Coffee-infused spirits have been a bar staple for decades. Now, some spirits brands are venturing into the taste of tea.

Expanding from its native range spanning the Eastern Himalayas to Southeast Asia, tea has become a touchstone for cultures around the world. Walking through Shanghai, you can see displays with blocks of pressed pu-erh tea worth as much as a house. In a Japanese tea ceremony, choreographed movements transcend preparing a drink to cultivate a state of mind. In Turkey, tea drinking is social currency as it lubricates meetings and chats. Tea became a symbol of independence at the Boston Tea Party. On a global scale, the only drink consumed more than tea is water. On any day, more than half of Americans will drink tea, and most tea consumption in the USA is in the form of iced tea. Tea can also be spotted on bar menus as a cocktail ingredient.

Common Types of Tea

Tea is a familiar ingredient with a range of guises. One species of plant — Camellia sinensis — offers myriad flavors due to the influence of growth environment, timing and method of harvest, and processing. Tea trees are covered in flat, glossy leaves, but if you look closely, new leaves in bud and just emerging are furled and downy. These buds and new leaves are picked for white tea. After drying, they remain distinct from mature tea leaves, with a fine layer of down still visible on them. Green tea is made from buds and leaves up to two or three internodes below the bud. Leaves are dried whole for both white tea and green tea. After drying, they may be cut, or in the case of matcha, powdered. Processing of white and green tea removes water with minimal change to the chemical composition of the leaf.

Oolong, black, and pu-erh tea are handled differently during the drying process to manipulate and change chemicals present in the leaves at the time of picking. Oolong tea is withered, i.e., allowed to partially but not completely dry. Tumbling the withered leaves provides enough mechanical damage to break cell walls and allow the ingress of oxygen. When the desired degree of oxidation is reached, the leaves are dried in high heat, halting the process of oxidation. Oolong tea is never fully oxidized and can vary in degree of oxidation from eight to 85 percent. Oolong tea’s characteristic furled ball shape is achieved by interspersing the final drying with shaking the leaves in a circular motion. Some Oolong teas are also roasted or toasted, further changing their flavor.

Black tea is fully oxidized. For loose leaf black tea, after young leaves are picked they are withered before being crushed in rollers. Breaking the cell walls in this manner maximizes oxidation of the cell contents. Then, fully oxidized leaves are dried. Tea used in tea bags is treated slightly differently. Instead of being rolled, the withered leaves are treated with the cut tear curl method (CTC) whereby leaves are cut and torn apart to encourage oxidation before being dried.

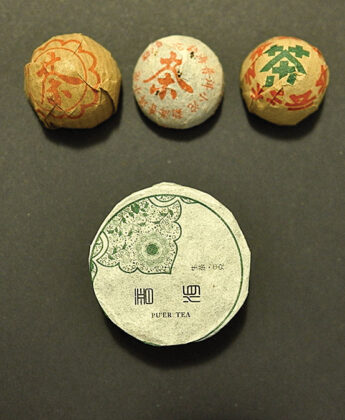

Pu-erh tea is characterized by aging to allow the development of flavor. In the past, it was a process that occurred naturally as blocks of tea were exposed to rain, heat, and the sweat of horses as they were transported on the Tea Horse Road through the mountains of southwestern China. In the 1970s, this natural aging was mimicked and expedited using heap-fermentation of leaves. Much as aged whiskey and rum can be considered rare enough for auction and achieve high prices, so can pu-erh tea, with winning bids on antique blocks exceeding $1 million per kilogram.

Global Tea Production

Large-scale commercial tea production uses two forms of Camellia sinensis: small-leafed sinensis and broad-leafed assamica, which are prevalent in China and Assam, respectively. Sinensis is the variety most often used for green tea, and assamica for black tea. There are wild relatives to tea in the form of 12 similar species of Camellia and 6 recognized varieties. In Yunnan, 11 of these wild tea species are harvested from forest for small-scale trade, some of which enters international markets. Within its natural range, tea grows as an understory plant in forests at altitudes between 328 and 7,218 meters.

Large-scale tea production was initially based in China and India, within the natural distribution of Camellia sinensis as a wild plant. It then extended to Japan, Turkey, and Sri Lanka. Turkish tea, with its distinctive red hue, is grown in the Black Sea region and is not a significant export. Rather, it supplies the large demand for tea in Turkey. Introduced to Kenya in 1903, tea rapidly became a notable export crop, and Kenya grew to be the biggest supplier of tea to global markets. More recently, Rwandan tea has gained acclaim and features in tea blends sold by international companies. Ecuadorian tea is consumed within the country. In the Azores, the interest of visiting tourists supports the continued production of tea, but it is not a significant export. Tea grown in Cornwall, England, is added in small amounts to a blend of tea sourced predominantly from the major tea exporting countries. Within the U.S., there is small-scale production of tea in New Jersey, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, and Washington State. Because ambient temperature and humidity influence the speed at which oxidation proceeds, this stage of processing defies set times and relies on expertise in situ.

Tea as an Ingredient

Dried tea has a long shelf life, an asset for managing stocks to allow year-round production of spirits. While dried tea can wait, once immersed in liquid, the length of infusion and the type of liquid used shape the extracted flavor. Extracting the flavor of tea is rapid when using hot water and slow when using cold water. One sees the growing recognition of the influence of temperature on taste in the availability of kettles with specific settings for different types of tea. White and green tea are best made with water around 175°F. Boiling hot water is better suited to releasing the flavor of black tea. Cold brewing releases less caffeine and tannin than making tea with hot water. Similarly, using alcohol as a solvent instead of water creates a different flavor profile.

While tea can be a stand-alone ingredient, there are several long-standing successful combinations of tea with other ingredients. However, it should be noted that not all ingredients added to tea are for flavor. Some additions serve aesthetic purposes, like dried cornflower adding bright blue flecks of color to loose leaf tea. Others, such as Dendrobium fimbriatum added to green tea, connect with cultural use of this orchid’s canes in traditional Chinese medicine.

Combined with sugar, rose can tend toward a sickly flavor. In rose pouchong, tea provides a sophisticated foil to the perfume of dried rose petals. Toasted rice in genmaicha tea moderates green tea’s bitterness. Earl Grey lifts the aromatic profile of tea by including the citrus bergamot. Lapsang souchong tea is desirably smoky and echoes peat smoke in peated whiskeys. Chai, as served in India, comprises a sturdy combination of boiled tea, heated milk, and plenty of sugar, with an aromatic scaffolding of spice blends, usually including cardamom, cinnamon, clove, and pepper. British-style tea served with a dash of milk and Taiwanese bubble tea served milky and cold both take advantage of the lactose in milk bonding with the tannins in tea and thereby moderating the beverage’s astringency. There is certainly versatility in the partnership of tea with other ingredients, from the simple lightness of rose pouchong and lapsang souchong to the sturdiness of strong, milky teas.

In the distillery, tea can be infused and then distilled, or added after distillation. Incorporating it post-distillation allows its contribution to color and mouthfeel to persist in the final product. Different types of tea — white, green, oolong, black, and pu-erh — yield different colors. Pu-erh infuses to an unusual red-toned color, while Rwandan tea is bright and coppery, changing to golden when milk is added.

While there is obvious appeal in using a local supplier, the endurance of traditional tea growing areas and the ability to supply large volumes of ingredients is more secure for products intended to be permanent, year-round additions to a portfolio. Sensory analysis to take note of the influence of temperature and length of infusion is vital for developing a distilled spirit or liqueur using tea, as small changes in these parameters have notable effects.

One way of distinguishing a liqueur is adding an unexpected contrast to sweetness. In De Kuyper Lapsang Souchong Liqueur, infused and distilled lapsang souchong tea provides more complexity than might be expected from one ingredient. This is because lapsang souchong is a type of black tea that is dried over burning pine wood and takes on smoky and resinous flavors.

Absolut Wild Tea Vodka eschewed sweetness and tempered the floral note of elderflower with oolong tea. As a perfumed vodka, it was better used in combination with other ingredients in cocktails than as a stand-alone drink. For many consumers and distillers, the appeal of tea as an ingredient includes the slight astringency and visible coloration of tannins retained in the end product when tea leaves are infused after distillation.

Gin and gin-based liqueurs have also incorporated tea in their botanicals. Heston Blumenthal Earl Grey gin extends the classic citrus note added to gins with lemon peel by using the bergamot-infused flavor of Earl Grey tea. This flavor pairing was repeated in Heston Blumenthal’s Fruit Cup. Sipsmith’s London Cup successfully takes the classic “summer cup,” usually dominated by fruitiness, into sophisticated territory by focusing on aromatics. Gin infused with tea acts as a foil to rose, lemon verbena, and borage.

Preferred tea brands are a frequent item in luggage so that when people travel they can have their familiar cup of tea. Visiting Yorkshire, for instance, it would be unusual if you didn’t encounter Yorkshire Tea. While Yorkshire Tea is based in Yorkshire, its black tea is a blend of tea sourced from several countries. This is worth remembering when working with tea at the distillery. You might be able to tap into a small-scale local supply, but skillfully blended teas can also inspire great loyalty. When using tea as an ingredient, remember that terroir shapes its taste, and blending tea from different sources can create a unique signature flavor.