Malting day at Highland Park Distillery, Orkney, means more than just the scent of toasting grain in the air. There’s a smoky edge from peat burning in the kiln, which is a local fuel here that you’ll taste in the whisky. It’s a throwback to when grain was malted and dried for distilling in Scotland and Ireland using peat as the heat source, not wood, gas, oil, or electricity. On the blustery winter day I visited Highland Park, someone was out cutting peat on Hobbistor Moor for the distillery.

Malting day at Highland Park Distillery, Orkney, means more than just the scent of toasting grain in the air. There’s a smoky edge from peat burning in the kiln, which is a local fuel here that you’ll taste in the whisky. It’s a throwback to when grain was malted and dried for distilling in Scotland and Ireland using peat as the heat source, not wood, gas, oil, or electricity. On the blustery winter day I visited Highland Park, someone was out cutting peat on Hobbistor Moor for the distillery.

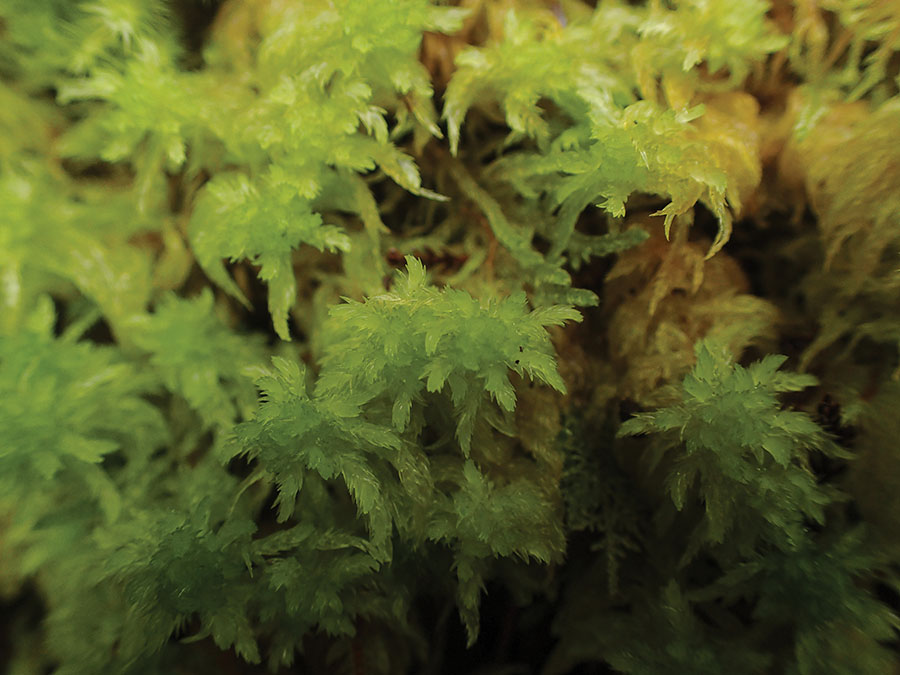

Slowly laid down over hundreds of years and matured over thousands, peat is a dense fibrous soil formed from remnants of plant material compressed in the acidic, wet conditions of a peat bog. Peat from different regions is composed of different assemblages of partially decomposed vegetation. There is always sphagnum moss (Sphagnum species), the botanical architect of peat bogs, in peat. Orkney peat is considered to contain more heather (Calluna vulgaris) than peat from Islay, another Scottish island famous for peaty whisky. These differences are how peaty flavor brings a sense of place.

There are at least 44 compounds in peat smoke, most of which are phenols and furan derivatives. Phenols are used as a marker of peatiness, although this measure doesn’t capture the full range of peat-smoked flavor. Orkney peat, for example, produces less phenol than Islay peat. Lightly peated whisky contains phenols of 1–5 parts per million (ppm), and heavily peated whiskies can reach well over 50 ppm. Lignin, a structural material in plants, produces guaiacol when burned, which is particularly associated with smoky flavor.

Peat bogs have been recognized as ecosystems that sequester vast amounts of carbon. Even though peatlands cover only 3% of the world’s surface, they contain up to 44% of all carbon stored in soil. But peat bogs aren’t just a repository for carbon, they are places with ecological and cultural value, and they are found around the world.

For those who haven’t visited peatlands, Dr. Janelle Baker, associate professor at Athabasca University and long-term collaborator with Bigstone Cree Nation, gives a description that evokes the sense of being there:

“Muskeg is a term widely used in Canada and is an anglicized spelling of the nehiwewin (Cree) word maskek that describes the peat bogs of the subarctic boreal forest. Muskeg smells like earthy tea and is mossy, deep, and spongy. I find muskeg to be magical. I mean, pitcher plants and sundews grow there! So many unique mosses, medicinal plants, orchids, and berries are in the muskeg — it’s like a tapestry, and when you get closer these remarkable species pop out at you. If you avoid these places because they are watery and difficult to pass, you never see the bizarre and remarkable species flourishing there. I think this is a large part of the problem of deforestation of the boreal and loss of peat bogs — that people don’t spend time in these places, and so they don’t appreciate the very particular and irreplaceable landscapes that they are. Peat bogs take centuries to form — we can’t grow or farm them!”

Peat use by distilleries has been smaller than that by other industries. However, a ban on horticultural products containing peat is set to begin in the UK in 2027 and come into full force in 2030. Ireland’s phasing out of peat-fueled power stations has also reduced commercial peat use. Against this backdrop, peat consumed by distilleries in whisky making is becoming more notable. Getting peat smoke flavor into grain more efficiently can reduce the amount of peat consumed. Methods of maximizing flavor extracted from peat include recycling smoke so that it passes through grain repeatedly, and misting grain with water, which increases adherence of smoky compounds.

Sales of peated whiskies show that smoky flavors are popular in stand-alone spirits and make distinctive ingredients in cocktails. Smoke works well as a counterbalance to sweet flavor. It also adds richness and depth that is typically created over time as spirits age. Eco-conscious distillers and consumers are showing an appetite for smoky flavor from other sources, whetted, in part, by awareness of the need to keep peat in the ground. The good news is that curious distillers have a wide world of smokiness to explore.

Non-Peat Sources of Smoky Flavors

Peat isn’t the only fuel that can increase the phenol content of malted grain, and grain isn’t the only fermentable that can be infused with smoke. Corn can be smoke-treated to make smoky bourbon. Mezcal’s distinctive smoky taste is created by roasting agave before it is fermented. The same system that fans peat smoke across malting grain can use other smoky fuels. Regional cooking including barbecuing and smoking meat and fish offers an established repertoire of smoky flavor using wood from different trees.

While fruit trees such as cherry and apple grown in orchards are international in their use for smoking food, wild mesquite (Prosopsis species) is best known in the American Southwest, where it is used for its earthy taste in barbecuing. In the Northeast, sugar maple (Acer saccarum) is a sweet-tasting and abundant tree that yields flavored smoke. As with peat, the release of flavor from woodsmoke into grain can be maximized by recirculating smoke and wetting grain.

In contrast to woodsmoke’s slow burn, hay smoke is quick. If woodsmoke is evocative of campfires, hay smoke is a softer sense of orchards where the grass is allowed to grow long in autumn. Hay smoke has appeared on every course in restaurants, from light bites of hay-smoked quail eggs and mozzarella, to hay-smoked fillets of fish and gnocchi, to desserts of parfait infused with toasted hay. Food-grade hay has to be grass that has grown free of pesticides.

While hay, peat, and wood are burned to release smoke, capturing it in the source of fermentable sugars isn’t the only way to introduce smoky flavor into spirits. Hot smoking and cold smoking can be used on a variety of ingredients. In hot smoking, the ingredient is cooked and infused with smoky flavor simultaneously. In cold smoking, the ingredient is not heated above 86°, so while it absorbs smoky flavor, it isn’t cooked in the process.

Fig (Ficus carica) offers two methods to capture smoke. Succulent fig fruits are a damp surface for smoke to adhere to. Hot smoking them changes the sweetness to a richer caramelized flavor. Smoked figs need additional drying to have a shelf life for use outside of the fruiting season. Fig leaves have a honey-spiced flavor. While fig fruits are readily available for purchase, fig leaves are difficult to source even though they have a long track record of being used as an aromatic wrapping that enhances food. However, one fig tree can yield an abundance of leaves, even if it is reluctant to fruit. With large surface-area-to-volume ratio, and lower water content than fig fruits, fig leaves can be dehydrated by smoking. There is a long season for collecting fig leaves, running from early summer through to leaf drop in fall. Dehydrated fig leaves store well when kept in an airtight container. Neither leaves nor fruits are sold smoked, so these are ingredients that need to be processed on-site using a smoker for the desired flavor profile.

Poblano pepper (Capsicum annum) is sold in two smoked forms. Earthy and smoky, like mesquite-smoked malted grain, ancho chili is a smoked and dried, nearly ripe poblano pepper. This same pepper, processed by smoking and drying when fully ripe and a little sweeter, is the more chocolatey-tasting mulato pepper. Holding very little heat, these two forms of chili can be used by distillers to infuse flavor without chili heat when left to soak in spirit.

Used in amaro, rhubarb root is available as a dried ingredient. It tastes bitter and is credited as a botanical that brings smoky flavor. Rather than being intrinsically smoky tasting, it picks up smoky flavor during processing as it is dried over fire. Its market availability stems from its popular use in traditional Chinese medicine that refers to both Rheum officinale and Rheum palmatum as da huang. Rhubarb root is underexploited as a flavoring in drinks despite being recognized as a food flavoring by the FDA.

Tea straddles both aspects of being fuel for smoke and being infused with smoky flavor. In Sichuan cuisine, tea-smoked duck is a well-known dish. Black tea is heated to give off smoke while the duck is also being cooked. Lapsang souchong is black tea that is smoked over pinewood and picks up a resinous smoky flavor. Lapsang souchong is a convenient source of smoky flavor because it is readily available.

Even though tobacco might seem an obvious candidate for smoky flavor, it isn’t suitable for use in drinks due to its nicotine content. Drinking tobacco-infused spirit would deliver far more nicotine than smoking the same amount of tobacco. Relatively small quantities of tobacco-infused alcohol could deliver a fatal dose of nicotine. For this reason, its use in drinks is prohibited.

Because of the time it takes to make, peat is functionally a nonrenewable resource. Fortunately, distillers can get smoky flavors from other sources. Traditional food processing techniques using smoking as a preservative and flavoring process and contemporary restaurant usage of smoky flavors demonstrate that there’s more to the realm of smoky spirits than peated whisky or mezcal.