tucked into a quiet mountain valley that makes it easy t picture that moonshine has been produced in th! region before!

We were met by distiller Shirley Morgan, operator of the nations smallest licensed still with a maximum volume of 50 gallons:

Shirley truly produces his moonshine, Southern Moon, the way it was done in this area for a long time. Instead of mashing milled corn, the raw corn is placed in straining bags and soaked in hot water. The bags are removed after sufficient soaking and cane sugar is added to the liquid left behind. For a still charge of 50 gallons he uses 5 pounds of corn and 100 pounds of sugar. Shirley told us that this practice comes from way back in time where the old timers couldn’t mill corn so they dissolved the husks with lye before soaking the kernels in hot water. No, Shirley does NOT use lye!

The distillery ferments its wash in a group of reclaimed plastic barrels that are connected by a draining manifold that supplies the still:

Shirley charges the still with 50 gallons of wash and conducts a double distillation with the final spirit yield of 7 to 8 gallons at 176 proof. The liquor is then diluted using filtered well water to 80 proof and bottled.

Rodney Facemire can be credited with establishing the classification “mini-distillery” in WV. He managed to get a bill sponsored and passed that created the legal class of alcohol distillers, designated “mini-distillery”, which are defined as “where, in any year, twenty thousand gallons or less of alcoholic liquor is manufactured with no less than twenty-five percent of raw products being produced by the owner of the mini-distillery on the premises of that establishment, and no more than twenty-five percent of raw products originating from any source outside this state”. Additionally, unlike Wisconsin and some other states, the law allows mini-distilleries permission to allow on-site tasting and on-site retail sales of the liquor they produce. It also allows the mini-distillery to advertise off-site. Being that WV Distilling was established prior to this law, they are the only distillery that is exempt from the ingredient sourcing provision.

In addition to Southern Moon Corn Liquor, Shirley also produces a grappa made from concord grapes, and a rye whiskey. He plans to release a barrel aged version of a whiskey made from rye, malt and corn in 2010. Recently he has begun experimenting with making rum from sorghum molasses that is pressed from cane that is grown in Northern WV.

Belmont Farm Distillery

Culpeper, VA

www.virginiamoonshine.com

After visiting the Isaiah Morgan Distillery, our trek took us into Southern Virginia about 3 hours south east of Summersville, WV to Culpeper, Virginia.

Culpeper is a very quiet area of rolling hills with many farms and several well regarded wineries. The area’s quiet appearance belies its close proximity to Washington, DC and Charlottesville, VA.

Chuck Miller, owner and distiller, is a consummate showman and quite a character. He opened up his distillery to us which is located in a large converted barn on his farm where he grows all the corn, barley and wheat that goes into his products. If you are a viewer of the History Channel or/and the National Geographic Channel you may have seen him in segments that visited distilleries.

Chuck produces two products, Virginia Lightning (100 proof) and Kopper Kettle Virginia Whisky (86 proof). He also sells a version of Virginia Lightning in Japan but its proof is reduced to 80 to cater to Japanese tastes. Virginia Lightning is made only from corn whereas Kopper Kettle Virginia Whiskey is produced from corn, barley and wheat and is twice distilled just as Virginia Lightning is. Unlike Virginia Lightning, which is bottled just after distillation, Kopper Kettle Virginia Whiskey undergoes two stages of wood aging. The first stage undertaken by exposure to oak and apple wood chips in a large converted stainless steel dairy tank:

After sufficient exposure to the wood in the above tank, it is moved to charred barrels to age for an additional two years before being filtered and bottled. He now sells 4,000 cases per year of his combined product offerings.

Belmont Farm Distillery’s equipment is a combination of history and modern. His still, built in 1933, is a mammoth sight to behold and has a capacity of 2,000 gallons:

How Chuck acquired this still is a story in and of itself. It originally was located in New Jersey where it was legally operated until 1962. The still then was operated illegally until the late 70 s when the operation was discovered and shut down by the federal authorities. Just shortly after this, Chuck was beginning to investigate starting his distillery. In a conversation with federal regulators he asked where he might acquire a still for his operation. The agent mentioned that he knew of the still in New Jersey. Shortly thereafter, Chuck negotiated a purchase price and he relocated the still to his farm in Culpeper. Chuck then installed the rest of his equipment and filed for his federal permit in 1980.

Standing in stark contrast to his museum piece still is his elaborate water treatment system that he uses to make process water from his on-site well. Installed on a wall opposite the still room are multi stage sediment filtration units and a high capacity deionization unit as well as a reverse osmosis system.

When we were leaving the farm, we notice the truck pictured below tucked away in a pole barn the property:

If you look closely at the windshield you can see bullet holes. We asked Chuck what had happened to this truck. Chuck said it was owned by his grandfather and that it was used to deliver supplies to the still location and for moving moonshine. Unfortunately one day his moonshining career ended in this truck when he was caught by revenuers. The bullet holes are an indication that he was not inclined to stop initially!

We had intended to continue on to North Carolina to visit Piedmont Distillers, the producers of Catdaddy Carolina Moonshine and the recently released Junior Johnson’s Midnight Moon, but advance calls to them revealed they were too busy to meet with us. That was unfortunate because had we visited them we would have made a complete sweep of mid-Atlantic and southern producers of legal moonshine and moonshine inspired products.

In addition to those covered in this article, there are some additional producers that I am aware of:

Tuthilltown Spirits Distillery

Gardiner, New York • www.tuthilltown.com

Old Gristmill Authentic American Corn Whiskey

Woodstone Creek — Cincinnati, Ohio