Amaro has a larger stateside presence than ever before. Not only are we importing a greater array of amari from Italy, American craft producers have also been trying their hands at making domestic expressions. From coast to coast there are dozens of quality amari being made by American producers, while bars dedicated to the bitter and herbal complexities of amaro have emerged alongside them.

Consider Campari — and for that matter even its softer sibling, Aperol, and its now-universal Aperol Spritz — the gateway drug. Patient zero. You can thank the Negroni and the Boulevardier, and craft cocktails on the whole, for amaro’s emergence from the shadows. Anything that provided tantalized, thirsty patrons with a bitter tinge helped move the needle that much further toward the light — or in this case, the dark. The dark, the bitter, the bracing. Amaro, that’s amore.

“The American consumer is still just dipping their toes into the pool regarding amari,” says Sother Teague, who, as the beverage director of Manhattan bitters bar Amor y Amargo, is a guy who knows a thing or two about the subject. “My position is unique and typically draws a more adventurous imbiber, but overall I’m seeing a definite lean towards bolder more assertive flavors. Not just at Amor y Amargo where it’s our bread and butter but at all the properties I oversee.”

Amaro’s Rising Popularity

As bitter-forward cocktails took root, early American producers pounded the pavement with consumer education to both introduce amaro and reinforce consumer interest. “When I first started to introduce our herbal liqueurs in the market, we focused a lot on consumer education, as amari were not so popular,” says Francesco Amodeo, president of Washington, D.C.’s Don Ciccio & Figli. “Now, everyone that comes in is aware of the category and ready to explore what we do. Many more people are open to tasting all of the bitter products we produce these days, and a big part of why they are more accustomed to bitterness is the application through cocktails.”

Behind the bar, Teague has had a direct hand in the matter with the programs he runs but has seen it elsewhere as well. “Amari is becoming more and more mainstream as guests seek out more ‘interesting’ or ‘rare’ flavors,” he says. “At Amor y Amargo, one of the top requests I get is guests asking for ‘something I’ve never tried before.’ That’s telling.”

As Teague mentions, though, he has an inside track in the world of amaro, and that doesn’t mean the category has become fully mainstream. Those gateway drugs still dominate, but more and more consumers are becoming conversant on the subject and willing to dabble.

“While the average consumer might skip over the section containing bitter liqueurs in the bottle shop, we get more people asking about our three types of amari in our cocktail room than any of our other two dozen spirits and liqueurs, so the interest is clearly there,” says Dan Oskey, founder of Tattersall Distilling. “The audience just needs to feel comfortable enough to ask the question, and on the flip side, we need to always be willing and ready to give them a taste and share our knowledge.”

Skip Tognetti of Letterpress Distilling concurs. “I have definitely seen an increase in interest and understanding of the category,” he says. “It’s still a small but focused group, but more people are learning what amaro is. I’d say one in ten people who walk into my tasting room — who aren’t there specifically for amaro — know what it is. But five years ago, that number would likely have been closer to one in twenty. And as mentioned, more and more, I see people coming in or calling specifically looking for our amaro as well.”

The producers mentioned thus far represent only a few of the many who have thrown their hat into the amaro ring. From St. Agrestis in New York to Amaro Angeleno in California, and just about everywhere sandwiched in between, amaro is being made all across the country.

“When we first launched Amaro delle Sirene in 2014, you could only find a handful of American amari,” Amodeo says. “Today, it’s almost hard to count!”

Teague pinpoints a few others in particular that he’s fond of: Breckenridge Bitters “is outstanding for its mountain herb amaro. It’s spicy and dry and reminds me of some of my favorite Italian makers;” Kansas City’s J. Reiger Co. for its coffee amaro, “It’s an outstanding drink as it is and works easily into cocktails;” and the red bitter from Capitoline in Washington, D.C., “Tiber features great notes of grapefruit peel and hibiscus for when you want a Negroni or Americano variation.” (With Don Ciccio and Capitoline, along with Founding Spirits, the nation’s capital has emerged as one of the nation’s bitters capitals as well. Blame it on the politics?)

What is American Amaro?

Clearly there’s an abundance of American amari. But what is it? Have any styles or trends emerged to define an American amaro beyond the fact that, well, it’s an amaro made in America?

“A common string across most American amari is that we’re all trying to reverse engineer some of the flavors of traditional amari using the botanicals available to us and at the same time bringing something unique to the category,” says Aaron Selya, head distiller at Philadelphia Distilling and creator of its VIGO Amaro. “That’s similar to what you see in many American craft spirits based on older traditions. We are unencumbered by the rules and traditions of the category and the place they come from. It seems to me that we will see American amari expand the breadth of the style.”

Selya has been working on his amaro since before he even began with Philadelphia Distilling in 2015, and has spent the past four years dialing it in until it was ready for the spotlight. “We live by the motto of ‘no wine before it’s time,’ or in other words, until we love the spirit, packaging and brand story, we will not release any product,” says Andrew Auwerda, founder of Philadelphia Distilling. It’s a lesson that’s been learned the hard way time and time again by producers across the country — the first impression counts. So whether you’re basing a new product on an old tradition or diverging entirely from former standards, measure twice and cut once, as they say.

“The fascinating and frustrating thing about the category is that there are no rules to guide either makers or consumers,” Teague explains. “As long as the finished product has integrity, I’m interested in giving it a try and looking for a space for it on my backbar. Compare the category to bourbon, where there are laws in place that dictate how it’s made, meaning that you can compare one bourbon to another objectively, apples to apples. No such guidelines exist with amari, so the comparison is often apples to carburetors.”

In the case of Don Ciccio & Figli, Amodeo has based his company’s products directly on century-old Amalfi Coast recipes from his grandfather. “I was able to retrieve my grandfather’s recipe book, which holds about 45 different products spanning aperitivo, cordials and amari,” he says. “With centuries of production experience behind us, we decided to base our company concept on revival.”

To Teague’s point, when producers are making products in different ways and for different applications, it’s difficult to pinpoint specific styles or standards. “I haven’t seen a coalescence of styles, as every American amaro I’ve seen has been wildly different than what my benchmark is,” says Douglas Margerum of Margerum Wine Company. “I do not see anyone else following any tradition. That said, for our Margerum Amaro, it’s wine-based and has a lower alcohol than my references, which are brands such as Ramazzotti, Meletti, Averna and Jelínek. It could be said that the Margerum is more a combo pack of vermouth and amaro, which is why it works so well in cocktails.”

At Tattersall, Oskey offers his own blend of tradition with an American touch. “Tattersall’s amaro relies on traditional roots, herbs, spices and citrus but then brings in a more American trademark of sarsaparilla, which brings to mind the flavor of root beer,” he says. “That kind of unique approach is what we’re seeing a lot more of lately, and distillers are getting more experimental, using tropical fruits as well as locally sourced herbs.”

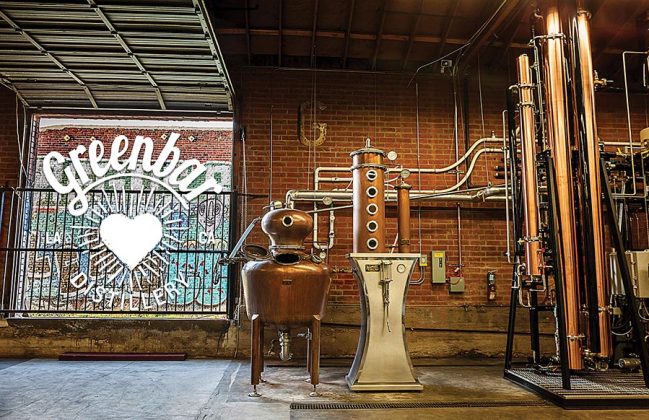

As for that latter point, it’s one of the keys for Greenbar Distillery with its Grand Poppy Amaro. “With Greenbar Poppy, we try to capture California through its indigenous and farmed produce, including our star ingredient, the California golden poppy — a pretty but very bitter flower,” says Melkon Khosrovian, co-founder and spirits maker.

Perhaps all of this blending of new and old, tradition and innovation, is what actually defines the emerging category. “The American or domestic amaro category blends both local and global traditions,” Amodeo offers. “American companies that use foraged ingredients are taking a page out of the old ways book of amaro making with a more modern touch, thanks to technology and manufacturing equipment.”

To Mix or to Sip

There’s no doubt that cocktails have driven interest in the category on the whole. But are producers making their wares with mixologists in mind, or for the savvy sipper? Why not both?

“What I love about amari is that they are very versatile, that is the reason why we produce them in a way that the consumer can either sip them neat or blend them into a cocktail,” Amodeo says.

Still, for many producers, putting cocktails out of the back of their minds and focusing on core flavors is more important during planning and production. “We produced VIGO with consumption on its own being our primary driver,” Selya says. “We wanted to make an amaro that people would drink neat after dinner. The fact that it works so well in so many different cocktails is a wonderful bonus.”

As with Selya, Margerum’s motivation wasn’t in cocktails, though he continues to hear from bartenders and consumers who use his product as such. “Most of our sales are for use in cocktails, though I expected it to be consumed neat after dinner as a digestive,” he says. “That it works so well in cocktails is just circumstance.”

At Tattersall, starting with the right stand-alone flavor is the most important step. “Then we’ll start mixing it into drinks and adjust from there,” Oskey says. “Those secondary adjustments are generally related to proof and sweetness, but not all the time. While some more modern amari are dominated by a single flavor, I personally don’t like one botanical to overwhelm the palate. For me the flavors need to complement each other and play more like a symphony rather than a rock band.”

Tognetti has seen other American amari pushing for cocktail applications first and foremost, but he was always personally opting for a digestivo, something that reminded him of visiting family in Rome when he was growing up. “I specifically approached my amaro as something that I wanted to be delicious on its own as a digestivo first — this was very important to me,” he says. “When I built my amaro, I built it as an amaro, not as a cocktail ingredient. Still, I knew that if I built it well — if it was balanced and tasty and well made — then it would naturally work well in cocktails.”

Even for all of the producers who have said they’re prioritizing stand-alone flavor, there’s an implicit understanding that the result would then be deployable in the latest craft concoction from the trendy bar down the street. Other producers simply start with more of an explicit cocktail focus up front.

“We make all of our spirits and bitters primarily with cocktails in mind,” Khosrovian says. “Our goal is to empower everyone to be able to make rich, complex drinks without having to mix six to eight ingredients together. Our solution is to make very complex spirits that only need two to four ingredients to produce satisfying cocktails.”

Also in California is Lo-Fi Aperitifs, which has brought in expertise from the wine world with Ernest & Julio Gallo Winery, as well as from distillation and brand creation via Steven Grasse of Quaker City Mercantile, and then buoyed that by going directly behind the bar for inspiration. Specifically, they tapped their now brand ambassador Claire Sprouse, known across the San Francisco bar scene from stints at ABV, Rickhouse and beyond, for input on what bartenders were looking for in terms of flavor profiles.

Maybe whether to mix or to sip isn’t the question then. Make a quality product, let it stand for itself, but let the consumers decide why they like it and how they plan on using it. It’s gotten American amaro this far, and we’ve only just begun.