The Kingdom of Sardinia, which linked wine-growing soils and mountains bearing lush herbs was responsible for the genesis of vermouth. This seafaring kingdom was split between the fierce, rugged island of Sardinia, green-clad slopes of the Alps around Turin, and Savoy, an area in what is now part of France. While the Kingdom of Sardinia grew, discarded Savoy and eventually was subsumed into Italy, the taste of vermouth still lingers.

Vermouth recently went through a dowdy phase: languishing in cupboards with opened bottles gathered dust. Aalthough passable in cocktails, they were not a drink to be savored. Salvation came in assorted forms. In the height of the financial crisis in Spain, vermouth served over ice was far cheaper than a cocktail and provided a complex flavor to be enjoyed at leisure.

Vermouth has attracted the attention of millenial cocktail aficionados and, with that, the efforts of a new generation of makers, who have found a niche in using wine as a base for creative interpretation. Consumers have also learned how to treat vermouth nicely — using a vacuum cork and keeping it in the fridge to slow oxidization once the bottle is opened. Bars such as Amor y Amargo in New York and Mele e Pere in London serve house-made vermouths. Most customers sipping a house-made vermouth at a bar won’t go home and make their own, but they are primed to buy vermouth to enjoy at home. Bars’ serving of vermouths as an aperitif, and not just in cocktails, has increased the market by presenting them as a drink that is easily revisited at home.

Technical definitions of vermouth parse in terms of alcohol content and color (for example, distinguishing between red or white vermouth). However, distillers can leave classification to the consumers by using clear bottles and the same labels, as Lillet does for its rouge, rosé and blanc. Vermouths occupy a liminal space: fortified to be stronger than wine but weaker than spirits, and aromatized to carry herbal flavors that are tempered by a sweetness that is less cloying than liqueurs. For the producer, it is an opportunity to embrace terroir and it is neither restricted to selection of grape varietals nor where they are grown.

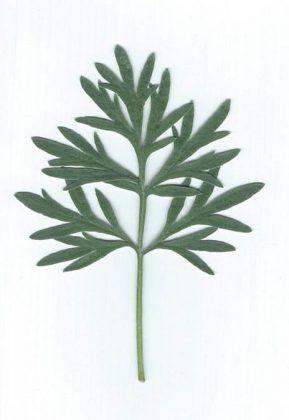

Vermouth derives its name from the German wermut and the French vermout, which translate to wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). To meet the European definition of vermouth, at least one of the many species of wormwood (Artemisia spp.) is required to be included in uthe recipe. In ancient Greek and Roman times, infusing wine with herbs was a common way of extracting medicinal properties of plants. Wormwood was valued as a vermifuge. Aromatized wines such as vermouth crossed from medicinal use to drinks consumed for pleasure. Aromatizing wine with wormwood is not sufficient for making vermouth — it must also be fortified and additional flavors should be included. In the USA, many vermouths are made without wormwood, not least because FDA legislation stipulates that the finished beverage must be free of thujone, .a compound considered by the authorities to be psychoactive and toxic in large doses. Thujone is present in snotable amounts in wormwood, as well as other bittering agents such as yarrow (Achillea millefolium), a native U.S. species, and tansy (Tanacetum vulgare), an introduced species. Wormwood, yarrow and tansy all provide aromatic bitter flavors.

Yellow gentian (Gentiana lutea) is a common sight in the Alps and used in many vermouths as the bittering agent. Its roots are the part used for flavor; sometimes they are sold under the pharmaceutical name Gentianae radix. Although a mountain plant, it is amenable to cultivation and will grow in temperate areas of the USA.

Quinine is a familiar bittering agent that is extracted from the bark of several species of cinchona. These tropical trees provided medicinal bark that became known as “priest bark” because it was found to combat malaria, which afflicted so many priests travelling to the tropics during the colonial era. Not only used in tonic water, it also is featured in several vermouths, particularly red vermouths, that would otherwise be oppressively sweet.

In addition to bitterness balancing sweetness, vermouths are characterized by their blend of aromatic flavors. Many members of the mint family that are native to the Mediterranean region are used for this. Hyssop (Hyssopus officinalis) is a shrubby plant whose leafy, flowering tips have a minty-resinous taste used in Chartreuse as well as vermouth. Oregano (Origanum vulgare) offers a softer aroma. These Mediterranean plants are widely cultivated in the USA. Plants native to the USA that provide similar flavor profiles include black sage (Salvia mellifera) that can be abundant in California, and bee balm (Monarda didyma), which grows in the eastern USA.

Chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) is a botanical that can be underwhelming when accessed via long supply routes. On the other hand, its flowers can be incredibly fruity and honeyed, adding a sweet apple flavor, when they are grown in a hot, dry climate, well dried and stored in vacuum-sealed packaging. For distilleries with space to grow a patch of chamomile, it is well worth the minimal effort. It needs to be kept weed-free, but better treated a little mean with hardly any watering, as the flowers produce much more intense aroma when grown in dry conditions that are similar to early summer in the Mediterranean.

Another fruity element that works well in vermouth is rhubarb (Rheum rhabarbarum). Apart from use in vermouth it shares another feature with wormwood and cinchona — it was once a very popular medicinal plant. Rhubarb featured in Chinese medicine for thousands of years, and in 19th-century Britain it was one of the most frequently used medicinal plants. Distillers are better off using the stalks for the fruity flavor than the roots that were deployed for their purgative effect. Rose hips, the fruits of roses such as Japanese rose (Rosa rugosa), are another fruity botanical, which can be easily dried for a year-round supply and production schedule.

Spices are also used to enliven vermouths. Most spices in trade originate from the Old World of Europe, Africa and Asia. Only a few spices originate from the New World (i.e., the Americas), one of which is allspice (Pimenta dioica), native to Central America and the Caribbean. Its name is entirely descriptive of its flavor — allspice tastes like a blend of spices, making it an excellent botanical that provides more complexity than most individual plants. An excellent spicy plant native to North America whose name is also an aptronym is spicebush (Lindera benzoin). Like allspice, its berries have a warm, spicy taste.

Vermouth makers can create batches in response to local gluts, which can be a cost-effective and environmentally conscious method of production. This foregoes a consistent taste from batch to batch, but contemporary consumers are increasingly happy to make purchases trusting the skill and taste buds of producers to create something they will like. Vermouth can also be made in response to the terroir of a producer. Allowing landscape to dictate the plants that naturally grow wild, and the flavors of plants cultivated, casts vermouth producers as curators of local flavor, an excellent way of capturing a taste of place in a bottle.